FiveThirtyEight, Nate Silver’s math blog, published an article by Travis Sawchik yesterday under the headline “Do We Even Need Minor League Baseball?” In the piece, Sawchik argues that advancements in technology and data analysis have made both the discernment of genuine major-league baseball talent and the off-field development of baseball skills easier and more efficient than ever. As a result, it’s no longer clear that baseball prospects need to spend years playing their way up through the levels of a tiered affiliate farm system in order to thrive as major-leaguers. Therefore, it’s no longer clear that big-league ballclubs need bother maintaining those farm systems.

I see some problems with this argument! I’m just going to list a few of those, here, in some order.

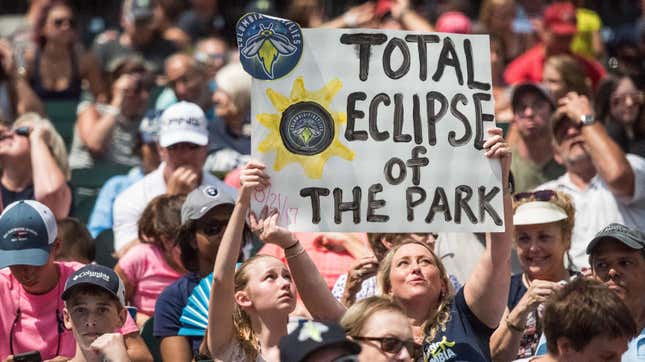

1. Let’s start with the headline. As Sawchik notes in his article, total minor-league attendance declined by 1.38 million people last season, the first time it has declined in 14 years. As Sawchik fails to note in his article, 40.5 million people still nevertheless attended minor-league baseball games last season. Minor-league baseball remains quite popular! I do not think any reasonable person would call for the elimination of, say, the National Hockey League, if its paid attendance dropped by a little over three percent next season. And so the question, as always, is: “Who the fuck is ‘we’?”

2. This gets directly at a much larger problem with the article. Who exactly is minor-league baseball for? The 30 big-league clubs use it as a developmental system for their young prospects, of course. Is the fact that tens of millions of people choose to buy tickets to watch affordable baseball games incidental to that, or is it the other way around? Getting rid of minor-league baseball isn’t going to lower ticket prices at big-league stadiums, or move those stadiums closer to the cities and towns in which minor league teams play, or magically add tens of millions of seats to the big-league venues where minor-league fans could now enjoy Major League Baseball instead.

3. One need not perform sophisticated analysis to see that, both for the health of the broader sport of baseball and for the specific individual big-league clubs, it is in fact good for there to be lots of easy, affordable, family-friendly ways for people to consume the sport in person and form rooting attachments to the people who play it. One of baseball’s weaknesses is that it lacks the kind of transcendent individual stars that could make a big impression on a casual, national audience, but one of baseball’s biggest and most distinctive strengths is that there are millions and millions of people who just like going to watch a ballgame without too much regard for who in particular is playing in it. There happen to be enough broadly good baseball players out there to fill out the rosters of over 250 ticket-selling baseball teams across the country, and those people can—and will, and largely do—pay to watch them play. Almost all of those players will never play in the majors, but every now and then spectators will get to watch a green young talent figuring things out on his way to the big-league club. At least some of those spectators will stick to that kid for that reason, to the point where they’ll sit through a three-hour baseball broadcast or purchase expensive tickets to an occasional big-league game to see him play. That’s good, and redounds to the benefit of both those players and the organizations that employ them in a way that cannot be replicated by having the player swing a bat inside a specially outfitted shipping crate with a bunch of cameras trained on him.

4. More importantly, and perhaps only orthogonally related, those fans enjoy going to and watching minor-league baseball games, and professional baseball is a spectator sport that exists so that people can enjoy watching it. We’ll come back to this in a second.

5. Here is a passage:

MLB’s approach to the minor leagues is ripe for change in part because of how much data can be collected off the field these days. Independent hitting instructor Doug Latta tells his clients that they “don’t need much space to get better,” as improving via reps, video analysis, and ball-tracking tech lessens the need for a player to play in regulation games. Latta worked with Marlon Byrd, Justin Turner, and Hunter Pence in various storage-like facilities just before they changed their approach at the plate and improved their performance. Cody Bellinger was already a good major league player but became great this season after he changed his swing in similar modest spaces last winter. While batting cages have existed since [Branch] Rickey invented them, they’ve never been the feedback machines they are today when outfitted with ball-, bat- and body-tracking tech.

On the pitching side, it’s perhaps even easier to gain skills. Adam Ottavino designed a new cutter last winter in a vacant Manhattan storefront that he outfitted with baseball’s cutting-edge tech. The Los Angeles Dodgers held several low-value minor league pitchers back from minor league games in 2016, giving them something of an extended spring training at their complex to see if they could improve throwing velocity. Dodgers pitchers Corey Copping and Andrew Istler learned how to throw harder and subsequently became trade chips last summer.

The argument here is that, vis-a-vis their development as players, it doesn’t actually matter whether professional baseball players play games of baseball. In the broadest, most existential sense, this is definitely true! It also doesn’t matter whether they eat food or take breaths. As an intermittent depression enthusiast, I find much to like in this perspective. But also, baseball games are the part of a professional baseball player’s job that people will pay to watch, just in that the demand, by fans, for professional baseball, is a demand for baseball games to watch. The reason to have a baseball game in a stadium, in front of thousands of paying spectators, is not so that a guy with a camera can collect data about the pitch grips and swing trajectories of the people playing in it. The reason to have a baseball game in a stadium in front of thousands of paying spectators is so that those thousands of paying spectators will not do something else with those hours of the day, and with the money they might spend on baseball tickets if there is a baseball game to watch.

6. “In the NBA and NFL, top amateur players get thrown straight into the fray against top professionals. In baseball, top prospects spend years against lesser competition. How do you improve against inferior players?” That’s from the 21st paragraph of Sawchik’s very long article. It’s just a flat-out dishonest framing of the difference between the respective sports. Incoming NBA and NFL rookies only qualify as “amateur players” because of cartel rules that prevent them from earning a living during the (unpaid) years they spend improving their skills against inferior players. In every meaningful respect except the lack of an aboveboard salary, the NFL’s and NBA’s top prospects spend formative developmental years in minor leagues playing against lesser competition. It’s just that those sports’ draft eligibility rules prop up the NCAA as their sports’ developmental minor league.

7. Which is to say, the key word in that quoted passage is “amateur.” The real question being examined in Sawchik’s article is not whether smart data analytics and blossoming technology have given Major League Baseball clubs an opportunity to advance beyond the developmental benefits of having affiliated minor-league clubs. The real question being examined is whether those clubs can sell smart data analytics and blossoming technology as the pretext for drastically shrinking the number of people who get paid to play baseball. Or, more to the point, the question is whether fans of the sport of baseball can be convinced to celebrate and congratulate large, rich, powerful baseball companies for deciding to disinvest from the actual sport of baseball—literally providing less baseball for fans of baseball to watch and enjoy—in the name of disruptive, technologized efficiency.

8. Here’s where the NBA and NFL actually do provide handy and illuminating test cases! In those leagues, this gambit already has broadly succeeded. You know it as “The Process,” the marketing scheme that relocates fan identification from the players who play the sport to the front-office managers who acquire and exchange those players; that treats the actual physical sport, and the attendant obligation to stage competent and entertaining displays of that sport for viewing fans on a regularly scheduled basis, as not only secondary to but a vulgar distraction from a sports franchise’s true mission, which is the nimble, data- and technology-juiced optimization of various abstract assets. The question is: Will a certain cross-section of fans and wised-up media types not only tolerate but exult in—like, build an entire identity around exulting in—replacing the pleasurable experience of watching competitive sports with a vague promise that the sports will be great at some unidentified future point, underwritten by grainy tweeted videos of some guy swinging a bat inside a garage? And here the answer is: Definitely yes!

9. If it seems a strange coincidence to you that the idea of MLB clubs drastically slashing the number of affiliated minor-league teams—and thus the number of minor-league jobs—has come up, portrayed as the analytics-and-technology-aligned way of the future, right on the heels of a surge in attention to how badly those clubs treat (and pay) their minor-league ballplayers, well. Clearly you are some kind of insane conspiracy theorist!

10. No but seriously: This seems more and more like the dystopian endpoint of Processism, and more broadly of the analytics revolution in sports. The first part of that revolution involved advanced metrics and abstractions coming out of theoretical space and being brought to bear directly upon the on-field tactics and personnel moves of sports teams. But the second part, which began with the advent of “The Process,” increasingly involves withdrawing sports from physical space and rendering it purely theoretical, ever more fully the domain of front-office executives. This reduces the people who play the sport, as well as the actual events of the sport as played by those people, to noisy, messy free radicals that can only serve to fuck up the real game, which happens in virtual space, or at least in some pasty executive asshole’s office, on a computer running a number of proprietary algorithms or whatever.

11. Where does that leave you, if you’re just somebody who likes going to a ballpark and watching a baseball game? If you just, y’know, like the actual sport of baseball, and enjoy watching it played well by players who, even if they are not quite MLB-quality, are quite good at playing it? If you’re more than happy to pay the modest price of a minor-league ticket and take the tradeoff in quality in exchange for not having to travel more than an hour to get to a seat at a major-league stadium? If you’re watching the game as a game and not as an abstract validation of some front-office philosophies that you read about online? Increasingly, the ascendant conception of what sports is and what it’s for views a person like you as some kind of cave oaf, a thick-skulled doofus who doesn’t really get what this is about and has nothing especially relevant to say about it.

12. So, back to the above. Who is any of this for? It isn’t for anybody. It’s for itself. It’s just a machine that runs. Like all others, if you pull back far enough, it just makes sand. For now, though, it makes it at least in part by staging baseball games at various levels for people to watch and enjoy, and on the whole that’s better than what’s to come.