Social perception bias is best defined as the all-too-human tendency to assume that everyone else holds the same opinions and values as we do. That bias might, for instance, lead us to over- or under-estimate the size and influence of an opposing group. It tends to be especially pronounced when it comes to contentious polarizing issues like race, gun control, abortion, or national elections.

Researchers have long attributed this and other well-known cognitive biases to innate flaws in individual human thought processes. But according to a paper published last year in Nature Human Behaviour, social perception bias might best be viewed as an emergent property of our social networks. This research, in turn, could lead to effective strategies to counter that bias by diversifying social networks.

“There’s a fundamental question about how people perceive their environment in an unequal society,” said co-author Eun Lee, a network scientist based at the University of North Carolina. Her interest in the topic was piqued in the wake of the 2016 US election and the mass protests and subsequent impeachment of the president in her native South Korea that same year. "Both sides had been separated into two groups by each issue," Lee wrote in an accompanying Nature essay. "At the time, I was studying topics related to opinion dynamics models and wondered what was leading these collective segregation behaviors. It seemed the tendency of hearing from like-minded people trapped them in their own opinions."

“There’s a fundamental question about how people perceive their environment in an unequal society.”

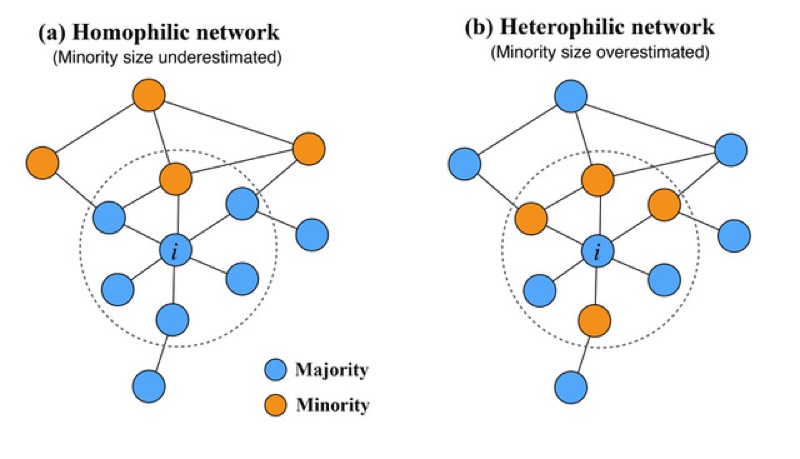

Lee had made the acquaintance of co-author Fariba Karimi of GESIS, in Germany, earlier that year at the Santa Fe Institute in New Mexico. The two decided to collaborate on a study of the effect of "homophily"—people's tendency to hang out with those who are similar to them (think "birds of a feather flock together")—on people's perceptions using network models. They came up with a generic binary model dividing individual nodes into two groups: Democrat or Republican, smoking or non-smoking, male or female, immigrants or nonimmigrants, for example.

The model treated people as individual nodes in a network, with no consideration of human cognitive processes. The emergence of perception biases depended solely on the relative sizes of the majority and minority groups, and the extent to which like nodes connected to other like nodes. To test the predictions of their model, they collaborated with co-author Mirta Galesic, who leads the research group on human social dynamics at SFI. The team conducted a survey of 300 participants based in Germany, the US, and South Korea, asking about perceptions of specific minority-associated attributes.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...