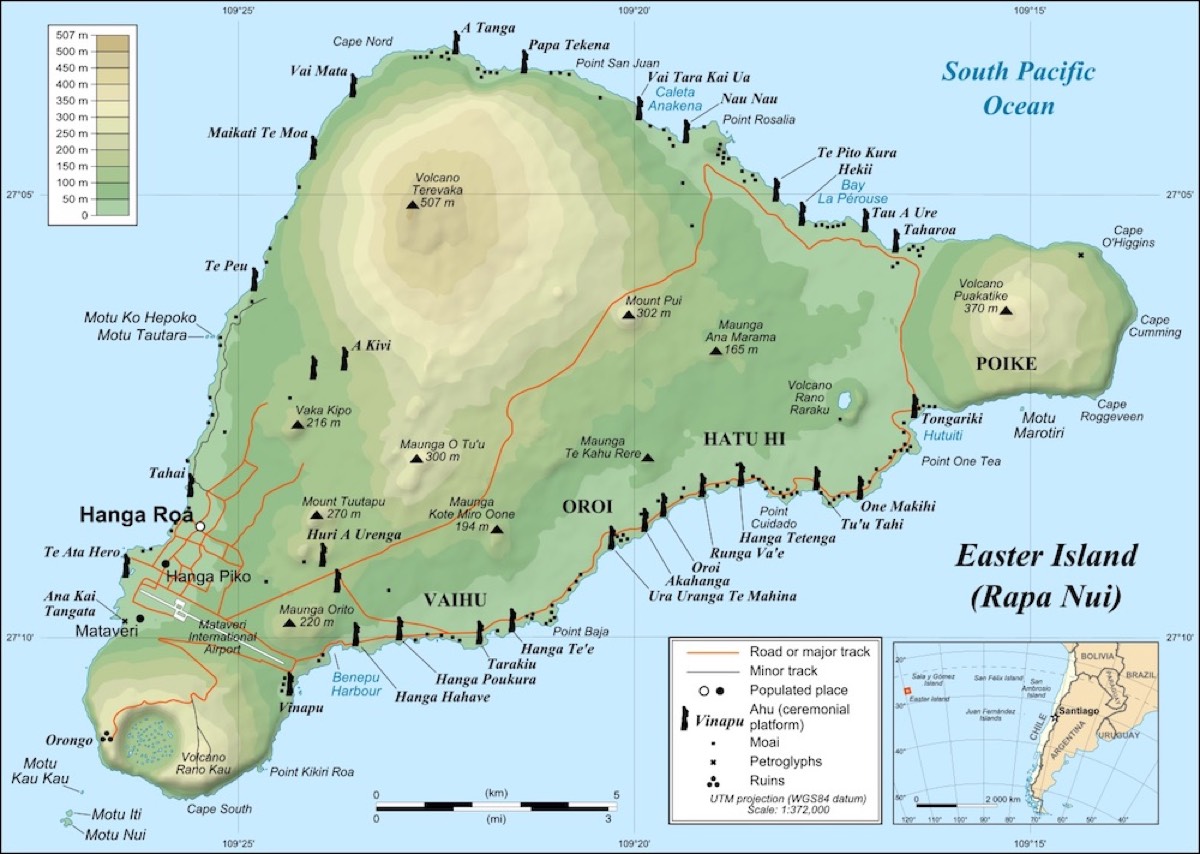

In his bestselling 2005 book Collapse, Jared Diamond offered the societal collapse of Easter Island (aka Rapa Nui), around 1600, as a cautionary tale. Diamond essentially argued that the destruction of the island's ecological environment triggered a downward spiral of internal warfare, population decline, and cannibalism, resulting in an eventual breakdown of social and political structures. It's a narrative that is now being challenged by a team of researchers who have been studying the island's archaeology and cultural history for many years now.

In a new paper published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, the researchers offer intriguing evidence that suggests the people of Rapa Nui continued to thrive well after 1600. The authors suggest this warrants a rethinking of the popular narrative that the island was destitute when Europeans arrived in 1722.

"The degree to which their cultural heritage was passed on—and is still present today through language, arts, and cultural practices—is quite notable and impressive," co-author Robert DiNapoli, a doctoral student in anthropology at the University of Oregon, told Sapiens. "This degree of resilience has been overlooked due to the collapse narrative and deserves recognition."

Easter Island is famous for its giant monumental statues, called moai, built by early inhabitants some 800 years ago. Scholars have puzzled over the moai on Easter Island for decades, pondering their cultural significance, as well as how a Stone Age culture managed to carve and transport statues weighing as much as 92 tons. The moai were typically mounted on platforms called ahu.

Back in 2012, Carl Lipo of Binghamton University and his colleague, Terry Hunt of the University of Arizona, showed that you could transport a 10-foot, 5-ton moai a few hundred yards with just 18 people and three strong ropes by employing a rocking motion. In 2018, Lipo proposed an intriguing hypothesis for how the islanders placed red hats on top of some moai; those can weigh up to 13 tons. He suggested the inhabitants used ropes to roll the hats up a ramp. And as we reported last year, Lipo and his team concluded (based on quantitative spatial modeling) that the islanders likely chose the statues' locations based on the availability of fresh water sources, per their 2019 paper in PLOS One.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...