While most plastics have generally been produced from petroleum, that’s not an inherent requirement. Chemistry is chemistry, and it’s possible to grow many of the hydrocarbons we need. But crops are the things we are best at growing, and plastics made from crops can have problems. They tend to cost more, and unless we're willing to accept impacts on our ability to grow food, pathways to bioplastics have to be pretty clever about their starting materials.

A new study led by Durham University’s Long Jiang, Abigail Gonzalez-Diaz, and Janie Ling-Chin lays out a pathway to making plastic bottles from waste organic material and CO2 captured from power plants. A thorough analysis of the economics shows this process could even be cost competitive for making things like plastic bottles.

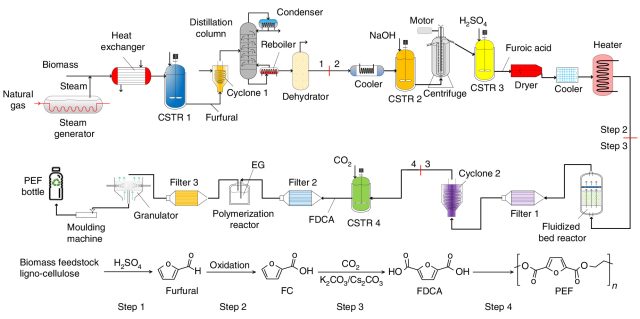

The process could start with something like the leftover plant material from sugarcane pressing. After a few reaction steps, which include the addition of some captured CO2 and some ethylene glycol produced from corn plants, you’d end up with a plastic polymer called polyethylene furandicarboxylate—otherwise known as PEF. Functionally, it’s similar to the PET plastic used for water and soda bottles, denoted by the number 1 recycling symbol.

Every step in the process has been at least demonstrated before, and some are quite common, so the paper doesn’t spend much space on the chemistry. Instead, the researchers engage in life cycle analysis of the manufacturing process to estimate exactly how this method of making PEF would stack up with the competition.

That includes greenhouse gas emissions. Compared to the manufacturing of PET, their PEF process emits about one-third less greenhouse gas. This assumes that the heat and electricity required for manufacturing is coming from natural gas rather than renewable alternatives. But the process itself includes the consumption of some captured CO2, offsetting some emissions.

Interestingly, other proposed methods for making PEF are actually associated with lower emissions than that. However, those methods rely on using food sugars rather than leftover plant material—something the researchers wanted to avoid.

Sustainability benefits aside, the cost of this process seems to put it at a disadvantage on the surface. The study estimates we could make PEF for about $2,400 per ton, while conventional PET is produced for $1,800 per ton. That would require PEF to fetch a premium on the market to be profitable as a business venture.

But there is one additional thing to consider: it might well be that you could make a PEF bottle with 25-percent less plastic. While PEF and PET have similar enough properties that they fit the same niche, PEF is a little sturdier. “As such, the PEF production cost per bottle could be the same as or lower than that of PET,” the researchers write.

So it’s at least possible that an approach like this would be commercially viable—especially if some cost savings were found along the way. Then you might see sugarcane-derived bottles holding your fizzy sugar fix.

Nature Sustainability, 2020. DOI: 10.1038/s41893-020-0549-y (About DOIs).

reader comments

97