What It Will Take to Avoid a Global Food Shortage

A year before the Covid-19 pandemic caused havoc in the world’s food supply, venture capitalists plunged $125 million into a company that breeds mealworms. Ynsect in northern France, which turns the grubs into animal feed and fertilizer, needed cash to build the world’s largest insect farm, a robot-staffed plant that would raise its output 50-fold.

It’s one of thousands of food and agriculture companies that worked largely in obscurity until the coronavirus overturned the global food supply chain. With supermarket shelves stripped by panic buying, livestock destroyed because meat packing plants had shut, and quarantined consumers battling to get deliveries, food security, self-sufficiency and urban farming suddenly became household words and governments started to reexamine how their countries are fed.

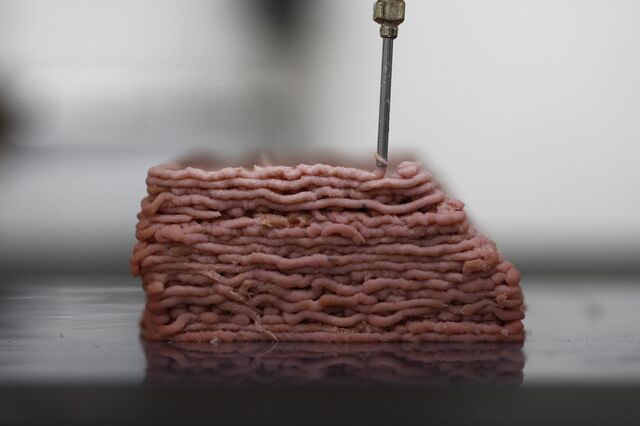

Photographer: Akos Stiller/Bloomberg

Photographer: Angel Garcia/Bloomberg

Photographer: Prashanth Vishwanathan/Bloomberg

Photographer: Carla Gottgens/Bloomberg

Sound is off

With seed-to-table food cycles taking months for major crops, the full impact of the virus has yet to be felt, but the evidence so far shows that countries with a wide variety of suppliers, both domestic and foreign, are best placed to weather the disruption. New technologies to boost output, local production of high-value crops and changes in diet all have a part to play, but ultimately, the key to robust food supply for everyone is more global trade, not less.

“Growing your own food is not a recipe for food security, said Alan Matthews, professor emeritus of European agriculture policy at Trinity College Dublin. “You need to be able to diversify and international trade is a way of diversifying and therefore keeping us food secure.”

Less Wealth, Less Food

Lower income populations suffer more from food insecurity

Note: Based on Food Insecurity Experience Scale which measures limits to food access due to lack of resources.

Source: FAO

That said, increased trade probably won’t be enough to feed us all as the global population grows and people in developing countries eat more. Shrinking farmland, climate change, water scarcity, overfishing and pollution have all put the world’s nutrition supply under strain. An intricate global network of growers, processors, shippers and retailers has arisen to address the imbalances. When the pandemic spread, it demonstrated many of the weaknesses in that chain.

And it’s going to get worse.

By 2050, the global population will be nudging 10 billion people, each of whom will eat on average 12% more than they did in 2000, including about twice as much meat and poultry, according to estimates from the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization. That would mean food consumption rising by 70% in the first half of this century.

Meeting the challenge will require three major changes: increased global trade; more efficient and varied production; and a change of diet.

The biggest obstacle standing in the way of the first of these is a growing political shift toward protectionism that has been made worse by the coronavirus. Administrations around the world reacted to panic buying and logistics disruptions by threatening to curb food exports or promising to increase self-sufficiency.

“What this pandemic reveals is that there are goods and services that must be placed outside the laws of the market,” French President Emmanuel Macron said in March. “To delegate our food, our protection, our care-taking ability, our quality of life, in the end, to others is madness.”

▼

Ynsect is one of those looking for ways to make farming more efficient and at the same time reduce the need to source some agricultural inputs and crops externally. It’s one of dozens of startups in Europe, Africa and elsewhere that show insects can be an economic raw material for farms that can be set up almost anywhere. “The coronavirus will show even more the need for local production in Europe, and protein sovereignty in Europe,” said Antoine Hubert, chief executive officer of Ynsect and president of the International Platform of Insects for Food and Feed.

Using more efficient ways to raise output could help some developing nations dramatically increase supply, creating new sources for countries buying in the world market.

“India has one of the largest areas of arable land and different climatic conditions, suitable for different crops,” said Mithun Chand, executive director at Kaveri Seed Co. in Hyderabad. He said improvements such as adapting seeds to a particular environment could increase productivity by as much as five-fold. “India has the scope and potential to produce for the entire world.”

Arable Land

Projected figures for 2030 based on 2015 data

Source: FAO

It isn’t just developing nations that can improve output and diversity of crops. Some of the most dramatic changes to the 12,000-year-old agriculture industry are being tested by technology startups around the world that are coming up with better ways to grow, water, fertilize and harvest crops, and feed and rear animals – or replace them.

Researchers at Wageningen University in the Netherlands developed pepper-picking robot Sweeper, while in Israel Beewise has solar-powered, automated bee hives to pollinate plants, and Skyx deploys drone swarms to spray crops. Many of these systems will take time to have a major impact on food output. Often they are too expensive for farmers, especially in poor countries. Even in wealthier nations, farms are geared mostly to manually operated machinery.

“You’ve got to redesign how farms work if you want to put robots onto them,” said Tim Lang, professor of food policy at London’s City University and author of ‘Feeding Britain’. “It’s 15 years away.”

The coronavirus has given a new impetus to automation, especially for labor-intensive processes such as harvesting and processing.

“Large companies that are controlling the materials that go into the production of food have typically been lingering to see how things shake out with new technology,” said Shmuel Rausnitz, an agrifood-tech sector analyst at Israel’s Start-Up Nation Central. Now, “it isn’t just a nice-to-have, it is a must have,” said Rausnitz.

Raising output by putting more land under the plow is becoming increasingly contentious because of deforestation and habitat loss. Brazil has more than doubled its soybean output in the past decade, partly by expanding into the Cerrado, one of the last big tropical savannas.

Vanishing Forests

Predicted land-use change 2010-2050 based on continuation of current trend

Sources: PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency, United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification

A better alternative may be to reclaim fields that have been lost to desertification or misuse. At least a third of the world’s arable land has been degraded to some extent because of poor management, urbanization or climate change, affecting the lives of 2 billion people, according to the FAO. UN scientists estimate some 900 million hectares could be restored by adopting existing techniques such as the sustainable use of fertilizer and irrigation.

China, which depleted millions of acres during its industrial ascent, is trying to reverse the attrition by increasing the amount of high-quality farmland – capable of growing grains despite flooding or drought -- by 25%. “China has to safeguard its farmland to ensure enough area to grow cereals,” said Fang Yan, a researcher at Tsinghua University’s China Institute for Rural Studies who advises the government on food security.

But for producers like India to be big international suppliers requires a change in the politics of the highly controlled global food trade, which is characterized by import quotas, subsidies, taxes and other interventions, often to protect rural communities that make up a large proportion of the electorate.

Some of those controls are breaking down. India is working to free food distribution and pricing from government control and new rules in China will allow millions of smallholders to lease their land to bigger, mechanized farms that can increase productivity.

“Covid-19 has shed light on the vulnerabilities of food production and supply chain and in that it will drive some changes in the agribusiness space, such as a renewed emphasis on food security,” said Aurelia Britsch, head of commodities research at Fitch Solutions. The virus could give a boost to automation, local-origin products, reduction in food waste and alternative proteins, she said.

One message from Covid-19 is the weaknesses in distribution. Even without a global virus, the supply chain suffers huge losses overall. The world grows enough food to feed well over 9 billion people, yet we waste or lose one third of it through pests, harvesting, processing, storage and transportation, or by simply throwing away uneaten dinners.

Nor is food distributed evenly. More than 2 billion people are overweight or obese, including 340 million children, while more than 800 million are underweight or undernourished, according to the World Health Organization. Global wheat stockpiles are expected to hit a record this year with bumper harvests, but the World Food Programme estimates 42 million people could need food aid just in the 12 Southern African countries where the UN agency operates.

An estimated $12 billion of major agricultural crops are lost during harvesting and post-harvest operations in India, far more than the losses due to poor storage or inadequate transportation, according to a 2015 study by the Ministry of Food Processing Industries.

Total Food Waste and Loss in 2050

Note: Refers to the sum of the food lost and wasted in production, transportation and distribution. Also includes household food waste.

Source: Millennium Institute

The pandemic brought that inequality to the doorstep of rich nations. With food supplies disrupted in the U.S. and millions out of work, a USDA survey in April showed that more than 17% of mothers with young children in the country said their children weren’t getting enough to eat because they couldn’t afford the food.

Part of the onus to get people to eat less – and more healthily -- is down to governments, for example by taxing sugared drinks and reducing subsidies for input-heavy farming such as cattle. Here too, innovation plays a part, with plant-based meat startups Impossible Foods Inc. and Beyond Meat Inc. pushing big meat companies like Tyson Foods Inc. and Smithfield Foods Inc. to come up with their own alternatives.

Still, the biggest food debate fueled by the pandemic is over local production. The arguments for it aren’t new, with advocates touting a reduced carbon footprint, freshness and greater control of quality. With many national interests now out-gunning free trade, some governments are becoming stronger advocates of food sovereignty.

Russian Deputy Prime Minister Viktoria Abramchenko said the virus showed Russia’s need to boost domestic production of seeds, pedigree livestock, veterinary medicines and crop-protection chemicals. Russia imported about $30 billion of agricultural products last year, including supplies of Chinese vegetables to its far eastern regions. “Prices for cucumbers and tomatoes in the far east increased sharply because China was closed,” Abranchenko said, promising to build more greenhouses.

Local and regional production does have a part to play in food security, especially when it uses innovation to provide a cheaper alternative to imports.

Singapore and the United Arab Emirates both import around 90% of their food and have invested significantly in local production using technologies such as solar power, hydroponics and indoor farming. Both have concentrated on high-value fresh produce such as leafy vegetables and eggs.

“We’re producing year-round, pesticide-free produce for under $1 a kilogram -- 25% to 60% cheaper than comparable quality imports,” said Sky Kurtz, founder of three-year-old PureHarvest, which grows tomatoes in desert greenhouses in the U.A.E. and recently raised $100 million to expand output.

Photographer: Lauryn Ishak/Bloomberg

Photographer: Corinna Kern/Bloomberg

Photographer: Christopher Pike/Bloomberg

Sound is off

The Singapore Food Agency, set up last year to oversee food safety and security, aims to increase local production to 30% by 2030, from less than 10%. The island is investing in everything from vertical farms to hydroponics and plans to build a sustainable suburb called Tengah that would include a community farm to help feed the estate’s 42,000 households. Local start-up Citiponics has a commercial vertical farm on top of a multi-story car park growing a special variety of lettuce suited to the climate.

Local production, however, isn’t the answer for many types of food. Climate, topography and access to labor are among the factors that combined to make Brazil a major coffee producer, the U.S. Midwest an abundant source of grain and Indonesia the biggest exporter of palm oil. Roughly 17% of the world’s population relies almost entirely on international trade for food, according to a report by the World Trade Organization in April. That proportion could rise to 50% by 2050, the report said, citing an estimate by the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research.

Still, increasing food production alone won’t ensure food security worldwide without dismantling barriers to trade.

“Just as Covid-19 has hit some of the most vulnerable populations around the world, climate change has created an unstable food supply across these same regions,” said Christian Man, a research fellow with the global food security program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C.

Global Food Security Index

Countries with higher scores are more food secure

Source: The Economist Intelligence Unit

Ultimately, food security comes down to how rich a country is and how well it manages to diversify its sources of supply. In a world ranking of food security by the Economist Intelligence Unit, Singapore came top, even though it has almost no farmland. At the other end of the table was Venezuela, a country whose decades of oil addiction and mismanagement have left many people starving even though the nation has more than enough land to feed its population.

“Ending food crises is a matter of political resolve, not simply technological fixes,” said Man.