President Trump has clearly decided to deflect blame for the disastrous impact of the COVID-19* pandemic in the United States by attacking China and the World Health Organization (WHO). Of the two, the one that is likely to suffer more, with more consequences for the United States and the rest of the world, is WHO.

Trump has ratcheted up his attacks at an accelerating pace. He first teased at withholding funds from the organization on April 7 but then backtracked only minutes later. Then a week after that, on April 15, he announced that he was suspending U.S. funding for WHO “until its mismanagement, cover-ups, and failures can be investigated.” By the end of April, he had ordered the intelligence community to investigate whether China and WHO had conspired to conceal information about the virus and its origins.

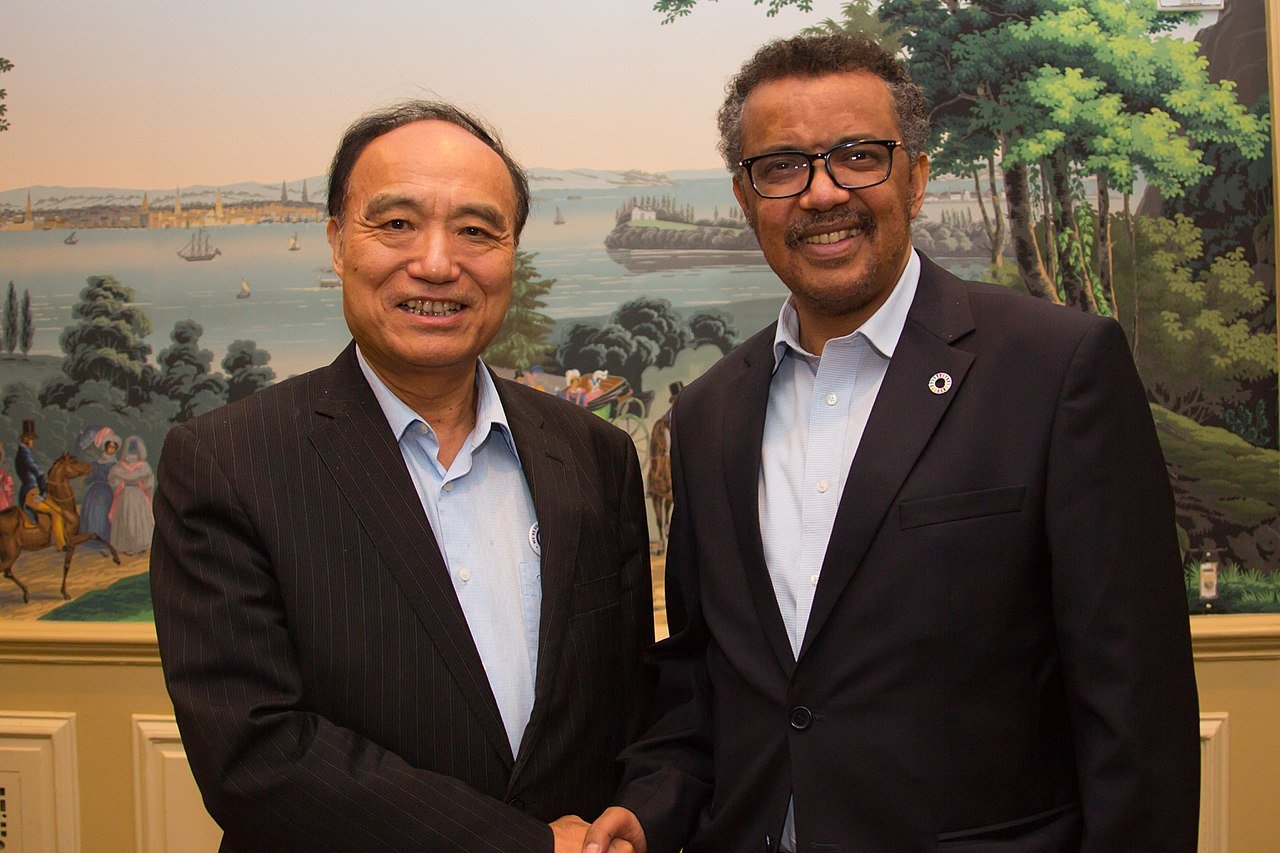

On May 18 Trump sent a letter to, Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the WHO director-general, giving him 30 days to commit to “major substantive improvements” (otherwise unspecified) or the United States would end its funding permanently and reconsider its membership in the organization. Other members, including U.S. allies, voiced their opposition to this and support for the agency. Then, on May 29—just 11 days after his 30-day ultimatum and apparently without consulting his advisers or other relevant officials—Trump inserted into a policy statement on China that he was “terminating our relationship with the World Health Organization” and redirecting funds to other global health needs.

Despite the dramatic charges of mismanagement, cover-ups, and failures, an official fact sheet made only two specific complaints. The first is what David Fidler, a former legal consultant to WHO, interprets as a “failure to provide urgent information.” The charge required interpretation because the official White House document buries it in anti-Chinese rhetoric, such as “the WHO has shown a dangerous bias towards the Chinese government,” and assertions that “the WHO repeatedly parroted the Chinese government’s claims” about the disease and its characteristics. The wording would suggest that Trump is most bothered by the fact that WHO to deferring to China rather than to him. The second specific complaint is that WHO disagreed with the administration regarding the value of travel restrictions, or, as the fact sheet put it, “put political correctness over life-saving measures by opposing travel restrictions.”

These are not justifications for cutting off funding for WHO. As Fidler points out, the administration did not have to struggle with WHO to impose its travel restrictions. WHO is required to make recommendations; it generally makes the same one when it comes to travel restrictions in a health emergency; and the administration is not obliged to comply with it. As for information, the administration has multiple sources, including its own intelligence services. (At one time it actually had specialists on this very issue stationed in Wuhan, China, but it closed that program down.) If the administration had information from an alternative source telling it that China was misinforming WHO about what was happening, then it should have shared that information with WHO. In any event, if WHO was delayed in distributing important information, it was not as delayed as the Trump administration’s responses.

Let us quickly review the sequence of events. WHO received word of an outbreak of an “atypical pneumonia” on December 31, 2019, apparently from sources other than China, and then solicited a confirmation from the Chinese government. China verified the report via Twitter on January 4. (Presumably as a favor to China, WHO used the passive voice in reporting its first information, allowing people to assume that China had officially notified it as it was required to do under the International Health Regulations.) Chinese scientists published the coronavirus genome on January 12. On January 13 a COVID-19 case appeared in Thailand; at this point COVD-19 became a potential matter of international concern rather than a matter solely internal to China and its jurisdiction. WHO tasked a German group to develop a test for it, which was made available to countries on January 16. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) declined to adopt it and then botched its own test, delaying the onset of testing in the United States. China announced on January 20 that the coronavirus was a serious threat and that local authorities had suppressed the information. (Whether true or not in this instance, that is actually a major problem in countries like China, where local authorities face multiple, conflicting demands from the capital and are held responsible for anything that goes wrong, often without regard to actual responsibility.) A WHO delegation visited Wuhan briefly for the first time, on January 20–21, and stated that there was evidence of human-to-human transmission but that more analysis was needed. On January 22, Dr. Tedros, WHO’s director-general, began giving daily press briefings, encouraging countries to engage in testing, contact tracing, and the isolation of infected persons. WHO declared COVID-19 a “public health emergency of international concern” (PHEIC) on January 30. On that day Trump announced the formation of a coronavirus task force under Secretary Alex Azar of the Department of Health and Human Services, and he imposed partial restrictions on travel from China the following day, January 31. In mid-February, Dr. Anthony Fauci of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases said that it could have the makings of a global pandemic. A more substantial WHO visit to Beijing and Wuhan came on February 16–24. On February 25, Dr. Nancy Messonnier, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, said, “Ultimately, we expect we will see community spread in the United States. It’s not a question of if this will happen, but when this will happen, and how many people in this country will have severe illnesses.” She added, “Disruptions to everyday life may be severe, but people might want to start thinking about that now.” Rather than heed the warning, Trump put Vice President Mike Pence in charge of the coronavirus task force on February 26 and instructed him to tamp down the alarmist talk before it spooked the stock market. Following the lead of his son-in-law, Jared Kushner, Trump’s primary concern was that any acknowledgment of a potential crisis—or any overt effort to counter it—might roil the markets and hurt his reelection chances. It was March 15, after the markets had already begun to tank, when the Trump administration recommended social distancing and locking down the economy in the United States.

Some have complained that after its January 30 PHEIC declaration, it took WHO until March 11 to declare a pandemic. But officially, a PHEIC declaration is all there is, and the authority to declare a PHEIC has existed only since 2005; there is no such thing as an official WHO pandemic declaration. It seems that Tedros started using the scarier term pandemic to attract the attention of countries that were still not taking the issue seriously enough. (As an official WHO timeline describes the March 11 statement, “Deeply concerned both by the alarming levels of spread and severity, and by the alarming levels of inaction, WHO made the assessment that COVID-19 can be characterized as a pandemic.” [Emphasis added.]) Trump’s social-distancing decision came six weeks after the PHEIC declaration and weeks after warnings from his own public-health officials. How much did the delay matter? Researchers at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health looked into that question and came up with the following estimates:

In a retrospective analysis, the researchers find that, nationwide, 703,975 confirmed cases (62%) and 35,927 deaths (55%) of reported deaths up to May 3 would have been avoided if observed control measures had been adopted one week earlier—on March 8 instead of March 15. In the New York metropolitan area, 209,987 (80%) of confirmed cases and 17,514 (80%) of deaths would have been avoided if the same sequence of interventions had been applied one week earlier. Had the sequence of control measures occurred two weeks earlier, the nation would have seen a reduction of 960,937 (84%) cases and 53,990 (83%) deaths, and a reduction of 246,082 cases (94%) and 20,427 deaths (94%) in the New York metropolitan area.

A major shortcoming in the administration’s argument is a fundamental failure to understand—or even to try to understand—the issues at hand. Take, for example, this statement: “The WHO put political correctness over life-saving measures by opposing travel restrictions.” Trump, it appears, simply assumes that travel restrictions are life-saving measures. It is indeed possible for travel restrictions to slow the spread of contagions. WHO itself said that restrictions, when imposed early and of limited duration, can give countries time to prepare for the arrival of the contagion (which Trump failed to do, evidently believing that the travel restrictions were sufficient in and of themselves). On the other hand, travel restrictions do not stop the spread of contagions and they cause problems of their own. Apart from the general social and economic disruption, travel restrictions make it harder to get emergency personnel into the affected area in order to combat the outbreak or slow or prevent the spread of the disease to other areas. Additionally, fear of eliciting travel and trade restrictions can lead some countries to cover up their disease outbreaks, producing worse outcomes overall. Also the announcement of imminent travel restrictions can cause panic-driven movement by people who fear being caught in a containment area. Trump did this three times in announcing restrictions related to China, then Iran, then Europe. The Europe-related announcement, in particular, led to a flood of people overwhelming airports—creating large, packed crowds, mixing virus carriers with susceptible subjects—and may well have contributed to the massive outbreak in metropolitan New York. WHO has also stated that travel restrictions can produce a “stigma,” which may be the root of Trump’s reference to “political correctness,” but that is hardly the core of the argument. For these reasons WHO generally advises against restrictions, as do other public-health authorities.

More generally, the administration’s arguments betray a basic misunderstanding of the nature of international organizations. They are rarely independent actors on the global stage. Rather, they are membership associations. WHO serves as a forum for debate among its members—that is, 194 separate countries that are represented in its governing body, the World Health Assembly—on issues of global health, as a vehicle for sharing information, as a pool of technical expertise, as a helper in policy coordination, and as an agent for its members in seeking to achieve common goals related to global health. In doing so, it performs an extremely useful function. But, to put it bluntly, WHO is not in a position to boss China around. It is not a supranational authority (nor, for that matter, is it an instrument of U.S. policy). The only international organization with the capacity to boss member states around is the UN Security Council, which can do so when passing resolutions under Chapter VII of the UN Charter (“Action with Respect to Threats to the Peace, Breaches of the Peace, and Acts of Aggression”). And even in that case—if this had involved a threat to the peace and were being decided by the UN Security Council—China, as a permanent member of the Security Council, could veto any action directed against it. In any event, China, which held the rotating Security Council chairmanship in March, managed to keep the pandemic entirely off the agenda throughout that month. In April, when the Security Council finally did attempt to address the issue, it was stymied both by China’s singular focus on avoiding blame and by the United States’ singular focus on blaming China (and WHO). Thus, nothing of significance was achieved.

Of course, not all of WHO’s 194 bosses have an equal say in what it does, but enough of them do to complicate any controversial decision it has to make. That is especially true when members disagree or fight each other. In this case, the repeated efforts of U.S. representatives to condemn WHO’s pro-Chinese rhetoric, highlight the Chinese origins of the pandemic, and press for Taiwan’s last-minute addition to the World Health Assembly have served no purpose but to rile the Chinese leadership and obstruct progress in dealing with the disease. WHO is a repository for information filed by member states, and thus it is highly dependent on the member states’ willingness to issue reports. It was not in a position to force China to allow its inspectors into Wuhan, and China did not allow it to do so for several weeks. If WHO was unseemly in its praise of China, then presumably Tedros believed, rightly or wrongly, that doing so was necessary to elicit China’s cooperation. Naming-and-shaming, WHO’s one other alternative, can be counterproductive when dealing with thin-skinned governments. (An administration in which cabinet meetings begin with secretaries singing the praises of the president ought to understand this.) The political situation in the United States being what it is, we have grown accustomed to focusing on the rhetoric instead of the substance—such as Tedros’s admonitions to engage in testing, contact tracing, and quarantines—and have come to view the expression of outrage as an end in itself. We thus denounce Tedros for not wasting his time in counterproductive denunciations. In any event, it was WHO that successfully solicited China’s acknowledgment of the outbreak in the first place, provided the first COVID-19 tests, and declared the PHEIC. It does not deserve to be treated so harshly.

Trump’s response to the pandemic—which he seems to view primarily as a political problem—was twofold: (1) Hope the pandemic works itself out, and (2) Deflect the blame onto someone else. With regard to the domestic response to the pandemic, he has shifted the blame to the state governors, who he insists are responsible for such things. With regard to the causes of the pandemic, he has shifted the blame to China and WHO. The information failures for which Trump holds WHO responsible are primarily the fault of Chinese leaders who delayed and deceived, and even that was valid for only a few weeks.

Trump’s answer to this situation—rather than cooperate to deal with the pandemic—was to punish and defund WHO in the midst of the ongoing crisis. This does not further any positive goal. The possible consequences of this are also twofold. First, the real target of the punishment will be world health. Many countries do not have the wherewithal to fight a pandemic (and innumerable other health issues) on their own and rely on assistance from WHO. They will suffer and also serve as sources of disease for others. Americans will also suffer if the world’s unified response to infectious disease is undermined. Moreover, the United States will lose WHO’s vantage point with regard to looming health threats, which ironically is especially important in China. China’s combination of diverse live animals in close proximity to large numbers of people along with modern transportation infrastructure makes it a prolific source of infectious disease. (Ironically, China’s role as a source of disease increases the importance to WHO of its cooperation.)

Second, it could result in the United States ceding its place of leadership to China, a process already under way. The fact that China has recently pledged an additional $2 billion to WHO—nearly equivalent to the agency’s entire budget in a normal year—suggests that this is likely. If Trump was serious about his complaint that China had too much influence in the organization, this is hardly the way to resolve the issue.

Of course, WHO and international organizations in general are of secondary interest to Trump, well behind his interest in personal loyalty and his own political future, as indicated by some of his personnel decisions. His first Assistant Secretary of State for International Organization Affairs and a senior adviser in that bureau were the subjects of a devastating inspector general’s report in August 2019 in which they were accused of mistreatment and harassment of staffers and retaliation against those deemed insufficiently loyal to President Trump. (The adviser had already left the department; the assistant secretary retired on his own terms in November; the inspector general who wrote the report was fired in May 2020.) As acting assistant secretary, Trump then appointed a former Sarah Palin associate known primarily for her ties to evangelical Christians and opposition to abortion. A Trump loyalist from the Presidential Personnel Office, with a reputation for assessing the loyalties of applicants for apolitical government positions, was then named Deputy Assistant Secretary for Management Issues with responsibilities for budgets, senior appointments to international organizations, and UN elections. As for WHO, the United States did not even have a representative on the agency’s rotating executive board until May 7, 2020, although the U.S. term on the board had begun in 2018 and expires in 2021. The administration nominated an Assistant Secretary of Health and Human Services, a Trump appointee who was previously best known for being fired as the head of vaccine development at Texas A&M University in 2015. In fact, the administration nominated him three times—in November 2018, January 2019, and March 2020—before the Republican-led Senate took any action toward confirmation, suggesting a lack of confidence in the choice. With regard to the WHO budget, the United States was already in arrears on its dues for 2019, and Trump’s budget proposal for Fiscal Year 2021 had called for cutting the contribution to WHO by 53 percent even before the COVID-19 issue had arisen.

In the meantime, China has taken advantage of U.S. disinterest in international organizations and increased its influence within the UN and its allied agencies. Chinese officials now run four UN agencies, and Tedros, an Ethiopian, was promoted for the WHO position by China as well as the African bloc. In response to China’s growing influence, instead of showing leadership and engaging more energetically in multilateral diplomacy, the Trump administration has taken the adversarial approach of naming a special envoy for countering Chinese influence at the UN (formally, special envoy for multilateral integrity). This approach is likely to divert attention from the actual tasks of the UN’s specialized agencies and alienate other countries. If the United States wants to keep WHO “honest” and balance the influence of China, then it must be active within the agency, act as a counterweight, and stop emulating China’s practice of prioritizing the protection of its own image. What Trump is doing merely cedes further influence to China.

As for the fate of WHO, much will depend on whether the United States actually leaves. Under U.S. law, withdrawal from WHO requires a year’s notice and full payment of all arrears, so things could still change. There will be calls for reforms either way, and there will certainly be room for reform. But we should keep in mind that even after reforms, WHO will not boss China around. That’s just not how it works.

*Multiple terms have been used to identify the category of virus, the specific virus, and the disease it causes. The category is coronavirus. The specific coronavirus, first encountered in Wuhan, China, in 2019, was temporarily labeled Novel Coronavirus 2019, or nCoV-19; then it was officially named Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2, or SARS-CoV-2. The disease it causes is Coronavirus Disease 2019, or COVID-19.