Troubles in Quinn Country

In the Irish borderlands, Sean Quinn was always known as a tough businessman. But he was hugely successful and created thousands of jobs.

A local hero.

And then it all went wrong.

Kevin Lunney’s mind wandered as he drove up the country lane to his home in Kinawley, County Fermanagh, a few miles north of the invisible line where the United Kingdom ends and the Republic of Ireland begins. It was September 2019, an unusually bright afternoon. He reminded himself to mow the lawn. Perhaps it would be his last chance to do so before winter.

Before he reached the house, as he later told the BBC, Lunney noticed a white car parked up ahead, engine idling. The road was narrow, barely wide enough for a single vehicle, and enclosed on both sides by thick hedgerows. As Lunney slowed his SUV to a stop about 30 yards away, he felt his pulse quicken. Fermanagh is an insular place at the best of times, where unfamiliar cars attract suspicious glances. Lately, events at his employer had everyone on edge.

Lunney was a director at Quinn Industrial Holdings, an offshoot of a vast manufacturing and insurance conglomerate that had gone through an acrimonious breakup and wound up in the hands of hedge funds. Ever since, QIH had been the target of sabotage, arson, and death threats—the kind of activity not seen since the dark days of the Troubles.

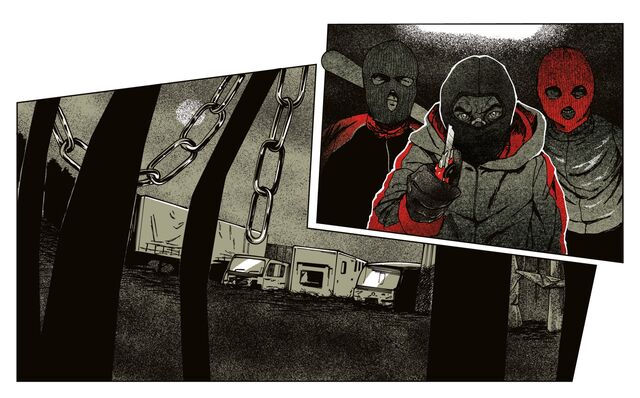

Maybe they’re just lost, Lunney told himself, peering through his windshield at the white car. Suddenly the vehicle began reversing at high speed, leaping over the road’s rutted surface. He had no time to react before it smashed into the front of his truck. Two men wearing balaclavas got out. As Lunney fumbled for his cellphone, his side windows imploded. One of the men pulled him into the road and relieved him of his phone. A third masked man appeared and held a Stanley knife to his throat. “Get into that,” he said, gesturing to the trunk of a black Audi waiting nearby. “If you don’t get into that, we’re going to kill you.”

Twelve years earlier, Sean Quinn stood in the ballroom of the Slieve Russell Hotel and attempted a speech. It was March 7, 2007, a decade since his last public remarks, and he stumbled over his opening lines. “I had stuff wrote down to say, and I’m not sure where I am in all of that now,” he said, to laughter from the crowd, according to an account of the event in Citizen Quinn, a book about his rise and fall.

Quinn, then 60, warmed to the task as he described how he’d left school at 15 to work on the family farm in nearby Teemore, a mile from the Irish border. In those days he rode around on a tractor and captained the local Gaelic football team. In his 20s, Quinn said, he’d borrowed £100 to buy an excavator after discovering that the hill behind his home was filled with valuable sand, shale, and gravel. Before long he diversified into cement, then glass, then property, then insurance.

Such was Quinn’s impact on the landscape—replacing sheep pasture with smokestacks and gigantic machines for crushing rock—that the entire region from Enniskillen to Ballyconnell became popularly known as Quinn Country. “We come from a very simple background, and we tried to make business always simple,” he told the crowd gathered in the Slieve Russell’s banquet hall. “We never got a feasibility study done in our lives.”

Along the border, this was the stuff of folklore: the uneducated Catholic farm boy who’d used his wits and local knowledge to create thousands of jobs in an area better known for sectarian violence. When Quinn met his friends at the bar of the Slieve Russell, a luxury hotel he’d built on the site of a 4,000-year-old tomb, they were expected to buy a round or two.

But there was more to Quinn. He was also a ruthless businessman who took on Ireland’s biggest manufacturers and family-run gravel suppliers with equal zeal. He was a proud Irish republican who was happy nonetheless to take money from the hated British in the form of generous government grants for equipment and building roads. And he was lavishly rich: a humble son of the soil with a 10-seater Dassault Falcon private jet. In 2007, the year of his Slieve Russell speech, Forbes estimated his family fortune at $6 billion, making him the 164th-richest person in the world.

Lunney had joined the business in 1995 as an ambitious 26-year-old management consultant. He was hired to help run Quinn Insurance Ltd., which had grown from covering Quinn’s fleet of green cement trucks to become a car and home insurer in the U.K. Soft‑spoken and shy, Lunney impressed Quinn with his work ethic and eye for detail. Like his boss he’d grown up on a borderland farm, the bookish one among 10 siblings, some of whom would also end up working for the area’s most successful businessman. When Quinn decided to move part of his family’s wealth offshore, into real estate in Russia and India, it was Lunney he sent to scout out opportunities.

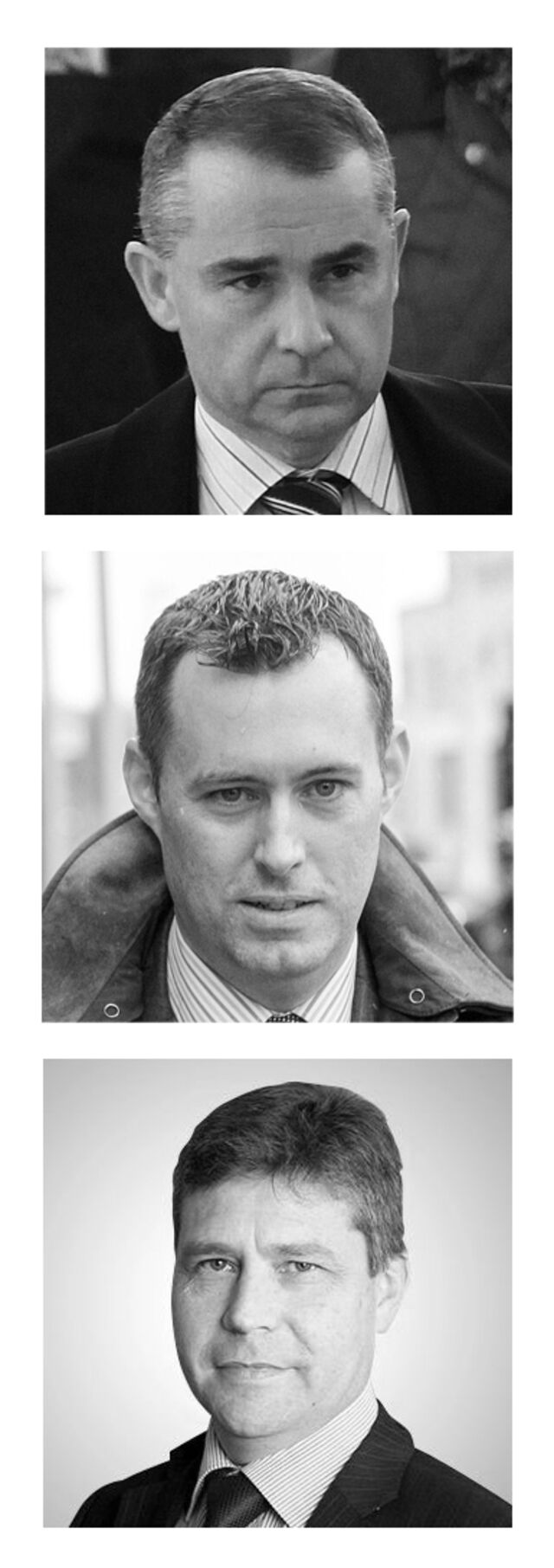

Lunney was one of three locals who managed the boss’s empire. Quinn Group’s chief executive officer, Liam McCaffrey, hailed from Enniskillen. Its chief financial officer, Dara O’Reilly, was from a few miles away, in County Cavan. Quinn called the management team his “boys.” Within the company they were known as the “Holy Trinity,” according to the authors of Citizen Quinn.

“I was always very greedy,” Quinn said, winding up his speech at the Slieve Russell. “I was never happy with what we had.” That insatiable appetite would prove to be his downfall. Unknown to most of the audience, Quinn had secretly made a huge, personal bet on Anglo Irish Bank, right before the biggest banking crisis of the modern era.

The trade, using instruments called contracts for differences, meant Quinn didn’t have to buy shares or declare his position. He’d make money if the stock rose and owe money if it fell. When the 2008 crash hit, and Anglo shares started to plummet, Quinn doubled down, increasing the position, and taking hundreds of millions of euros out of his insurance company to cover the cost. Where others might have cut their losses, Quinn could see only the upside. The lower Anglo Irish shares went, the more he stood to make when they recovered.

They never did. The bank was nationalized in January 2009, leaving Quinn’s companies owing €2.4 billion ($3.1 billion) to the Irish state, plus an additional billion or so to various banks and bondholders. (After the crisis he’d appear in Forbes magazine again, this time under the headline “Sean Quinn: The Biggest Loser.”) When it became clear his companies couldn’t repay the loans, creditors pushed for a reorganization, but Quinn refused, insisting he deserved a second chance.

On April 14, 2011, he was summoned to Anglo Irish’s headquarters in Dublin for a 9:30 a.m. meeting. As he made his way toward the capital, a convoy of bankers, lawyers, and security personnel was headed in the opposite direction, toward Quinn’s headquarters in Derrylin.

Flanked by Lunney and O’Reilly, Quinn sat down across from a former government minister who’d recently been appointed a director of the nationalized bank. The official told Quinn that Anglo Irish had reached a deal with his creditors. They’d seized control of Quinn Group and its operations. A judge had already signed the necessary court order. “Why?” Quinn asked, after a moment of stunned silence. “We’re happy to pay all your money back.”

“It’s done, Sean,” the official replied.

The seizure of the Quinn companies took a single day. Security teams swept the offices, and a locksmith changed the locks. Lunney and the other members of the Holy Trinity were fired, replaced by outside managers appointed by the creditors. The staff seemed shocked rather than rebellious.

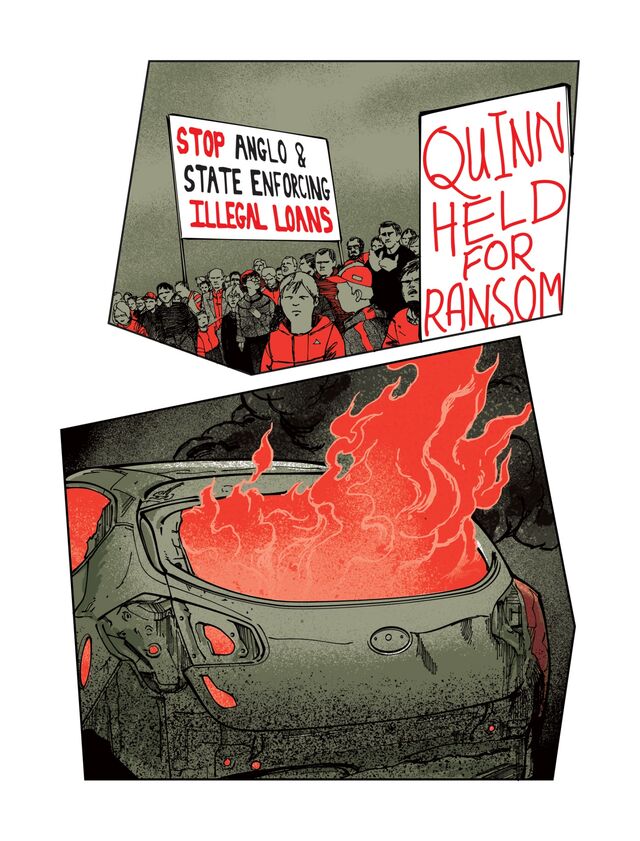

The first indication that Quinn’s supporters wouldn’t go quietly came a few days later. More than a hundred people turned up in Derrylin at 7 a.m. to deliver a letter of protest. In the excitement they forced their way past security guards and into the building. During that first week someone stole a large dump truck, crashed it into the front gates, and left it there, blocking the entrance. When the regular driver was asked to move it, he refused, saying, “I can’t. I’m going to be targeted.”

Meanwhile, Quinn was campaigning to be reinstated, using a tire factory owned by Tony Lunney, one of Kevin’s brothers, as his base of operations. Tony, who still worked at Quinn Group, was given the nickname “Tony Two-Phones” by the new management—they thought he had one handset for work and another for updating Sean Quinn. Tony Lunney denies this, via a QIH spokesman, saying his second phone was a BlackBerry for email.

The Quinn camp sent letters to politicians and church leaders, decrying the great man’s treatment, and websites sprang up with incendiary allegations about the new leaders. Meanwhile, minor acts of sabotage occurred on an almost weekly basis: There were cut power cables, blocked thoroughfares, and arson. It was impossible for the incoming management to know exactly who was behind the vandalism, beyond that it was being carried out by Quinn’s supporters. (Quinn denies any knowledge of or involvement in vandalism or any other criminal activity.) Despite everything that had happened—or perhaps because of it—he remained a revered figure in the area.

A significant proportion of the once-impoverished region’s residents owed Sean Quinn their livelihood. His former companies employed more than 1,000 workers in the border counties and many more elsewhere in Ireland and the U.K. Those not directly employed fed off the Quinn economy, whether pubs and restaurants or gas stations and real estate agents. Some locals even credited Quinn with halting the mass emigration that had drained other parts of the country of working-age citizens and separated parents from their children.

In July 2012 thousands thronged the streets of Ballyconnell for a rally. Holding back tears, Quinn led a march through the town—his wife, Patricia, by his side—as supporters waved handmade placards denouncing the bank “scam” that had robbed him of his fortune. A priest gave a speech in Quinn’s honor, as did Mickey Harte, the manager of Tyrone, a championship-winning Gaelic football team. “Evil prevails when good people do nothing,” Harte said to roars of applause.

Away from the border, Quinn battled to hold on to whatever he could. Hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of Quinn family real estate was shuffled between offshore jurisdictions and out of the grasp of exasperated government debt collectors. Quinn denied any knowledge of the transactions, but a judge didn’t believe him, and in November 2012 he was sentenced to nine weeks in prison for contempt of court. The decision only served to heighten his martyrdom. Local songwriter Barry Murray penned a protest song. “Exploitation. Isolation. Defamation. Incarceration. Trial and tribulation be,” ran the chorus. “Sean Quinn will get his victory, just you wait and see.”

For the bankers and lawyers brought in to salvage Quinn’s former business, it was hard to understand the outpouring of emotion for a man who, by his own admission, had risked it all on a gamble. But the perceived persecution of this proud republican by powerful outside forces echoed the history and character of the region. During the 1970s and ’80s, when the Provisional IRA fought an armed rebellion against British security services and loyalist paramilitaries, the border was a focal point for violence. Fermanagh gained a fearsome reputation for Irish Republican Army activity, standing alongside Bogside and Armagh as place names synonymous with terror. Police dared not linger, speeding through in armored cars, while the army blew up roads to stop the flow of guns and gunmen across the border.

In Quinn Country, everyone knew someone who had taken up arms or even taken a life. They were neighbors, friends, and business partners. And all along, Quinn thrived. In his 1987 book, Walking Along the Border, Colm Tóibín recounted the story of how Quinn had once punched a British soldier at a checkpoint and escaped without retaliation because of his standing in the community. In Tóibín’s telling, though Quinn was a nationalist, he was more interested in “making money and having a good time” than political causes.

Many of the executives brought in by creditors to run Quinn’s former companies were outsiders, from Dublin, London, or Glasgow. They’d been warned about the region’s reputation but were still taken aback by the hostility they encountered. While the new CEO was on vacation in 2011, his car was set on fire by two men in balaclavas. Later, two executives having dinner at a local Chinese restaurant received an anonymous phone call. “Leave or you’ll be killed,” they were told. In 2013 officers of An Garda Síochána, Ireland’s National Police and Security Service, visited board members to warn them that their lives were at risk. A gangster named Cyril “Dublin Jimmy” McGuinness had been released from prison and was rumored to have allied himself with a pro-Quinn faction.

McGuinness was infamous in Ireland—a wild-eyed career criminal who’d been convicted for stealing farm machinery, dumping toxic waste, perjury, assault, and forgery. During the Troubles he’d worked for the IRA, according to media reports. Now, the police said, he was a hired gun, issuing death threats and doling out attacks for a few thousand euros at a time.

Shaken, the executives tightened security measures and focused on trying to sell off the business to repay creditors as quickly as possible. Some assets were successfully sold, but just as often, when they were closing in on a deal, the interested party was threatened and ended up walking away. When rival cement producer Lagan Group entered talks about a potential merger, its chairman got a rifle bullet in the mail, with a ransom-style message pasted together out of newspaper cuttings: “[IS] [THIS] [WHAT] [U] [WANT].”

By the middle of 2014, the total number of attacks against the former Quinn companies and competitors had reached 70. Neither the police nor private security contractors found any hard evidence of who was directing the campaign. Few people were willing to help investigators in an area where informing had historically carried a death sentence. The Irish Times called it a “conspiracy of silence.” If the same thing happened in Dublin at the regional headquarters of Microsoft Corp., the newspaper wrote, it would be treated as a national emergency.

With potential buyers for Quinn businesses deterred by the threat of violence, an opportunity arose that once seemed inconceivable: the return of Sean Quinn. Backed by a group of local businessmen, Quinn’s three lieutenants—McCaffrey, O’Reilly, and Lunney—formed an entity called Quinn Business Retention Co., or QBRC, to bid for the company’s assets. Quinn himself would return to the top of the business, everyone involved in the bid agreed, once his legal problems were resolved. First, QBRC needed to find financial backing.

By now the company’s fate resided in the hands of three American hedge funds—Brigade Capital Management, Silver Point Capital, and Contrarian Capital—which had bought up Quinn Group debt on the cheap. When they learned that former Quinn executives were interested in buying back parts of the business, they offered to team up and bankroll the acquisition. Under the terms of the proposed deal, Lunney and the others would get a generous salary and a minority stake in the new enterprise. But there was one condition: Sean Quinn couldn’t be involved.

The U.S. investors, who among them managed a total of $15 billion, had no desire to get into business with Quinn, in their eyes a former convict who was still officially bankrupt. After some persuasion from the QBRC team, they agreed to employ Quinn as a consultant at €500,000 ($600,000) a year, but he was barred from owning shares. With little choice, Quinn reluctantly agreed. In December 2014, QBRC and the hedge funds finalized a deal to buy the construction materials and packaging businesses for €85 million. The new company would be called Quinn Industrial Holdings, or QIH.

The following week, Lunney, McCaffrey, O’Reilly, and the other new directors were in the boardroom when they heard a cheer erupt from the floor below. “What’s that?” someone asked. “I think I know,” McCaffrey said. One of the group went down and saw Quinn, a smile on his face, walking around the office with a silver tray of whiskey and beer, handing out drinks. The executives looked at one another. None of them had invited him.

As far as the American owners were concerned, Quinn’s role was largely ceremonial. The press, however, followed his lead. “Return of the King,” read a headline in the Sunday Business Post. Another paper described the event as “the second coming.”

Quinn still saw himself as the boss, and it quickly became clear that he was unwilling to play any other role. He made his disdain for the QIH deal plain at the first meeting, in January 2015, when he sat down, scowling, in his familiar seat at the head of the boardroom table. Things were going to go back to the way they were, Quinn announced, with him in charge. Lunney, McCaffrey, and the rest were being paid too much, he said, and he didn’t approve of them owning shares when he didn’t. “You’re a shower of grabbers,” he fumed, according to several people present.

A few weeks later, after the owners agreed to sell the flagship glass business to a Spanish conglomerate, Quinn raged in the QIH boardroom, in front of the buyer’s chairman. “Youse are all f---ing gangsters,” he said.

Quinn was convinced he’d been sidelined, and any meeting he attended after that quickly descended into recrimination. When he was angry, he had a habit of referring to himself in the third person. “When Sean Quinn says he is going to do something, Sean Quinn does it,” he growled, telling the Holy Trinity they had “got to go.” During one encounter, Lunney grew visibly upset and pleaded with his former mentor to be reasonable. Instead, Quinn wrote to the hedge fund owners, accusing Lunney and the other managers of fraud and self-dealing (allegations the Americans investigated and concluded were unfounded).

For the first time, Lunney, McCaffrey, and O’Reilly experienced what it was like to be an enemy of Sean Quinn in Quinn Country. Signs were erected in Derrylin saying, “Vultures out” and “Money grabbing traitors and informers.” A website was set up by an entity calling itself the Cavan, Fermanagh, Leitrim Community Group, hailing Quinn for creating a “beautiful industrial oasis” and attacking the scavengers circling to “feast on this tasty carcass.”

“There’s no mistake that Cromwell is indeed alive and kicking in our own backyard,” a contributor wrote, evoking the republican boogeyman, Oliver Cromwell, who led the English forces that brutalized Ireland in the 17th century.

In December 2015, Lunney discovered a pig’s head in his front garden after the company Christmas party. His young children were with him at the time.

Eventually, the owners—Brigade, Silver Point, and Contrarian—agreed to fly over and meet Quinn face to face. All three were seasoned distressed investors, accustomed to volatile situations—but this was something else. In a Dublin hotel, the funds’ representatives assured Quinn they wouldn’t be around forever. If he bided his time and worked with the management team, they said, there might be a pathway for him to regain ownership. Quinn responded by demanding the Holy Trinity be fired.

“We view your requests as unreasonable,” the hedge funds wrote to Quinn in a joint letter, seen by Bloomberg Businessweek, dated May 5, 2016. They dismissed the former owner’s claim that locals were upset about his treatment. “The hurt you refer to can only reflect your own frustrations, as we can assure you there is absolutely no evidence of any widespread ‘hurt’ in the local community.” Quinn wrote back saying he would continue to work at the business, whether they paid him to or not. Later that month his consulting contract was terminated.

For the next two years, Quinn holed up in his sprawling home next to the Slieve Russell, the hotel he once owned, maintaining a low profile while sporadic acts of violence and intimidation continued. Then, in the spring of 2019, word got around that QIH’s hedge fund owners had appointed an investment bank to explore sale options. If the deal went ahead, it would take the company even further out of Quinn’s reach and leave his supporters facing a future in which the area’s most important company resided permanently in the hands of outsiders.

A few months later, in September, Lunney was abducted as he drove home from work. He gave an account of what happened to a Northern Ireland edition of Spotlight, a BBC current affairs program—the only time he has spoken publicly about the incident. Asked by Businessweek about that version of events, Lunney, through a company spokesman, didn’t refute it but declined to be interviewed.

Inside the Audi’s trunk, Lunney thought about his wife, Bronagh, and their six children. Freeing his hands, he found a latch and popped open the trunk. He waved his arms, but passing drivers either didn’t see him or pretended not to.

The Audi slowed, and Lunney jumped, tumbling out into the road. But the car stopped, and one of the men got out and threw him back inside, slamming the trunk. As they sped off again, Lunney heard the men talking into a cellphone: “Boss, the man has resisted.”

Eventually the car pulled over. Lunney had a few seconds to take in what looked like an overgrown farmyard before one of the men put a bag over his head and marched him through a door into an enclosed space. When they yanked up the bag, Lunney, the farmer’s son, recognized immediately he was inside a wooden horse trailer, its interior painted blue.

The captor with the Stanley knife approached and said, “You know why you are here.” Lunney said he didn’t. “It’s because of QIH. You’re going to resign.” Lunney agreed that he would. “Give me your fingers,” the man said. He pushed the blade under Lunney’s fingernails, drawing blood, while his two companions held Lunney’s arms. One of them talked about needing bleach. They put the bag back over Lunney’s eyes and bound his hands with cable ties. It was growing dark outside. Two of the men got up and left. Lunney heard them start the Audi and drive away. He bowed his head and silently began to pray.

When Lunney’s captors returned, they poured bleach over his hands then rubbed it into his bloody fingernails with a cloth. The pain was so great and the bleach fumes so strong, Lunney thought he might pass out. The kidnappers cut the cable ties binding his hands and slashed off his clothes, leaving him shivering and bloody in a pair of boxer shorts.

“Have you done his face?” one of the men asked. They squirted bleach into his eyes and mouth. “You’re going to resign,” they kept saying. “Tell the others to resign. We know you. We’ve been watching you.”

I’ll do anything you say, Lunney pleaded.

But there was more. One of the men took out what looked like a wooden bat and struck Lunney’s leg as hard as he could. “Did it break?” the man holding him up asked. To be certain, they hit Lunney in the same spot. The pain was a hundred times worse.

Before they could let Lunney go, they explained, they needed to mark him. The leader slashed his face with the knife then took the blade to his chest. “Just so you remember why you are here,” he said, as he carved three letters into Lunney’s flesh: Q I H.

They dragged Lunney to another vehicle and drove him to a remote country lane. “If you turn around and look at this van, we’re gonna shoot you,” one of the masked men told him. “If we hear of you giving a statement to [the Garda], we’re gonna shoot you.”

Lunney was left alone, bleeding and half-naked, at the side of a road. A car flew past. The adrenaline of the attack was wearing off, and the pain of his injuries roared to the surface. After what seemed like hours, he spotted a light up ahead, probably a house, and began crawling toward it.

Two weeks later, Father Oliver O’Reilly addressed the attack on Lunney during Sunday Mass at Our Lady of Lourdes Church in Ballyconnell. Standing in front of a carved wooden pulpit and wearing a green chasuble, he delivered the sermon, his words echoing around the church.

“This senseless atrocity follows years of threats, abuse, lies, and various forms of violent intimidation against the directors of Quinn Industrial Holdings,” O’Reilly said, looking out at the congregation. “There has been a Mafia-style group with its own ‘Godfather’ operating in our region for some time.” Behind it all is a “powerful paymaster and his criminal gang.” He called on his parishioners not to ignore the “cancer of evil in our midst” and criticized those who had stoked hatred with angry speeches at public meetings.

Even though his name wasn’t mentioned, Quinn was furious. He visited the priest to tell him he had “no hand, act, or part” in what had happened to Lunney. Then he complained to a more senior member of the Catholic Church. That clergyman appealed to Quinn not to say anything that could be interpreted as incitement. “If telling the truth is incitement, I’m guilty,” Quinn replied.

Shortly after the kidnapping, another rally was held in Quinn Country, this time in support of Lunney and his colleagues. For years, residents on the border had stayed quiet as acts of violence were carried out on their doorsteps, either out of loyalty to Quinn or in fear of the repercussions. But with Lunney’s attack, something changed. Hundreds marched to Derrylin, including QIH employees dressed in high-visibility yellow vests, for an event attended by politicians from both sides of the border. Lunney, still recovering, stayed at home.

After almost a decade of apparent inaction, police in the Republic and Northern Ireland announced an unprecedented cross-border operation to hunt for the perpetrators. At dawn on Nov. 8 they descended on a quiet street in Buxton, in northern England, and broke down the door of the house where Dublin Jimmy, the ex-IRA gangster, was hiding out. While police searched the property, Dublin Jimmy sat on the sofa with a cup of tea, smoked three cigarettes—then collapsed from a heart attack. He was pronounced dead at 10 a.m. Officers recovered documents, computers, and several mobile phones from the house.

Later that month four men were arrested and charged over the assault and false imprisonment of Lunney. They’re scheduled to stand trial in 2021. At the time of writing, they had yet to issue a plea. Meanwhile, Quinn Country remains as troubled as ever. In February a car belonging to a QIH family member was firebombed, ending a brief respite after Lunney’s kidnapping. “The community is divided,” said Tony Doonan, a member of the pro-Quinn CFL Community Group and a regular at Quinn’s weekly card game. “The last time it was as toxic as this was 30 years ago, when British soldiers were here.”

Back at Quinn headquarters, the QIH directors have no plans to resign. They are living with police protection, security cameras, and panic buttons but say they won’t be driven out. “It’s now about the whole reputation of the area,” said CEO McCaffrey in an interview with Businessweek in February. “Is this the kind of standard that we have? The thought of this activity being allowed to succeed is just wrong.”

Opposite the boardroom, Quinn’s old office sits empty. More than two years have passed since he was pushed out of the company, yet the room remains exactly as he left it. A stack of business cards bearing the founder’s name sits on the table, next to a calculator and a list of phone numbers. The only visible luxury is a well-worn leather chair.

Quinn’s seven-bedroom house is on the outskirts of Ballyconnell, next to a wind-swept lake just south of the Irish border, a few miles from where he grew up. Built in 2006, at the peak of his success, the property has its own leisure complex, indoor putting green, and helipad. From the outside, however, it retains an austere quality, its stone walls reflecting the color of the sky and the lake. To gain entry, visitors pass through a cast-iron gate and make their way down a winding driveway. On a February morning, Quinn opened the double-height wooden door and beckoned Businessweek reporters to come inside, away from the sleet and rain.

For years, as his empire was expanding, Quinn shunned interviews. Before 2008, “I wouldn’t have done 10 interviews in 30-odd years,” he said, leading the way along a marble corridor into the kitchen and to a dining table overlooking the water. “We always felt that action was better than words, you know?” He’s 73 now and seems determined to regain control of the narrative. He’s working on a documentary that he hopes will counteract what he sees as the lies in the media.

Patricia, whom Quinn married before the first factory was built, brought tea and biscuits on a china plate. Quinn looked tired as he described his early years. “I’d no experience in business, just picked it up as I went along and made plenty of mistakes and learned from them,” he said. He never expected to become as successful as he did but credits his ability to foresee big economic trends and a fierce desire to win. “It’s not the money. The money was never important to me.”

When the conversation turned to his Anglo Irish trades, Quinn became more animated. “I should have pulled back at a certain stage,” he conceded, his dark eyes fixing on a spot on the window. “Cut, and just lose my billion. I have to accept that,” he said. What he’s never been willing to accept is the way the politicians from Dublin and foreign financiers broke up and sold off the business he built from nothing. “If you have a business that went from £8,000 of profit in 1973 to £550 million of profit in 2007, and never had any issue with dishonesty or fraud, why would you close it down?” he asked. “It just makes no sense.”

In Quinn’s view, the deal Lunney and the other directors struck with the U.S. investors was designed to exclude him. “You wouldn’t believe how they treated me,” he said, becoming indignant as he recounted being barred from meetings. “I was the small boy, and they were the men in charge.” The ultimate betrayal, in Quinn’s eyes, was the sale of the glass business before he’d had a realistic chance to mount his own bid. Lunney, McCaffrey, and the rest were running QIH into the ground, he said.

Asked about the violence and intimidation that had been directed at his rivals, Quinn walked across the kitchen, picked out a toothpick from a packet, and sat back down. “Let’s put it this way: In order to run a business, you need some fundamentals. And the fundamentals would be respect,” he said. “And if the staff and the community knows that they have knifed Sean Quinn in the back and taken his business, are they going to support them?”

Quinn, pressed on whether he had any personal involvement in any of the attacks or menacing behavior, removed the toothpick from his teeth and reeled off a list of the allegations made against him: “Sean is disruptive … Sean’s responsible; he’s the paymaster; he’s this, that, and the other,” he said, with a wry laugh. “They can say whatever they want, but there’s no evidence to support any of it. None. And let me tell you. You won’t find it. You won’t find it.”

Lunney’s abduction was stupid and barbaric, he said, and it has damaged the Quinn family’s standing in the area. “But all those directors know I had no hand, act, or part” in it. As the interview concluded, the conversation turned to whether Quinn had any desire to return to the business, after all that had happened. “I don’t think so,” he said. Well, perhaps, he clarified, if someone came to ask for his help. “It’d depend on the conditions.” —With Rodney Edwards