In the long narrative that was John Lewis’ life, his time as a member of the Atlanta City Council can be missed in the blink of an eye.

His 1998 autobiography, “Walking with the Wind,” devotes only five of the book’s 475-pages to his time in city government. He served a little more than one term, from his election in 1981 until his 1986 resignation to run for Congress.

He didn’t sponsor any significant legislation and never chaired a committee, which he thought was political payback for not being a “team player.”

Andre Dickens, elected to Lewis’s old seat in 2013, was unaware that Lewis had even served at city hall. “It wasn’t talked about much,” Dickens said.

But Lewis’ brief term — having his idealism pressure tested by Atlanta politics — served as the springboard to the politician he became in representing Atlanta for more than 33 years in Washington: the unwavering conscience of the U.S. Congress.

Life after the civil rights movement

In the early 1970s, when the civil rights movement had ended, Lewis settled in Atlanta to run the Voter Education Project. He was steeped in civil rights but was beginning to dip his toes into politics. He helped Andrew Young’s congressional campaigns and ran unsuccessfully for his seat after President Jimmy Carter appointed Young as the United Nations ambassador in 1977.

Lewis also followed Carter to Washington, the new president appointing him the head of ACTION, the national volunteer coordinating agency. But Lewis quit in 1979 to return to Atlanta.

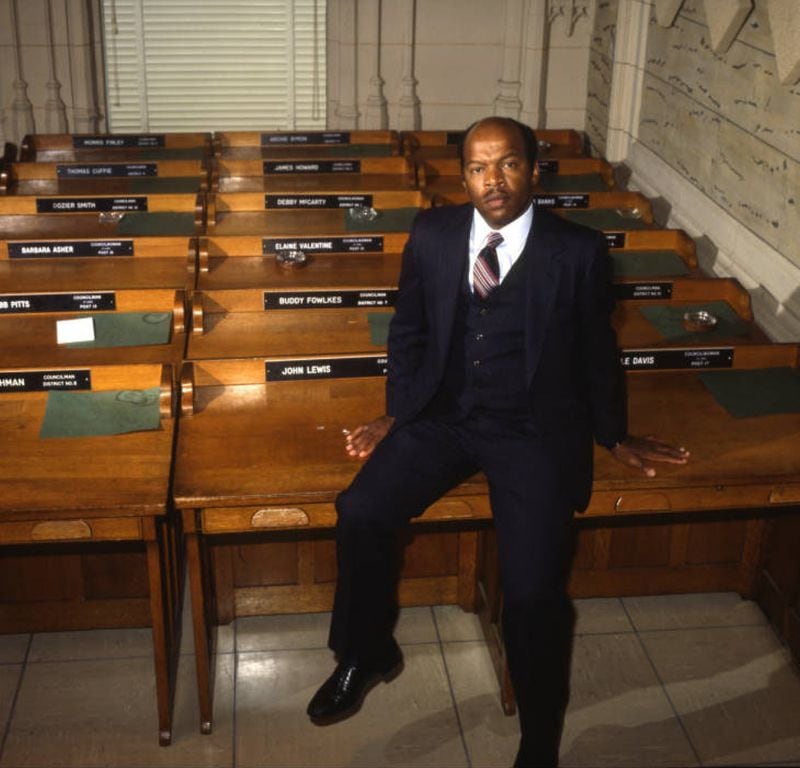

Two years later, on Oct. 7, 1981, Lewis won a city council seat with 69% of the vote, crushing councilman Jack Summer, who had spent 24 years in the position.

Credit: Floyd Edwin Jillson

Credit: Floyd Edwin Jillson

Lewis arrived at council chambers as a political neophyte, but with a huge following and his reputation as a civil rights leader.

That was the year the Atlanta found itself with its first Black-majority city council.

Young, home from a stint as U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations, was elected mayor. Two other freshmen members also joined the council, Myrtle Davis and Bill Campbell.

But Lewis constantly butted heads with the status quo, and other council members considered him an outsider.

“I came in here not being a part of any established group. I’m not part of any structure,” Lewis told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution in 1982. “It’s not that I’m a maverick. I’m just not obligated. All I brought with me were some set ideas about what government ought to be like.”

In his autobiography, he was blunter:

“Council members complained over and over again that I was not a ‘team player,’” Lewis wrote. “I answered that ‘team player’ was code for ‘He can’t be bought,’” his autobiography says.

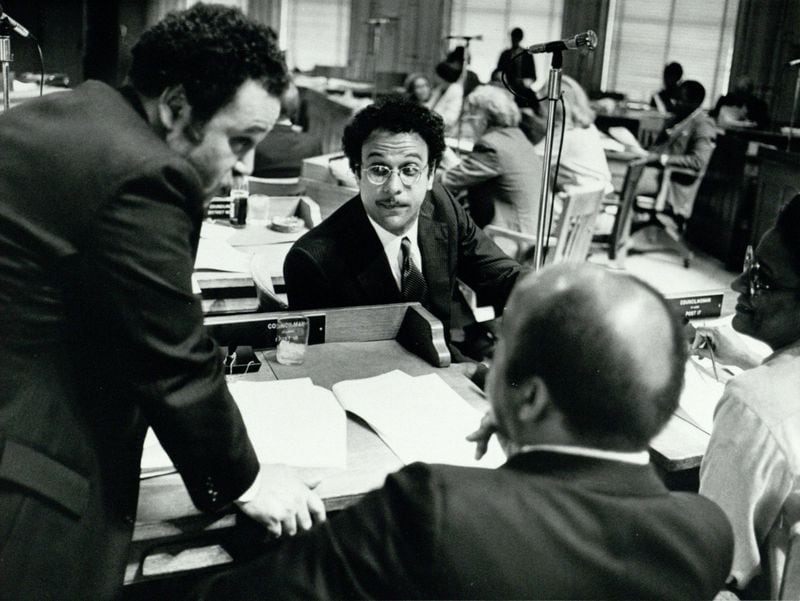

Credit: Jerome McClendon

Credit: Jerome McClendon

Never was that more apparent than in his first year, a period that Lewis described as the “most painful struggle of my five-year career there,” and put him at public odds with Carter and Young.

It was the year of the battle of the Great Park.

The plan was to build the Jimmy Carter Library in a downtown Atlanta park and to construct a four-lane highway to bring visitors there. Lewis opposed the plan from the beginning, arguing it would add to traffic problems, increase the flight of businesses and middle-class residents to the suburbs, alienate tourists and, in the long run, further deprive poor, Black inner-city communities.

“Almost from the first day of council, I got in trouble, what I call good trouble,” Lewis said. “I think it was the first session of council, I introduced a resolution saying that ‘Atlanta will go on record opposing a four-lane road through the Great Park.’ It was passed unanimously by the council, and the mayor signed it,” Lewis said in 1982.

But later, several council members and Young threw their support behind the road, Lewis said. “My feeling is that even before the plan came into being, the mayor had made a commitment to President Carter … that he was locked in and had to tell planners to include the road.”

On a Saturday morning in June of 1982, just days before the vote, Lewis was invited to breakfast with Councilman Ira Jackson at the Canopy Castle on Martin Luther King Jr. Drive.

When he arrived, he was greeted by Young and a small group of council members.

Young put the councilman, his friend, on the spot.

Over eggs, sausage and grits, Young asked that Lewis abstain from voting if he couldn’t support the project.

“There’s no way I can abstain,” he recalled saying to Young. “If I am present, I’m going to vote.”

The next night, at his home, Lewis received a phone call from Jimmy Carter, who said plainly, “I need your help. I really need you to vote for this road.”

Again, Lewis refused, telling Carter: “I’m sorry Mr. President, but I don’t think the road is needed. I made a commitment during my campaign, and I have to stay with that commitment.”

“And with that, my conscience was clear,” Lewis said. “I felt I was on the side of angels.”

Credit: Michael Pugh

Credit: Michael Pugh

At the next council meeting, Lewis, Campbell and Davis voted against the project, which passed, albeit compromised from a four-lane highway to two lanes that would be named Presidential Parkway, later renamed Freedom Parkway.

Young, in 2020 told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution that the Battle of the Great Park was the only time that he and Lewis disagreed on an issue.

“We all ran on a no-roads platform, and that was what you needed to do to get elected,” Young said. “But once I got to be mayor, it seemed to me it wasn’t an option. I apologized to the people, but I broke my pledge because the city was growing so fast that we needed more roads. I agreed with him, but I had another responsibility as mayor. I had to worry about the growth of the city, and I couldn’t imagine turning away President Carter’s library.”

Lewis would write that his stance cost him politically. He was never appointed to an important city council committee and never chaired any committee.

“After I was reelected in 1985, I saw first-term members named chairs of committees all around me, while I still chaired nothing,” Lewis said. “It was almost funny.”

By 1986, Lewis was gone, on his way to Washington for his first stint in Congress.

But the story of the road was not over. In 2017, Dickens created a task force to come up with ways to honor Lewis, who had already been honored by the city with a mural on Auburn Avenue, the John Lewis Plaza in Freedom Park and the John Lewis Invictus Academy, an Atlanta middle school.

Dickens said there was one thing missing — a street. They considered renaming Boulevard after him but didn’t want to force hundreds of residents and businesses to change their addresses.

Finally, Aug. 22, 2018, on the corner of Ponce de Leon Avenue and Freedom Parkway, Lewis pulled a cord to unveil the John Lewis Freedom Parkway.

“We knew his connection to it, in making sure that this didn’t become a superhighway through this city,” Dickens said. “There was a lot of intentionality in our decision. Just like there was a lot of intentionality in everything John Lewis did.”