Wuhan Beat the Virus. Now It’s Moving on by Shutting Out the World.

The city has become a template for the new China, where controlling the narrative is as important as controlling Covid-19.

It’s past 12 on a hot summer’s night in Wuhan, and hundreds of college-age kids are packed into a nightclub called Hepburn, dancing to a mix of Chinese-language Mandopop and American rap. At one point the DJ spins an electronic remix of “My Name Is,” the 1999 hit by Eminem, and the crowd goes wild. Many of the partiers toss fake U.S. $100 bills in the air—even in the age of Donald Trump and the pandemic, American soft power is a potent force—mimicking scenes from music videos.

The club has posted signs urging people to wear masks and keep their distance from one another, but few are doing either. No one sees the need. Wuhan has had just four confirmed cases of the novel coronavirus since May, when the city tested its entire population in the space of two weeks. (All four had traveled from overseas, and were immediately quarantined.) Now, “Wuhan is the safest place in China,” says Hepburn’s deputy general manager, Thomas Tong.

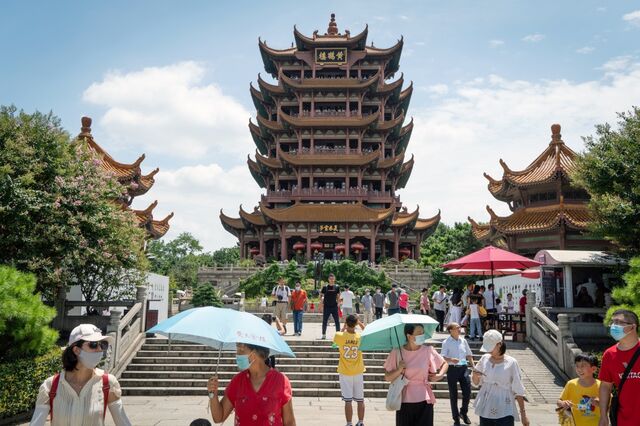

More than eight months after Covid-19 emerged in the industrial hub of 11 million, Wuhan is, perhaps more emphatically than anywhere else, moving into a post-virus future. As the club kids at Hepburn can attest, social life has resumed in all its varieties, with lineups at popular breakfast joints and cinemas and karaoke lounges open for business. Factories and offices are operating normally, although China’s vast surveillance state, partly re-tasked to monitoring public health, has a long reach. A national-ID number is required to purchase fever medicine, and anyone with a high temperature is theoretically required to report it to the authorities. Nightspots aside, people generally wear masks in public, and a system of check-ins has been implemented at most buildings, allowing rapid contact tracing should a case be detected.

The most revealing aspects of life after the coronavirus in Wuhan, however, go beyond the pathogen itself. As President Xi Jinping intensifies repression at home and aggressively pursues Beijing’s claims abroad amid the pandemic, the city is becoming something like a template for the new China, a place with relative economic freedom but intense controls on speech, socially vibrant but isolated from and suspicious of outsiders. Publicly questioning how the government handled the virus is almost impossible, since that would weaken the central rhetorical foundation of Xi’s expanding power: that China’s mighty state conquered a disease that left the U.S., with its raucous democracy and competing centers of power, on its knees. Controlling the narrative, in other words, is just as important as controlling Covid-19.

“China needs stronger nationalism to insulate Xi and his confederates from blame, both domestically and internationally,” said Ian Bremmer, the founder of Eurasia Group, a New York-based political consultancy. In order to promote “confidence that the Chinese model is the correct one,” Bremmer said, the government wants “as much control of the information cycle as possible.”

That task is only getting easier thanks to the Trump Administration, which has made vilifying China its foreign-policy priority in the runup to November’s presidential election. From referring to Covid-19 as the “China virus” to signing an executive order that would effectively ban the popular WeChat and TikTok apps in the U.S., the White House is eager to present the two countries as zero-sum competitors, if not enemies. That’s left many Chinese, who grew up consuming American pop culture and aspiring to study at U.S. universities, wondering whether the world’s other superpower is now irretrievably biased against them, no matter who wins in November.

When Bloomberg News reporters visited Wuhan in April, just as restrictions on daily life were being lifted, the government wanted to portray the city as a success story. Propaganda officials offered to escort foreign reporters on tours of factories that were newly up and running, and temporary hospitals that were about to shut down. Businesspeople were, for the most part, happy to discuss their experiences of the coronavirus and the challenges of keeping employees from getting infected, while trying to resume exports to countries entering their own lockdowns. Ordinary citizens, approached on street corners and in shopping malls, were similarly willing to chat.

During another visit at the end of July, after a period of intensified U.S.-China tensions that included Trump ordering the closure of the Chinese consulate in Houston, claiming it was a center for espionage, the mood had shifted. A resident who’d previously criticized the Chinese government’s management of the virus abruptly canceled a meeting, citing a fear of surveillance. Some companies that had agreed to interviews also backed out, while others said any discussions with reporters for a U.S.-based media organization would have to be arranged through the municipal propaganda department.

Zhang Hai, who attempted to sue the Wuhan government for concealing information after his father died of the coronavirus in January, said police had questioned him twice since May. His account on Weibo, the Chinese social network, has been suspended. “I’m being censored in all kinds of ways now,” said Zhang, who lives in Shenzhen. “My relatives in Wuhan were threatened with losing their jobs” if he continues to speak out, he said.

An official in Wuhan’s municipal foreign-affairs office, Deng Wei, said there are no rules preventing companies or residents from communicating with foreign journalists. But the political atmosphere in China, and the deteriorating relationship with the U.S., have probably reached a point where no formal policy is necessary. In April, the Communist Party formed a task force of law enforcement officials to “defend political security” and “resolve conflicts related to the coronavirus outbreak.” Even academic papers on Covid-19 are subjected to intense government vetting. Meanwhile the government has taken control of the story of Li Wenliang—the Wuhan doctor who was reprimanded by police when he tried to warn peers that a new pathogen was in circulation, and later died from the virus—framing him as a fallen patriot rather than a silenced whistleblower.

To the extent Wuhan’s citizens are willing to discuss the pandemic with visiting journalists, it’s mostly to praise the government’s response—and express shock that the U.S., which many of them are used to admiring, has mishandled it so catastrophically. More than a dozen residents told Bloomberg News that they believed the 11-week quarantine of Wuhan, which began on Jan. 23., was the correct decision, and that continued monitoring is essential. “The government needs to locate everyone’s whereabouts to ensure full containment of the virus,” said a teahouse owner who asked to be identified only by his surname, Hua. “The Chinese government treats citizens like little children by taking good care of them.”

Beijing has relentlessly emphasized a similar message. Propaganda has portrayed the 60 million residents of Wuhan and the surrounding Hubei province as “heroes” for enduring their strict lockdown, a sacrifice that, the story goes, kept Covid-19 from spreading to the rest of China. It’s a narrative that leaves out the first weeks after the virus emerged, when local officials downplayed its severity and avoided reporting new cases during an important Communist Party meeting—allowing travelers from Wuhan to seed international outbreaks—focusing instead on how the central government swept into action afterward.

Photographer: Yan Cong/Bloomberg

Photographer: Yan Cong/Bloomberg

Photographer Yan Cong/Bloomberg

Photographer: Yan Cong/Bloomberg

Photographer: Yan Cong/Bloomberg

Photographer: Yan Cong/Bloomberg

Sound is off

Meanwhile, the country has all but sealed itself off from the world. The number of inbound flights has been sharply restricted, making it difficult even for Chinese citizens abroad to return, and a mandatory 14-day quarantine, under tight surveillance, awaits those who do. State media reports in detail on the chaos the pandemic has caused overseas, contrasting it with the return to normal at home. Not even foreign groceries are above suspicion. After a viral flareup in Beijing was initially linked to fish counters at the capital’s wholesale food market, consumers began shunning imported salmon.

In Wuhan, those willing to be interviewed at length tended to be prosperous residents with some connection to the U.S., whether through work, study, or family. 50-year-old Vivian Lee, who received a green card along with her husband and three children in 2011, agreed to meet at a Starbucks in Xintiandi, an upscale shopping district. Three months earlier the location was takeout-only, and patrons were required to show their “health codes”—green, yellow, or red squares, accessed through a smartphone app, that indicate viral risk—before entering Xintiandi. But on a July evening the neighborhood was packed with people shopping and dining, and no one was really checking. “Now these are just for show,” Lee said, gesturing at a cardboard sign instructing visitors to scan a QR code that would pull up their status.

Lee owns a chain of more than 100 pharmacies in and around Wuhan, and said that if she didn’t need to run the business she’d prefer to return to the U.S., where she thinks life is more relaxed. But, as a place to build a career, “America’s golden age has passed,” she said. Her 24-year-old daughter Xu Yang, who lives in San Francisco and has spent most of the pandemic stuck indoors, feels the same way. “The U.S.,” Xu said by phone, “is no longer a country that offers much tolerance,” or a place where “many immigrants may find a sense of belonging.” She’s planning to return to China as soon as she’s able.

Before the current crisis, Wuhan’s connections to the U.S. had been deepening for decades. The city is an industrial powerhouse at the center of several key rail and road routes, with factories that are crucial parts of global supply chains. Like every other Chinese metropolis, its cinemas and malls are packed with American fare, and many young people grew up watching shows like “Friends” and “The Big Bang Theory,” working on their English in the process. Increasing prosperity allowed many of Wuhan’s citizens to work or study in the U.S., gaining a far greater understanding of American culture and, perhaps, a more skeptical view of China.

Virtually all of those trends have now gone into reverse. With overseas economies in deep recessions and the U.S., along with other Western governments, encouraging companies to reduce their dependence on China, Xi has touted what he calls a “dual circulation” strategy for development in recent weeks. In this model, the domestic economy would serve as the primary driver of demand and growth, and China would tap foreign markets mainly as a source of technology and investment—a situation where “Chinese companies should expect less from the overseas market,” said Yu Zhen, an economics professor at Wuhan University.

At the same time, domestically-produced films and TV shows have become increasingly popular, and are beginning to tackle edgy-in-China subjects like homosexuality, expanding their appeal among younger viewers. And, between the virus and the Trump Administration’s severe restrictions on even temporary immigration, spending time in the U.S. is now a slim possibility for most.

Wuhan’s businesspeople are preparing for the breakdown in ties between the superpowers to hurt both economies. Wuhan Welhel Photoelectric Co. makes helmets and face shields for tasks like welding, with a long list of overseas clients. But now, founder Yao Jun said, American customers are front-loading next year’s orders, fearing that the Trump Administration could escalate from levying tariffs on Chinese goods to actually cutting off imports. In the short term that’s a positive development: Yao has so many shipments to deliver that she’s running her factory around the clock. “But if trade is really disrupted it will be bad news for my business,” she said.

Over a dinner of crayfish, frog legs, and other local specialties, Yao recalled how abandoned she felt on the eve of Chinese New Year in January, when Wuhan was being locked down but state television was broadcasting happy scenes of celebration from around the country. Now, she said, she’s looking on in disbelief at the news from the U.S., incapable of understanding why the world’s most powerful country can’t get the virus under control. “It makes us question whether all citizens really benefit from the freedom and democracy of the American system,” she said.

Yao Daogang, a clean-cut advertising executive in his 40s who was also at the dinner—no relation to Yao Jun—said Chinese people needed to think about the problem from an American point of view. Strict regulations are unworkable in the U.S., he argued, because its citizens would never agree to them. Yao used to travel there regularly to visit friends and family, but said he wouldn’t go now or in the near future, fearful of uncontrolled infections and potential hostility toward Chinese people.

“The fantasy of the U.S. has collapsed, like the heroic images in Hollywood movies,” he said. “The U.S. and China are no longer in a relationship. They’ve moved on to getting a divorce.” —Sharon Chen, Claire Che and Sarah Chen