The Smart Way to Fix the Filibuster

Rather than completely eliminate the procedure, Democrats should reform it so that it continues to exist for truly extraordinary circumstances.

If Democrats get their wish—a landslide victory leading to a Joe Biden presidency, as well as a Democratic Senate and House—they will face an immediate challenge to getting things done. No matter the size of that landslide, the Republican response will be undeterred: a united opposition, akin to a parliamentary minority party, blocking what they can and delegitimizing what they cannot. It will be little different from their approach in the aftermath of the 2008 Democratic landslide. That formula led to huge GOP gains in the 2010 midterm election, and, after Barack Obama’s big reelection victory in 2012, even more gains in the 2014 midterms.

For Democrats facing that obduracy, the biggest challenge will be in the Senate, where the filibuster will be a massive roadblock. Some things, including tax changes and some protection for Medicare and Social Security, might be achievable using the process called reconciliation, which can be done with a simple majority—the same process used to enact the Affordable Care Act and Republican tax cuts. But it is at best an imperfect and limited weapon. Any big plans, such as enacting the John Lewis Voting Rights Act and other democracy reforms, expanding health coverage, and moving toward clean energy, will be dead in their tracks without a change in Senate rules.

But rather than scrap the filibuster entirely, the Democrats may want to instead consider reforming the procedure, so that it continues to exist for truly extraordinary circumstances, but ceases to be the easily deployed blockade it is today. Moreover, this approach would have another advantage, in that adopting it is politically feasible. Here’s why: The outright abolition of Senate Rule XXII—which now requires three-fifths of the Senate, or 60 votes, to pass a law—may be out of reach, even if Democrats win enough Senate seats to have 53 or more of the 100, a net gain viewed as unimaginable six months ago and a heavy lift now. This is because at least three and possibly more Democrats in the Senate have said they are opposed to eliminating the rule. No one is more adamant than West Virginia’s Joe Manchin, but he has company in Jon Tester, Kyrsten Sinema, and Doug Jones.

Of course, minds can change; that is what happened to a slew of Democrats who had long been traditionalists about Senate norms, such as Patrick Leahy, Chris Coons, and Dick Durbin. Even Tester has said that he might rethink his position if the Republicans stonewall everything. But if Democrats cannot find a path to change the rules in some fashion, the opportunities present in the first few months of a new administration, with momentum from a big victory, will dissipate.

What to do? Democrats need a backup plan, something that can get support from those reluctant to eliminate the rule completely and still provide an opening to do big things in the face of a united Republican opposition. Thankfully, there is an alternative.

The current rule in the Senate for legislation is that if a filibuster is conducted, three-fifths of the Senate—60 of the 100 senators—must vote to invoke cloture, which means stopping debate and moving toward a vote on the bill. It is a high hurdle, and the burden is perversely on the majority, not the minority, to overcome the delay. A substantial majority does not guarantee a bill’s passage. Take, for example, the highly popular DISCLOSE Act, which required disclosing the names of big donors to outside groups that pour huge sums anonymously into campaigns, and which passed overwhelmingly in the House in 2009 in response to the Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision, which had opened the dark-money floodgates. The DISCLOSE Act had the support of all 59 Democrats in the Senate but was blocked from becoming law, because every single one of the 41 Republicans refused to support cloture.

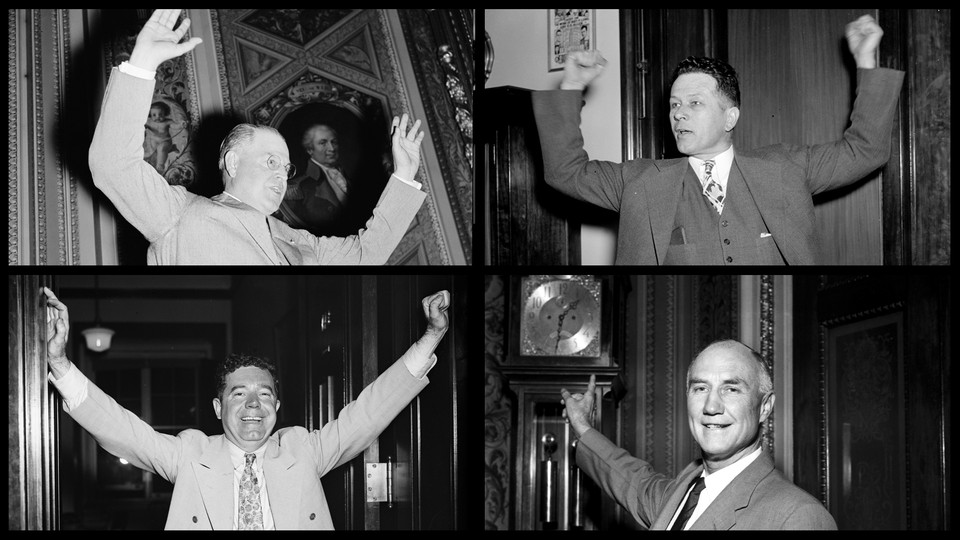

Many Americans associate the filibuster with drama from the civil-rights battles of the 1950s—when the Senate operated around the clock, with senators sleeping on cots set up in the hallways, and votes scheduled for 3 a.m. in efforts to break the will of the minority. But that was when the threshold for cloture was two-thirds of senators present and voting. Under the current rule, by contrast, doing so would be folly. Republicans would not have to show up around the clock—they need only a couple of their members to rotate, to be on the floor to deny any unanimous consent motions and to plague the majority by demanding a quorum call to keep the Senate going, and it would be on the majority to come up with enough votes to do so. Even during the period in 2009–10 when Democrats added their 60th senator, they were stymied on many occasions because one or more of their members was ill or unable to make it to Washington.

The answer is to return the filibuster to its original intention—something to be used rarely, when a minority (not necessarily a partisan one, by the way) feels so strongly about an issue of great national significance that it will make enormous sacrifices to delay a bill. There is a simple way to do this—and, in the meantime, keep Rule XXII and mollify Manchin et al. while also providing an opening for Biden and his Democrats to get big things done. That is to flip the numbers: Instead of 60 votes required to end debate, the procedure should require 40 votes to continue it. If at any time the minority cannot muster 40 votes, debate ends, cloture is invoked, and the bill can be passed by the votes of a simple majority.

This change will preserve a unique feature of the Senate, preventing it from becoming just a smaller House of Representatives. It will not allow Democrats to pass everything they want. But it will stop the filibuster from standing in the way of necessary, broadly popular initiatives. If, for example, Democrats introduced a sweeping package of democracy reforms and Republicans filibustered them, the majority could keep the Senate in session around the clock for days or weeks and require nearly all the Republicans to be present constantly, sleeping near the Senate floor and ready on a moment’s notice to jump up and get to the floor to vote—including those who are quite advanced in years, such as Jim Inhofe, Richard Shelby, Charles Grassley, and Mitch McConnell. It would require a huge, sustained commitment on the part of Republicans, not the minor gesture now required. The drama, and the attention, would also give Democrats a chance to explain their reforms and perhaps get more public support—and eventually, they would get a law. A bolder option would be to raise the minority threshold to 45 votes required to continue debate, instead of 40.

The destruction caused by Donald Trump and his Republican allies in Congress, to our health, environment, economy, and political system, is unprecedented. Undoing it will not be easy no matter the rules or the political composition of Congress. But changing the rules in the Senate is a necessary, if not sufficient, requirement to making progress. Fortunately, there are options besides complete elimination of the filibuster rule.

This story is part of the project “The Battle for the Constitution,” in partnership with the National Constitution Center.