As historic statues are torn down or questioned across America, Frank Gehry, one of the world’s leading architects, has declared an end to the age of bombastic “great man” monuments.

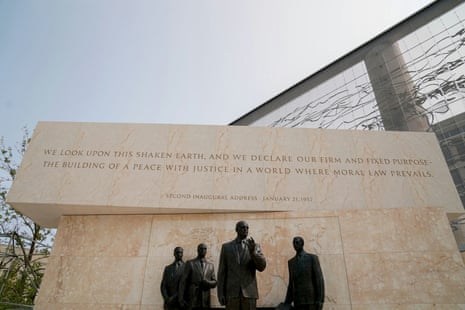

To illustrate the point, Gehry’s $150m tribute to Dwight Eisenhower, second world war general and 34th US president, includes a bronze sculpture of Eisenhower as a boy, statues of young soldiers and an African American presidential adviser, and a stainless steel woven tapestry depicting the Normandy coastline.

The memorial, in a four-acre park near the US Capitol in Washington, will be dedicated on Thursday at a time when racial unrest has prompted the removal of numerous statues of Confederate soldiers who fought to uphold slavery and debate over those commemorating former presidents such as Thomas Jefferson, Andrew Jackson and even Abraham Lincoln.

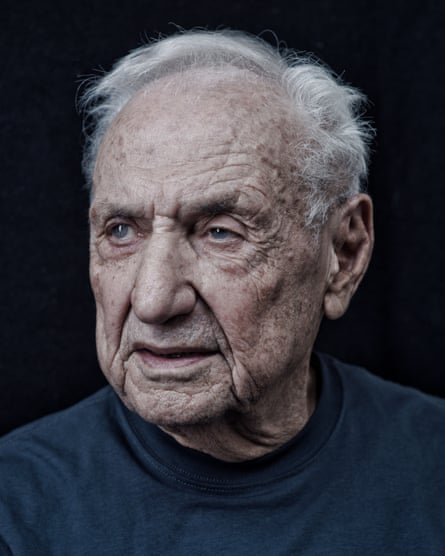

“I think the statues going up are fairly modest compared to the ones coming down,” Gehry, 91, tells the Guardian by phone from Los Angeles. “And the ones coming down are part of a different ethic and time. Eisenhower was a giver of his life and time for the community and the world at large, so it’s not bombastic and it’s trying to be more modest.”

He adds: “We’re in the middle of traffic, a lot of buildings around it, so the tapestry is an attempt to organize the site, and the sculptures are meant to sit in the garden and tell about his two great accomplishments. One is General Eisenhower, who won the war. The other is president of many accomplishments, including civil rights, highways and healthcare. The education department behind the tapestry attests to his interest in that topic. So I think it’s more of a story about what he did and not a bombastic story about ‘Look, here I am’.”

Gehry points to Maya Lin’s minimalist Vietnam war memorial, which has the names of more than 58,000 dead or missing service members inscribed in polished black granite, as evidence of a move beyond the idiom of heroic statues celebrating dead white males. “Maya Lin showed us the way with the Vietnam memorial. It’s modest. It tells a story, and I think that’s what we were trying to do,” he said.

Dozens of Confederate statues have been taken down in the wake of this year’s Black Lives Matter protests following the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis. For many, the statues are a constant reminder of the slave-owning south, erected long after the war in a bid to reassert white supremacy. Although “we don’t have to destroy the past”, Gehry says, he understands the need to remove them.

“If we’d gone on from it and solved the problems, then I think it’s less onerous to say, OK, that happened in the past and look where we came. But we haven’t. It’s a thorn in somebody’s side, in our side, to have them sticking out at us.”

Earlier this month a taskforce commissioned by the Washington DC government recommended renaming, relocating or adding context to many monuments, buildings, parks and schools because of their namesakes’ involvement in slavery or racial oppression. The Washington monument and Jefferson memorial were among the targets, triggering a fierce critical backlash.

Gehry does not want to go there. “Oh, my God, I’m not able to make that kind of leap. Different place, different time. Again, if we’d solved all the problems, it would feel differently. At least a little bit of anxiety is still there because we haven’t completely solved it. It’s up to us to do that.”

Gehry, who was born in Canada and served in the US military, is revered for breathtaking buildings including the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, the Dancing House in Prague and the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao in Spain. But with the Eisenhower project, authorized by Congress in 1999, he collided with the unique frustrations of Washington as members of Congress, interest groups, historians and family members all had an opinion about a fitting memorial to the supreme allied commander who crushed the Nazis.

Susan Eisenhower, “Ike’s” granddaughter, raised objections to Gehry’s original design during a congressional hearing in March 2012. “Symbolism will also play a vital non-verbal role in capturing the essence of Ike’s contribution, but we’ve heard from many people in the last months who have objections to the 80-foot metal mesh so-called ‘tapestries’,” she said. “Despite the Eisenhower memorial commission’s references to this ancient tradition, modern tapestries have generally been found in the communist world.”

Gehry was warned from the beginning that it would be tough to please everyone. “If we had done anything there would have been pushback from some of these entities,” he reflects philosophically. “I’m sure there’s people out there now that would love to see it all torn down and become a classical monument. I think that’s not the way to go. We’re not in a classical period. We can learn from classicism but we can’t copy it and, when we do, it’s to our negative.”

After years of acrimony and wrangling, James Baker, the former secretary of state, mediated a compromise and Gehry made changes to the design that satisfied the family. But given the current political climate, Eisenhower, president from 1953 to 1961, is not the most obvious choice for a new piece of public art. He hailed from small town Kansas in the conservative heartland, personified a decade dominated by white men and was a staid Republican whose vice-president was Richard Nixon. He signed an executive order that banned gay and lesbian people from working for the federal government.

The memorial’s dedication will be hosted by Bret Baier, chief political anchor of Fox News, a network notorious for its close relationship with Donald Trump’s White House. Gehry himself is unable to travel to the event due to the coronavirus pandemic.

But Eisenhower also enacted the first civil rights legislation since Reconstruction, appointed the supreme court chief justice who issued the Brown v Board of Education ruling that desegregated public schools and sent 1,200 paratroopers to Little Rock, Arkansas, to escort Black students past a hostile white crowd. The memorial sits cheek by jowl with three government departments he created – education, health and the Federal Aviation Administration – as well as the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, which is fitting for the father of Nasa.

It is a complex legacy. If protesters target this site after it opens to the public on Friday, Gehry will not object. “He fought for our right to protest so, I guess, bring it on.”

Gehry received the presidential medal of freedom from Barack Obama in 2016 and recalls meeting Joe Biden at the ceremony. Asked if he hopes Biden becomes the next occupant of the White House, Gehry says: “Yes. Emphatically yes.”

And perhaps one day an architect will be asked to design a memorial to Trump? The nonagenarian remarks drily: “Somebody else would do it.”