What Happens When NYC’s Taxis Have No Passengers

Some 10,000 drivers are delivering millions of free meals instead.

Drivers are drinking coffee. Drivers are sleeping. Drivers are listening to the radio, smoking, and chatting under the early morning streetlights, waiting in a line that stretches along a once-busy street on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. The first driver took his place at 3:30 a.m. on this August day. At about 8 a.m., he and few dozen others in line will move to a nearby parking lot on the East River and start loading their yellow cabs and private cars with boxes of free food. Then they’ll hustle out to hungry people across the five boroughs of New York City, deliver the meals, and return for more. They’ll each make $53 per route, a few hundred dollars a day if they hurry. Most days they don’t earn as much as they would with passengers, but “it’s better than nothing,” says Faisal Tawfiq, a driver from Ghana.

THOMAS JUNG, 67

Sound is off

The Covid-19 pandemic was catastrophic for New York City cabdrivers. Some were already in debt because of predatory loans; most were still adjusting to the competition from Uber and other ride-share services. Then, in a matter of weeks, demand for taxi and for-hire rides dropped 84% from pre-pandemic levels, according to a recent report from the Taxi & Limousine Commission. Drivers described cruising a desolate Manhattan for hours without picking up a single fare.

AKRAM CHANCHANE: “We are happy because we feel like we are helping people survive. Some of them are in very bad condition, they can’t walk, they can’t go to the store. A lot of the people give us water because they see we are sweating. They really appreciate it.”

ALEX ZERELLI (LEFT) & AKRAM CHANCHANE (RIGHT), BOTH 44

Sound is off

Meanwhile, the spreading virus created a potential crisis for the thousands of people who couldn’t leave their homes to get food. TLC Commissioner Aloysee Heredia Jarmoszuk came up with a plan to help both the idling drivers and the homebound New Yorkers. “I pitched the idea of using TLC drivers because they were going to be in need of work, they are background checked and deemed essential,” Jarmoszuk says. “They were an ideal workforce, hardworking, professional drivers who are vetted.”

JOSELITO MATAILO, 42 (WITH ERICA LICEA, 41)

Sound is off

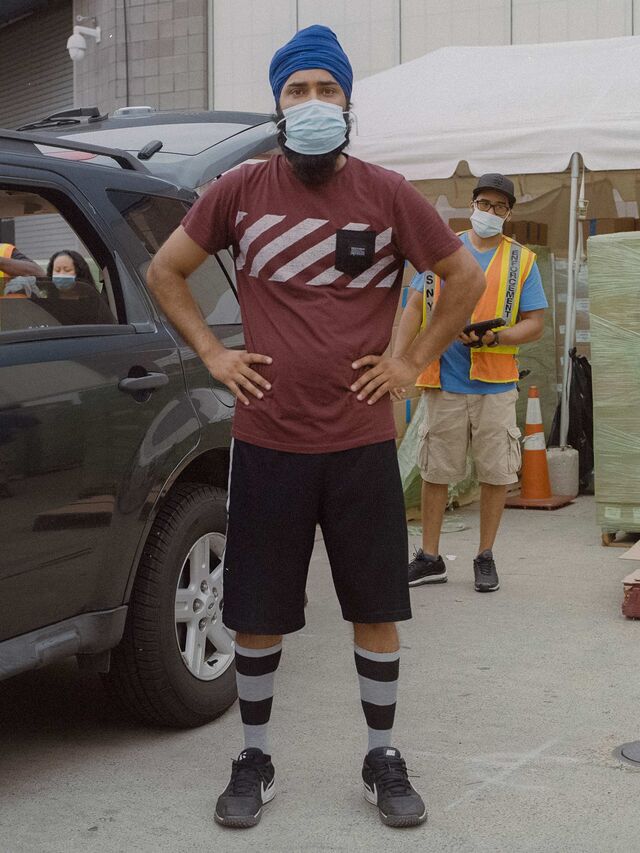

TARLOCHAN SINGH, 25

Sound is off

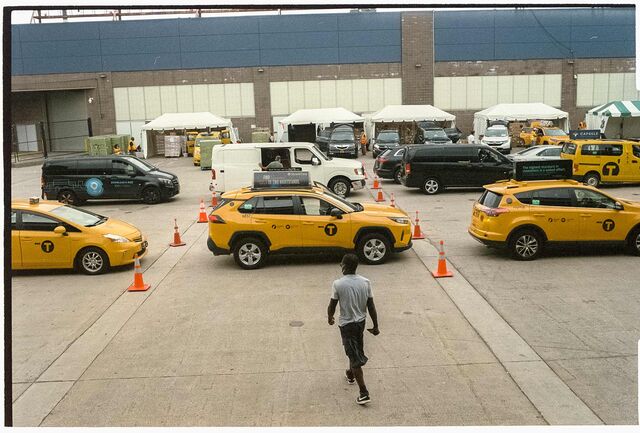

The result was the GetFoodNYC emergency home food delivery program, which is funded by the city and has paid around 10,000 drivers about $35 million for delivering more than 64 million meals to homebound New Yorkers since March. The drivers line up near a half-dozen loading sites around the city and wait for National Guard soldiers and city sanitation workers to load their cars with big brown boxes that each hold nine meals. Some drivers have a baby in the back seat; others pack their small sedans to the roof. “For me it’s more safe, that’s the important thing,” says another driver, Claudia Salazar. “Maybe sometimes I only get a hundred dollars. That’s better than the risk.”

Some interviews have been condensed.