With less than six weeks to go before Election Day, and with over 250 COVID-related election lawsuits filed across 45 states, the litigation strategy of the Trump campaign and its allies has become clear: try to block the expansion of mail-in balloting whenever possible and, in a few key states, create enough chaos in the system and legal and political uncertainty in the results that the Supreme Court, Congress, or Republican legislatures can throw the election to Trump if the outcome is at all close or in doubt. It’s a Hail Mary, but in a close enough election, we cannot count the possibility out. I’ve never been more worried about American democracy than I am right now.

Much of the blizzard of election litigation concerns the casting of ballots by mail, a means of voting that has exploded thanks to COVID-19, and the fears many people have of voting in person during a pandemic. Rules for casting mail-in ballots vary from state to state, and some are onerous during a pandemic, such as a requirement to have an absentee ballot notarized. There are also serious questions about timing; even without all the tumult at the United States Postal Service, some states allow voters to request absentee ballots in the period close to the election, and there is real fear that voters will not get their ballots back in time to elected officials to be counted. Some state and federal courts have responded to these lawsuits by relaxing technical requirements, such as allowing ballots to be counted if they arrive after Election Day so long as they are postmarked by Election Day (or if they arrive shortly after Election Day with no postmark, given that USPS does not always put a postmark—or a legible one—on ballot envelopes).

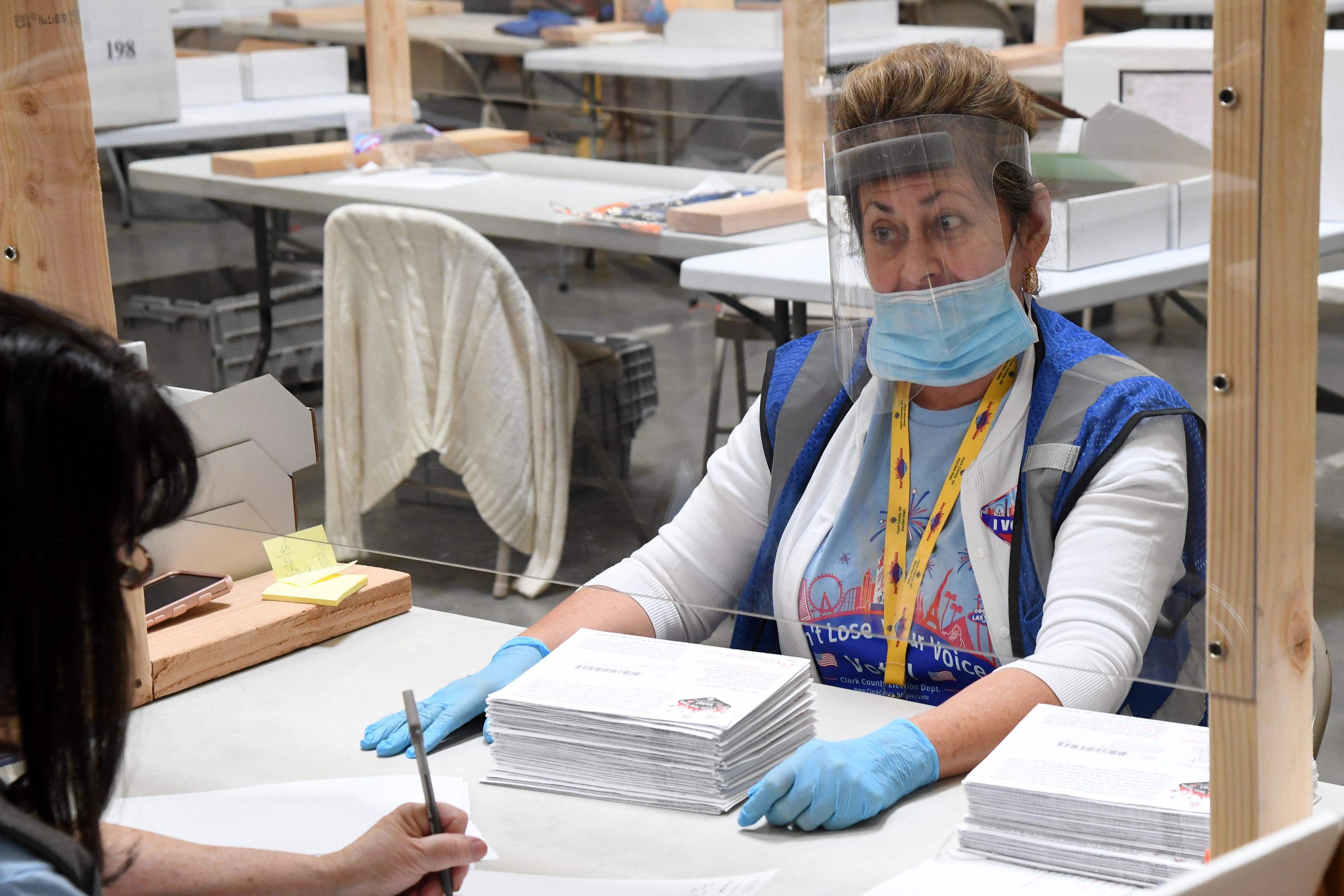

Trump has made repeated and loud unsubstantiated claims of widespread voter fraud in relation to mail-in ballots, even though he and his allies have voted by mail themselves and even as the campaign has begun encouraging more mail-in balloting among his own supporters. The Trump and Republican litigation strategy has been to fight efforts to expand voting by mail: They have opposed expanded use of government drop boxes to return absentee ballots, extension of deadlines for ballot return, and state decisions to proactively send mail-in ballots to all active registered voters. Four states—California, Nevada, New Jersey, and Vermont—are doing so this time, joining the five other states that already conduct their elections almost exclusively by mail. The Trump campaign has through litigation attacked the expansion of mail-in balloting in Nevada, so far unsuccessfully, and Attorney General William Barr has ridiculously claimed that election officials—led by a Republican secretary of state—will somehow “find” 100,000 ballots to help Joe Biden win the state if Trump is in the lead.

The Trump strategy of fighting the expansion of mail-in balloting appears to be twofold. To begin with, the campaign appears to have made the calculation that lower turnout will help the president win reelection. This may explain why Pennsylvania Republicans are planning on going to the U.S. Supreme Court to argue against a state Supreme Court ruling allowing the counting of ballots arriving soon after Election Day without a legible postmark. They argue that doing so unconstitutionally extends Election Day beyond Nov. 3 and takes power away from the Pennsylvania Legislature to choose presidential electors.

The first argument is not a particularly strong one: A decision to accept ballots soon after Election Day without a legible postmark does not extend Election Day as much as it implements how election officials determine if a mailed ballot was timely mailed. It recognizes the reality that many ballots have been arriving without postmarks and uses proximity to the election as a proxy for timely voting. Virginia and Nevada recently adopted similar rules, in light of pandemic-related mail delays. The Trump-allied Honest Elections Project is fighting a consent decree over a similar extension in Minnesota.

The argument about the state Supreme Court’s ruling usurping legislative power to set federal election rules echoes a parallel claim that was made during the disputed election in 2000. The question is whether a state supreme court usurps legislative power when it interprets election rules in line with both state statutes and the state constitution. The argument that a state supreme court applying a state constitution in a voting case usurps legislative power is weak to me, but it was convincing enough for the more conservative members of the Supreme Court that decided Bush v. Gore.

The fighting over things like postmark rules are fights on the edges, the kind of trench warfare that will only matter if the election comes down to hundreds of ballots in a key swing state essential for the Electoral College outcome. But there’s a second play here as well, one that is far more worrisome.

The idea is to throw so much muck into the process and cast so much doubt on who is the actual winner in one of those swing states because of supposed massive voter fraud and uncertainty about the rules for absentee ballots that some other actor besides the voter will decide the winner of the election. That could be the RBG-less Supreme Court resolving a dispute over a group of ballots. Indeed, on Tuesday, Vice President Mike Pence suggested that Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s replacement needs to be seated, possibly without so much as a hearing, in order to decide “election issues [that] may come before the Supreme Court in the days following the election,” including questions involving “universal unsolicited mail” and states “extending the deadline” for ballot receipt. (Never mind that a 4–4 split on the court on an election issue is unlikely.) It could be a Republican legislature in a state saying it has the right under Article 2 of the Constitution to pick the state’s winner in the face of uncertainty. Bart Gellman in the Atlantic recently quoted a Republican operative imagining these state legislatures saying, “All right, we’ve been given this constitutional power. We don’t think the results of our own state are accurate, so here’s our slate of electors that we think properly reflect the results of our state.” And it could be Republicans in the Senate—if they keep their majority—not counting Electoral College votes that were cast for Biden based upon manufactured uncertainty. This would lead to a dispute with the Democratic House and lead to a political struggle over the presidency.

The president has been laying the groundwork for these claims for months, and just Tuesday his son, Donald Trump Jr., baselessly suggested that Democrats will “add millions of fraudulent ballots that can cancel your vote and overturn the election.” (The video remains up on Facebook even though it contains blatant election disinformation. Facebook has added a label to the post, however.)

If we are lucky enough, the election will not be close, and we will avoid this election meltdown only to start panicking again in the run-up to 2024. But if it is close, all bets are off.

We should not think of the litigation and the wild claims of voter fraud as separate from one another. Instead, they are part of a play to grab power if the election is close enough. There are good legal arguments against a power grab, but if another body tries to overturn the will of the people in voting for president, there will be protests in the streets, with the potential for violence.

This is a five-alarm fire, folks. It’s time to wake up.