The Limits of Desegregation in Washington, D.C.

Hugh Price and his family fought for him to be one of the first Black students at his all-white high school in Washington, D.C. But once he was there, he “couldn’t wait for it to be over.”

Editor’s Note: This is the first story in The Firsts, a five-part series about the children who desegregated America’s schools.

Hugh Price can recall only a few exceptions to the rigid segregation of the city he was born into on November 22, 1941. One was right down the street. Raymond Elementary was a long, red rectangle of a building that was a short walk from his home on New Hampshire Avenue, in Washington, D.C. Price always looked forward to participating in the after-school parks-and-recreation program there. But Raymond was an all-white school, so he could not attend during the day. Instead, he went to Blanche K. Bruce Elementary, the school for Black students not far away.

Sitting with me at the dining-room table in his home in New Rochelle, New York, in October 2019, Price recalled the “wall of segregation” in the city. He could go to the roller-skating rink on the street level of Kalorama Road, but the bowling alley in the rink’s basement was off-limits. He was not allowed to watch Westerns in the movie theaters on the other side of 14th Street. He couldn’t go on the rides at the amusement park on the outskirts of the city.

But the community he came from was strong: He grew up in the orbit of Howard University, and both his parents, Kline and Charlotte, were graduates of the storied historically black college. Their home was a brisk 15-minute walk up Georgia Avenue from their alma mater. Many of the teachers at his elementary school were alumni as well. The family called some of the titans of the civil-rights movement friends and neighbors. Charles Hamilton Houston, who transformed Howard’s law school into the greatest producer of civil-rights lawyers in the country, lived a stone’s throw down the street. Sam Lacy, the sportswriter who persuasively pressed the case for integrating professional baseball, at The Chicago Defender and the Baltimore Afro-American, did too. “That village was working,” Price told me. “Everybody knew everybody.”

Being surrounded by such luminaries, and embracing the ethos of Howard—“Go through the barriers, tunnel underneath the barriers, go around the barriers, go up over top,” as Price put it—deeply influenced his parents, especially his mother. In 1947, she supported activists and parents who protested outside schools in the city. And she was a financial backer of the Consolidated Parent Group—a coalition of Black residents in D.C. who were fed up with the inadequacies of the educational facilities for Black students—which aggressively sued the city. From her vantage point within the movement, she saw desegregation coming.

In 1953, after Price completed elementary school, the family moved to a house off 19th Street in Northeast D.C., a block away from Taft Junior High School, which his parents hoped he would integrate. But first, like other Black parents who wanted their children to experience desegregated spaces (and could afford it), they sent him to the private, integrated Georgetown Day School, which was clear across the city. His stay there turned out to be brief.

On May 17, 1954, less than a year after Hugh enrolled at Georgetown Day, the Supreme Court remade America when it unanimously decided in Brown v. Board of Education that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” But another decision handed down that day was the one the Prices really cared about. In Bolling v. Sharpe, the Court heard arguments that the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal-protection clause—used to justify the Brown decision—did not apply to Washington, D.C., because it was not a state. But the Court ultimately ruled that the Fifth Amendment’s guarantee of “liberty” meant that the federal district had to desegregate anyway.

A day after these decisions, Dwight Eisenhower summoned the city’s commissioners to the White House. The president wanted the capital to chart the path for the nation on desegregation. Any hiccups in the desegregation of D.C. could send the wrong signal to southern states and set progress back by years. A week later, the superintendent of the city’s schools, Hobart Corning, came back with a plan: gradual integration in two waves of students. The first wave would be small. Local leaders roundly criticized the plan and argued that Corning, as the historian Jason Morgan Ward has put it, “cared more about placating anxious local whites than ensuring educational equality.”

Still, practically, Corning’s plan meant that the first Black students to integrate the public schools would do so that September. The “firsts” would be those students who had not gone to the district’s public schools the year before—students who had moved in from another area, and students from private schools. Students like Hugh Price.

“I

t was a little tense,” Price told me. He was thinking about the times white students used him and his classmates as punching bags.

At Taft Junior High, in 1954, Price’s eighth-grade teacher thought it might be a good idea to have the Black students serve as hall monitors. The once all-white school had just integrated, and there were 26 Black students, including Price, in a student population of more than 850. They became easy targets when they were in the halls between classes. White students would hit, nudge, and poke them as they passed by. Aside from those slights, however, Price said, the first week of integration of the public schools in the nation’s capital went off without much of a hitch.

Then white families realized that more Black students might soon be coming.

The relative success of integration had given Corning confidence. A week into the fall semester, the superintendent announced that he would be speeding up the integration process and asking students who had been in the D.C. public-school system the year before—and who attended segregated schools—if they would like to attend schools closer to their homes. That hadn’t been the original plan, but the ease with which the schools had desegregated so far seemed promising.

Integration opponents quickly barked their opposition. “Can we afford to use children’s lives in a sociological experiment which adds nothing to the advancement of the Negro race?” the president of the D.C. Federation of Citizens Association, an anti-integration group in the city, asked during a school-board meeting. Two weeks later, on October 4, as the second wave of Black students began arriving at white schools, white students began walking out of classrooms.

The first boycotts happened at the high schools. Groups of students—500 at Anacostia High and 150 at McKinley High—demonstrated outside the buildings. Charles Bish, the principal of McKinley, tried to calm the protesters, but found little success. “We had such smooth sailing in the first three weeks [of school] we thought we were doing better than we were,” Bish told faculty members later that day, according to Washington Post reports at the time.

The unrest that was brewing was anything but a model for other school districts across the country, as Bryant Bowles, a 34-year-old segregationist who had assisted integration walkouts in Delaware and Baltimore, joined the demonstrators. Several students from other local schools joined the protests the next day. But as white students at Taft prepared to play hooky, they did something peculiar.

“A number of my white classmates came up to the handful of Black students who were there and said, ‘We’re going to go boycott this integration of the school. Come join us,’” Price told me. He laughed. He’s still puzzled about it. “We’re like: ‘Have you lost your minds?’”

Corning had to find a way to get truants back into classrooms. On October 7, he declared that any students who continued to protest would forfeit the right to take part in school activities such as band, sports, or theater for the rest of the year. Most of the students were scared straight, and nearly all of them returned to class the next day.

A Washington Post editorial described the return to school simply: “Back to Sanity,” the headline read.

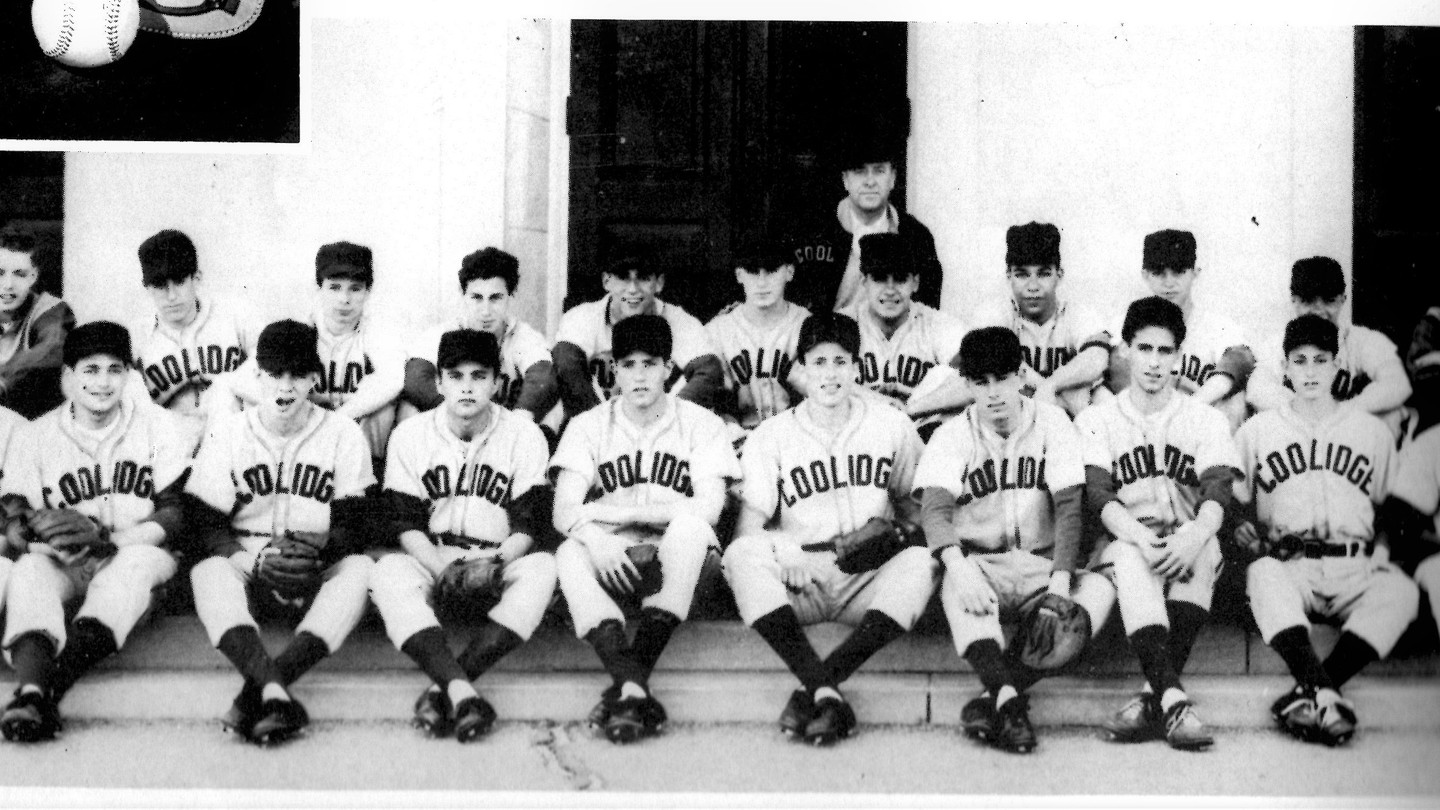

After Price completed ninth grade at Taft, he had a choice. He could go to the school he was zoned for, McKinley High, where several of his Black classmates from Taft were going; he could go to prep school, as several other affluent Black children were doing; or he could attend Coolidge High, which offered several classes McKinley did not, including German. He decided against going to prep school, because he thought he would miss the social life of the public schools. The additional classes at Coolidge made the choice easy.

His experience at Coolidge was similar to what he’d found at Taft. Black enrollment at the school hovered around 5 to 8 percent initially, by his estimation. He rarely socialized with his white classmates. His time there was “not strained, but it wasn’t really open and accommodating,” he said.

D.C. had started to change. White families began fleeing neighborhoods that Black families had moved into. Taft Junior High, which was overwhelmingly white when the Prices moved into the neighborhood, had become overwhelmingly Black in the span of four years. “There were moving trucks that came up every day, and white families just scattered,” Price said. They ran to the suburbs in Prince George’s County, Maryland, and Alexandria, Virginia. A segregationist tabloid in Alabama cartoonishly outlined the white flight from D.C. in a poem:

They’re jumping out the windows,

They’re tearing down the doors,

They’re headed for Virginia,

By twos and threes and scores.

If the district was supposed to be a model—to send a message about the ease and benefits of integration—it was failing.

There were a few positive moments in Price’s time at Coolidge. He was elected vice president of his class, joined the government club, and made the baseball team his senior year. “But there wasn’t any [integrated] socializing,” he said. “Basically, when the school day was over, if you weren’t there for a club or whatever, you just headed home.” For Black students, there were no gatherings with white students at the movie theaters or the bowling alleys. Price’s teachers were friendly and supportive, but the guidance counselors, including several holdovers from the time when schools were segregated, “did not have all of the students’ best interests at heart.”

During the summer between his junior and senior years, he was given an aptitude test to assess his potential. “I was told—and I will never forget this—that I probably would get to go to college, but that I should not count on going to graduate school or professional school. And that seared into my brain. It really shook me.” He told his parents what had happened. They calmly reminded him of his community. The network of elders at Howard. The teachers, physicians, and lawyers he’d grown up around. Go through the barriers, tunnel underneath the barriers, go around the barriers, go up over top.

Overall, the three years he spent at Coolidge were ample preparation for everything that was to come. “It was three years of just sort of hunkering down and getting through it. And I couldn’t wait for it to be over,” he said. “I couldn’t wait to leave town.”

After high school, Hugh Price became one of five Black people in a 250-person graduating class at Amherst College in Massachusetts. He was a marshal at the March on Washington in 1963. He went to Yale Law School, served on the editorial board of The New York Times, and led the National Urban League, one of the nation’s premier civil-rights organizations, from 1994 to 2003. But he still thinks about the test that told him he should not expect much from his life. “That was my introduction to the fallacious and racist application of testing to hold kids back,” he told me.

As our conversation wound to a close, I asked Price what his experience in high school taught him about the limits of integration—particularly as schools across the country have resegregated. “The whole point of the civil-rights movement and the Brown decision was to say that you can’t deny me certain opportunities and privileges based on my race,” he said. “I think it was rightly assumed that once the barriers were removed, that society would become integrated. And that happened to some degree.”

But segregation by residential patterns persists, disparities in testing persist, and inequitable schooling persists. In D.C., several of the high schools where white students protested to keep Black students out—Coolidge, Anacostia, McKinley—now enroll almost no white students. “That’s why we have these very intense fights now,” Price said.