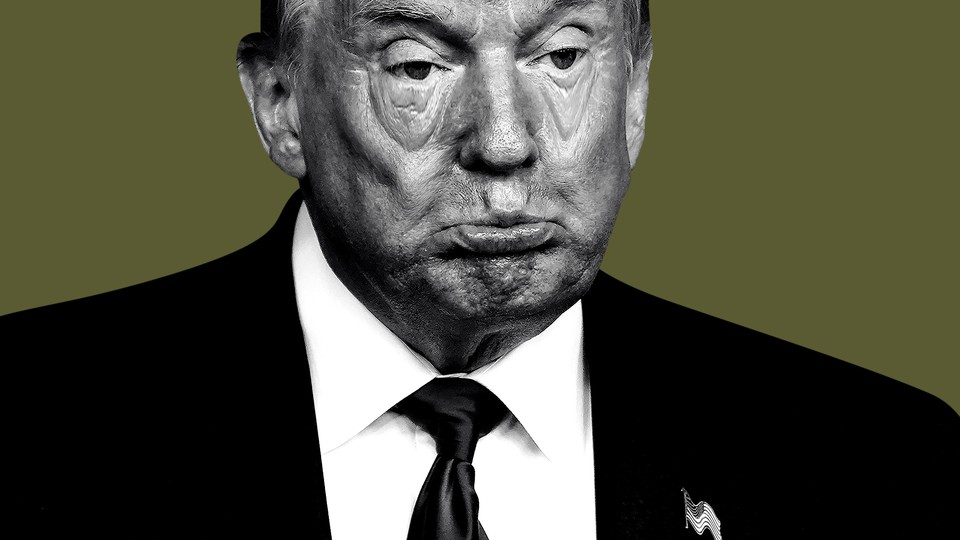

The Tedium of Trump

No matter how many crazy things happen, the fundamentals are the same: The president is a greedy racist and misogynist who does not understand his job.

Donald Trump has built his public persona around the central importance of grabbing attention—whether his actions provoke delight or fury. And yet he is, and has long been, boring.

Four years into his presidency, Trump isn’t boring in the way a dull, empty afternoon is boring. Trump is boring in the way that the seventh season of a reality-television show is boring: A lot is happening, but there’s nothing to say about it. The president is a man without depths to plumb. What you see is what you get, and what you get is the same mix of venality, solipsism, and racial hatred that has long been obvious. Trump’s abuses of the presidency are often compared to those of Richard Nixon, but Nixon had a deep, if troubled, interior life; one biographer characterized Nixon as struggling with “tragic flaws,” a description hard to imagine any credible biographer using to describe Trump. In a democracy whose vitality depends, at least in part, on what people are paying attention to and what they think about it, the frenzied monotony of Trump raises the question: What happens when politics is crucially important, but there is little original to say?

The fact that pundits may have a tough time concocting original commentary is not, in itself, the country’s biggest problem. But at its best, the work of people who write and talk and make art about politics is valuable because it helps other members of society make sense of their shared world. If that work loses depth or relevance, democratic culture in the United States diminishes, and people who otherwise would be engaged with politics turn their attention elsewhere.

It’s not that nothing is happening. With Election Day only a month away, Trump has repeatedly refused to commit to a peaceful transfer of power and is doing his best to cast doubt on the integrity of the vote, calling mail-in ballots “a whole big scam.” He is now poised to fill his third seat on the Supreme Court following the death of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, a victory that would tilt the politics of the Court rightward for a generation. Throughout his presidency, he has arguably committed dozens of impeachable offenses during his time in office, from firing FBI Director James Comey and attempting to fire Special Counsel Robert Mueller to promising pardons to Department of Homeland Security officials if they turned away asylum applicants at the border to doling out a commutation to his associate Roger Stone, seemingly as a reward for Stone’s refusal to testify against Trump during the Russia investigation.

But while these scandals are important, they also are in some ways the same story: The president is a greedy racist and misogynist who does not understand his job. “Is it technically news if he’s doing his usual racism?” pondered the Daily Beast reporter Asawin Suebsaeng after Trump let loose a particularly vile screed against Representative Ilhan Omar during a rally this month. Even Trump’s disturbing threat not to concede is a replay of his insistence in October 2016 that he would accept the results of the upcoming election “if I win.”

Read any of the tell-alls written by Trump’s former close associates or family members—not to mention journalists such as Bob Woodward—and you will come away with basically the same understanding. As the journalist Jennifer Szalai wrote in her New York Times review of Woodward’s latest chronicle of the Trump administration, “The Trump that emerges in ‘Rage’ is impetuous and self-aggrandizing—in other words, immediately recognizable to anyone paying even the minimal amount of attention.”

There is something uncanny about this. The English novelist E. M. Forster argued that the difference between a fictional character and a real person is that it is possible to know everything about a character in a novel; real people, however, see one another through a glass, darkly. And yet while it may not be possible to know every hidden detail of Trump’s life, it is trivially easy to understand everything about his personality. If he were a character, Forster would call him flat, unrealistic: He does not, as Forster requires, have the capacity to surprise. At some point over the course of the Trump era, this became a running joke among political commentators, who, every time Trump does something appalling and yet obvious, make cracks on social media about how hackneyed the Trump presidency would seem if it were fiction.

This has created a problem for artists as well. Surveying the landscape of anti-Trump art in February 2019, the cultural critic Jillian Steinhauer argued that the work had failed to hit the mark: It was missing, she wrote, “the critical introspection to accompany the laughter.” But such introspection is hard to achieve when the person prompting it is so lacking in depth or interiority.

Likewise, four years into this presidency, uncovering fresh insight into Trump or his administration is difficult. Activists, journalists, and commentators found those insights earlier on. Use of the phrase The cruelty is the point, coined by The Atlantic’s Adam Serwer in 2018, has become widespread in part because it continues to be uncomplicatedly true: A lot of the time, the motivations of Trump and those around him are not actually more involved than a desire to hurt others. The idea is so simple that it’s more or less become a meme, which isn’t to deride its perceptiveness but rather to say that the Trump White House is fundamentally simple. Personally, I wrote a great deal in the first few years of the administration about Trump’s understanding of law as a cudgel against the vulnerable before it dawned on me that I was writing the same article over and over again.

This leaves two main options for those analyzing and writing about politics. One is to shrug and accept that the times may merit writing the same thing over and over again. The country is in the midst of an emergency; what does it matter if the emergency is repetitive? Sometimes yelling loudly enough, and for long enough, can move the relevant political figures to act—as it did in the case of impeachment.

But the danger is that, by yelling, the speaker becomes part of the great roaring Trump media machine, the engine of which is dependent on the indignation of the president’s opponents as much as the president’s own vileness. “There is no such thing as Trump fatigue,” the journalist Sopan Deb said when news of John Bolton’s book broke in January. “There will always be Trump books sucking up oxygen and authors to make money off them.” The same could be said of the fleet of commentary launched by Bolton’s book and all the books like his, Woodward’s among them. Along these lines, the opinion writer Drew Magary announced recently that he was stopping his column out of exhaustion with the “hamster wheel” of political commentary: “I have nothing left to say beyond what I’ve already said.”

That leaves the option of taking a step back from politics and finding intellectual engagement elsewhere. “It may be enough to cultivate your own artistic garden,” Margaret Atwood wrote after Trump’s election, suggesting that artists and writers find their footing in exploring common humanity: “Lives may be deformed by politics—and many certainly have been—but we are not, finally, the sum of our politicians.” Atwood struck a hopeful note, but this instinct can also manifest as something more parochial, a turning inward rather than an effort to expand one’s horizons beyond the events of the day. In 2019, Venkatesh Rao began writing on his blog Ribbonfarm about what he saw as an emerging aesthetic of home goods and fuzzy socks as a refuge from political tempests: “Domestic cozy,” as he called it, is “something of a pre-emptive retreat from worldly affairs for a generation that, quite understandably, thinks the public sphere is falling apart.” The comfort of a weighted blanket can be a shield from political engagement as well as other people.

This has a historical echo with the later years of the Soviet Union. In the 1970s and ’80s, many Soviet citizens—among them young people, writers, and artists, the sorts of people one would expect to be engaged in political life—pulled away from politics, which seemed to them to be a waste of time. They were not dissidents or activists; they just didn’t care. This lack of interest took different forms. In his study of the late Soviet period, Everything Was Forever, Until It Was No More, the anthropologist Alexei Yurchak describes some young Soviets forming odd, apolitical artist collectives, while others joined clubs whose members passionately debated more or less everything except current events. “Everyone understood everything, so why speak about that? It was uninteresting,” a former university student told Yurchak dismissively of dissident politics. Likewise, in an exchange with an American sociologist during this period, one Soviet rock musician explained, “We’re interested in universal problems which don’t depend on this or that system, or on a particular time.” His bandmate chimed in: “People are interested in politics, and I don’t know why they are.”

These Soviet musicians might have agreed with Atwood’s suggestion that artists should focus on timeless explorations of what it means to be human. Yurchak also quotes a onetime member of an apolitical literary club remembering the group as an “artificially created microclimate”—which recalls Atwood’s vision of an artistic garden separate from politics, or the Instagrammable comfort of domestic cozy. Writing in The New York Review of Books in 2019, the British writer Viv Groskop wondered whether Westerners overwhelmed by the news might wish to adopt the Soviet tradition of “internal exile” and curl into themselves to find peace away from politics. “It is reasonable,” Groskop wrote, “to conclude that apathy must surely be defensible as some kind of political act.”

Those Soviets who withdrew from politics were responding to the boredom of a public life curtailed by official limitations on what could and couldn’t be said. Today, the boredom of the Trump era is the product of a different kind of censorship, what the journalist Peter Pomerantsev calls “censorship through noise.” Instead of the tedium of silence, this is the tedium of endless clatter. But it has the same effect. Whether you choose not to speak about politics and turn your attention elsewhere, or you decide to say the same thing over and over again, the odds are that political leadership will carry on just as it did before. So why bother at all?

The United States is not yet in the extreme circumstances in which Yurchak’s subjects found themselves. When Atwood suggested in 2017 that artists should tend their own gardens, she was not recommending that they turn away from the news entirely—after all, she’s continued to speak publicly about the Trump presidency and explore political themes in her fiction—but rather that they remember that there are ideas outside politics. If Trump retains power for a second term, though, resisting the pull of apathy may prove more difficult. This pervasive disinterest is a dangerous thing for a democracy, which depends on political engagement among its people in order to survive. And Trump would surely welcome such detachment, which would only make it easier for him to hold on to power.

If Joe Biden wins the election, this problem will likely fade when he is sworn in as president in January 2021. Part of Biden’s pitch to voters is that his administration just won’t suck up as much of their attention: As a Biden campaign ad asked in August, “Remember when you didn’t have to think about the president every single day?” But under a Biden administration, Trump will not go away, and alternative ways of engaging with him—ways that don’t cultivate apathy—will be needed for the political and historical reckoning with Trump’s legacy that will need to take place after he leaves office.

Recently, a handful of writers have begun to suggest such alternatives. “The most essential books about the Trump era are not about Trump at all,” the Washington Post nonfiction critic Carlos Lozada writes in his forthcoming book on the literature of the Trump era, What Were We Thinking. Better, Lozada suggests, to examine the forces that enabled Trump’s rise and continued hold on power. Similarly, Szalai argues in her review of Woodward’s book that “the real story about the Trump era is less about Trump and more about the people who surround and protect him.” Along these lines, Anne Applebaum recently wrote in The Atlantic on the question of why Republican leaders choose to enable Trump’s abuses, and this conversation about responsibility and complicity has continued as former administration officials and staffers seek absolution in publicly supporting Biden.

The world that made Trump possible is deeper, stranger, and more worthy of thought than Trump himself has ever been, and studying it can offer answers and insights about the current American crisis that the president, in his shallowness, can’t. This approach has another advantage too. It denies Trump the thing he wants most of all: undivided attention.