The Joy of Voting

Festival and bonfires; outrageous wagers; toasting and fasting and even fighting. Elections used to be fun. What if they were again?

In this 50th anniversary year of Selma and the Voting Rights Act, there’s been a lot of talk about the right to vote: how it was secured for black citizens in the South, and how it is being compromised anew by legislatures and a see-no-evil Supreme Court.

But for the most part, the public has ignored the talk. The whittling away of the VRA plays as a technical matter, the concern of partisan insiders. Which, increasingly, is how voting itself is seen by the large pluralities of eligible voters who sit out most presidential contests, and the outright majorities who skip other elections.

The sources of this apathy are familiar: People are too busy, the money game seems rigged, campaigns have become an ugly, unsatisfying spectator sport. The net effect is that the act of voting feels severed from personal purpose or collective identity.

But it’s possible to change that. A playbook exists. There was a time when voting meant much more than just voting. In fact, that was true for most of this nation’s history.

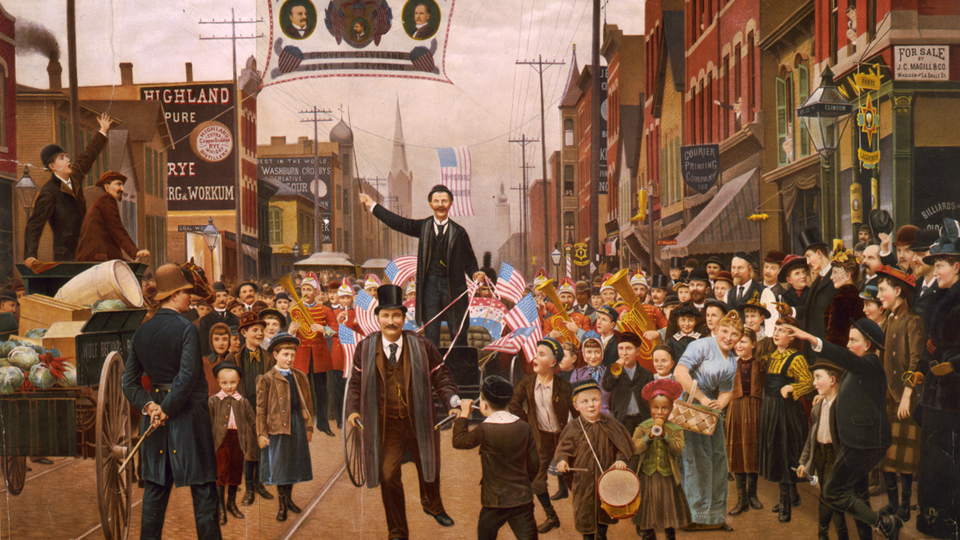

From the Revolution through the civil-rights era, as historians like Mark Brewin and David Waldstreicher describe, the United States had a robust participatory culture of voting: parades, yes, but also raucous street theater, open-air debates, broadsheets and pamphleteering, committees of correspondence, rituals of toasting and fasting and even fighting, festivals and bonfires, and outrageous wagers.

What would it look like to have a modern culture of democracy so richly festal? From time to time, we get glimpses. Think of the heady days of the 2008 Obama campaign, when Shepard Fairey and will.i.am and others made pop art out of the images and words of their candidate.

Many early Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street rallies also had a raw, homespun theatricality, from tricorner hats and Don’t Tread On Me flags to Guy Fawkes masks and “99%” iconography. And much of the post-Ferguson protest movement, as well as content created under #BlackLivesMatter, is infused with creativity.

But these are exceptions, mainly outside the electoral arena. Thanks to a half-century of TV, the couch has replaced the commons. The public sphere has become desiccated, quasi-private, and passive. The Internet makes that sphere more seemingly social. But sharing memes on Facebook and Twitter is still a quiet kind of citizenship. It’s being “alone together,” in Sherry Turkle’s phrase.

Imagine, instead, an electoral culture that’s about being together together. In person. In loud and passionate and even partisan ways. That means instead of “eat your vegetables” or “do your duty,” voting should feel more like “join the club.” Or, better yet, join the fight. The single act of casting a ballot might be surrounded with many public, participatory, and creative acts of arguing the ballot.

It would take a concerted effort—local but nationwide—to revive an array of creative, populist face-to-face electioneering rituals. Outdoor allegorical plays, in which candidates and their causes are mocked and praised in broad satirical style. Streetcorner orations by citizens making the case for their standard-bearer. Fast-paced public debates held in pubs. Battle-of-the-band concerts in which candidates are repped by competing performers. Streets with heavy foot traffic festooned with dueling handmade posters and other art.

This may sound very 18th- or 19th-century. But it only has to be as 18th-century as “Hamilton,” the new hip-hop multicultural musical about Alexander Hamilton and other Founders that’s a huge critical hit and now Broadway-bound.

Who has the time for this? Well, the average American watches five hours of TV each day. Who has the motivation? If you’re a candidate or organizer, it’ll make voters pay more attention. If you’re a voter, you get a chance to represent those who seek to represent you: to make the case for them, to argue it out with others. Everyone can be a candidate’s surrogate, not just professionals or celebrities.

What would it take to do this? Simply doing it. Yes, the screen-facing habits of contemporary democracy are deeply ingrained. But they aren’t inborn. We just need to be prompted imaginatively, conditioned by new rituals, and reinforced by the company of others. It’s the cognitive-behavioral theory of civic renewal: New habits become habit-forming.

Of course, one argument against this kind of vibrantly and visibly participatory electoral culture is that it will only magnify our already toxic levels of partisanship. But this misconstrues the problem. What we need in America today isn’t necessarily less partisanship; it’s better partisanship.

If there are deep arguments to be had on the roles of citizen and state, let’s have them. But let’s have them in less stupid, over-rehearsed, standardized, prepackaged ways. Let’s have them in engaging ways that recall the hands-on spirit of the early republic or the Lincoln-Douglas era—but that now, because it’s the 21st century, can include more than just propertied white men.

“America’s common political culture,” Waldstreicher reminds us, “consists of a series of contests for power and domination.” That will ever be true. But why let the few and the dull monopolize those contests? If elections reclaimed their pageantry, voting might recover its popularity.