The tragic stories seem endless. Sandra Bland dies in a jail cell days after a traffic stop. Philando Castile is pulled over by police and within minutes he is dead. Rayshard Brooks, who had fallen asleep at the wheel of his car and failed a field sobriety test, is fatally shot.

A new documentary, “Driving While Black,” digs deep to untangle a twisted reality. Black people continually face danger behind the wheel, and it’s rooted in history.

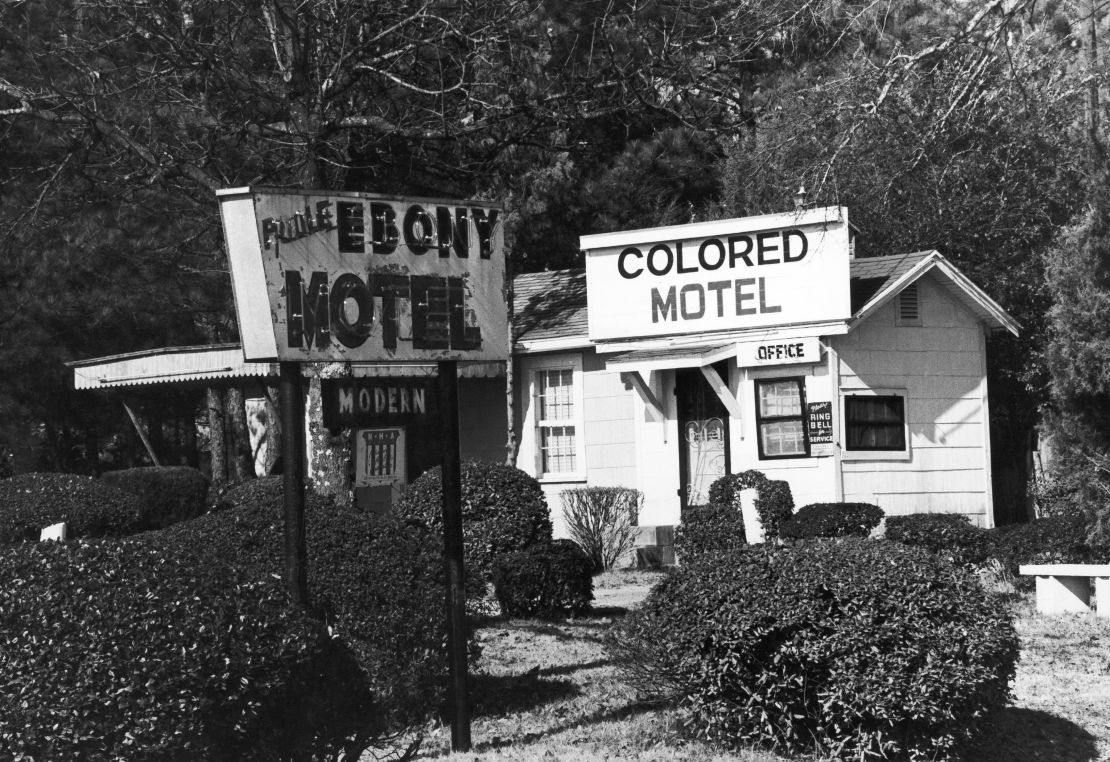

The two-hour film, premiering October 13 on PBS, winds its way from slavery to Jim Crow to the advent of the interstate highway. Through archival footage and a series of interviews, the filmmakers’ argument is poignant. When Black Americans first found their freedom to move around, White Americans pushed back fearing where they were going and why – and the remnants of that prejudice linger today.

“There are still so many dangers of being on the road,” says Allyson Hobbs, a Stanford University associate professor, in the film. “I think we’re in a time right now where African Americans are feeling a similar kind of fear as their grandparents felt in the 1930s and 40s.”

The film is about enduring racism while on the road. It threads together personal stories of harassment from famous Americans such as Frederick Douglass and Thurgood Marshall with video clips of people today getting stopped, pulled over and worse. At the same time, the film is a celebration of how African Americans embraced their freedom to travel.

Curator and historian Gretchen Sorin spent 20 years researching Black mobility and wrote the book the film is based on. After her interviews, she would ask her subjects for copies of photos and home videos. She acquired a hefty collection that helped to entice award-winning filmmaker Ric Burns, brother of Ken Burns, to work with her on a documentary.

The film documents migration patterns post-Civil War and then explodes with dazzling images of Black Americans starting to travel in style.

“The automobile is really good because it frees African Americans from the Jim Crow bus and the Jim Crow train,” Sorin told CNN. “But at the same time, there are dangers on the road.”

The not-so-open road

The filmmakers say access to cars freed Black people from the humiliation they often faced in segregated bus and train stations. When Black families drove down the new interstate highways they could bypass racist, all-White country towns. Owning a car meant Black families could move to the suburbs and be proud of the Buicks and Chevrolets in their driveways.

The emergence of the automobile, the superhighway and the road trip were remarkable developments in the US. But the film’s historians, like MIT history professor Craig Steven Wilder, want everyone to remember that progress wasn’t always kind to everyone.

“Americans in particular love to celebrate their history, but they don’t like to look at it very closely,” Wilder says in the film.

During the Jim Crow era, Black people traveled but didn’t plan on stopping much along the way. There were no gas station bathroom breaks or hunger-busting meals at local diners. Sandwiches and fried chicken were packed into coolers in the trunk. If restaurants served “colored people” at all, it was out of side windows or back doors.

The segregation plaguing the country, though, eventually paved the way for Black entrepreneurship.

A traveling network by Black and for Black

Black women soon began to rent rooms in their houses and served food to Black travelers all while providing critical information about where they could worship, get their hair done or stop over next.

In the film, Valerie Cunningham recalled how her aunt Hazel ran the Rock Rest guest house in Kittery, Maine.

“She served her guests the best of everything,” Cunningham said. “Sunday was lobster day, so that would be Lobster Thermidor. ‘Course everything was homemade.”

A network of safe spaces began to take shape, mostly east of the Mississippi, and it began to include jazz clubs and luxury hotels. Marsalis Mansion Motel in Jefferson Parish, New Orleans, and the Rossonian in Five Points, Denver, were among the many businesses owned or managed by Black people.

A number of small travel guides listed these safe spaces, but none were as successful or comprehensive as New York postal worker Victor H. Green’s “Negro Motorist Greenbook.” Green found a White publisher to print his first guides, sold copies at Black-friendly Esso gas stations and then continued printing editions from 1936 through 1967.

Sorin told CNN that Green’s mantra echoed a quote by Mark Twain that starts, “Travel is fatal to prejudice.”

She said Green believed if White Americans could see Black people traveling, they would find similarities.

“I don’t know that that’s what happened,” Sorin said. “But certainly, the encounter between some Black Americans and some White Americans did make a difference. And that’s what happens when people travel.”

Progress wasn’t equal

When segregation ended, many of the businesses that had been focused exclusively on Black customers closed. While Black people took the opportunity to patronize White-owned businesses, few White Americans did the same for Black-owned ones, according to the film.

Researchers found only 3% of the thousands of listings in Green’s book still operate today. Dooky Chase’s restaurant in New Orleans is one of those to survive and owner Leah Chase spoke to the filmmakers before she passed away in 2019.

Other listings are documented in a book by historian and photographer Candacy Taylor. Taylor drove hundreds of thousands of miles searching for “Green Book” listings in her image-packed history, “Overground Railroad: The Green Book and the Roots of Black Travel in America.”

“The ‘Green Book’ does something for us that we need,” says Wilder, the historian. “It reminds us of the world that Black people created under the regime of segregation.”

The film is a winding ride filled with highs and lows. The great highways that allow people to crisscross the country were created by paving over Black communities in their path. The automobile has become more affordable, but it’s often the way Black people encounter the police, Sorin tells CNN.

Footage of proud Black families in their shiny new cars gives way to unnerving images of Black drivers getting harassed, beaten and worse. Sorin says that her production team felt it all needed to be included.

“It’s not unpatriotic to talk about America warts and all. I think it’s very patriotic. It’s how we get better. It’s the only way we get better.”