What Will 2021 Hold for Cities?

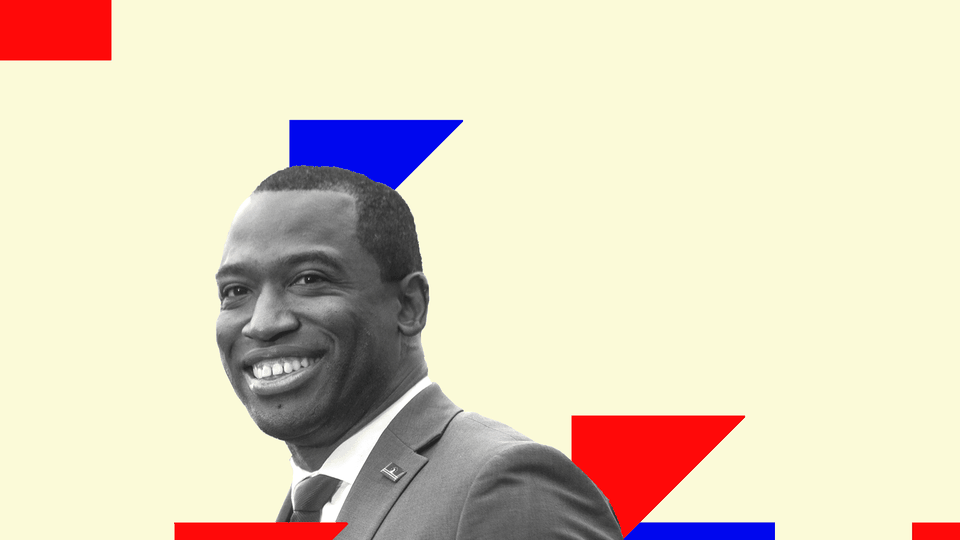

With no help coming from the federal government, can Richmond’s mayor still execute an equity agenda?

On March 6, Levar Stoney, the mayor of Richmond, Virginia, released a 2020 budget proposal full of promises. The plan featured more money for education, funds to keep people from being evicted, millions for infrastructure, and a new fund to address racial disparities in maternal health. Twelve days later, Stoney announced Richmond’s first positive cases of COVID-19. The following weeks and months created a budget crisis. Businesses closed; tax revenues dried up; support from the federal government expired.

Stoney won a second term as Richmond’s mayor last month, and he still wants to execute the ambitious equity agenda he set out in March. But how do you build a better city when the money is running out? I spoke with Stoney this week about his push to reform Richmond, this year’s racial-justice protests, and how he plans to support Black and brown communities in the absence of more stimulus money from the federal government.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Adam Harris: How were you thinking about leading Richmond through this moment at the very beginning of the pandemic?

Levar Stoney: When we first started seeing cases pop up on the East Coast, particularly 100 miles north of us in Washington, D.C., it almost felt like the walls were closing in on us. I saw the NBA had just shut everything down—that Utah Jazz game. And then the next day, we started seeing local governments do the same in our region and in parts of the South. Here in Richmond, we had a major St. Patrick’s Day weekend coming. I called the organizers of these large events and said, “I need you to cancel or postpone your event because of this virus.” A lot of them initially were like, “What?!” They spend all year planning for this. And this is where they make their money. I was able to convince just about all of them to postpone or cancel their activities. But I didn’t know that we were going to need to do more. It just started rolling from there.

I knew that the pandemic was going to have an impact on the city’s budget. Just weeks earlier, I’d given a speech I was very proud of: my budget speech for the upcoming fiscal year. And it was a bold budget, with a bold agenda attached to it, focused on equity. And I had to come back a few weeks later and cut roughly $40 million from the budget.

Harris: Was that budget an increase from the previous year?

Stoney: It was going to be an increase, because our projections looked good. We had seen some growth in our real-estate assessments. I was going to use some of that growth to fund some of my priorities in my equity agenda.

Harris: After shutting down businesses, I imagine in the background you’re thinking, This is going to have ripple effects for these businesses down the line, which has effects on the city’s budget as well. How are you talking through that with not only constituents, but also members of the city council?

Stoney: You know, restaurants have been a staple of Richmond culture for the last 20 years, I would say. We have an emerging foodie scene. And there was some initial shock to our restaurant owners and business owners. Overnight, Adam, the unemployment rate in the city of Richmond went from roughly 3 percent to 10 to 11 percent. And restaurant owners—folks who have been pioneers in the city of Richmond—took to social media truly concerned about not just their businesses, but their employees. Having to lay people off. The stories I heard of them gathering their teams and saying, “Hey, we’re gonna have to close our doors. This is our last night”—and looking at the government to respond.

I’ll admit, thinking about how tight things always are in a municipal budget, we knew that we needed the federal government to step up or we weren’t going to be able to help some of our restaurants, some of our businesses, survive this. When discussing the budget, we knew our projections were not going to be met in the upcoming fiscal year. But we also worried about the current fiscal year that we were in and whether or not we were going to find ourselves in a deficit. So I had to be fiscally prudent and freeze hiring. Freeze the discretionary spending as well; doing things I never thought I would have to do. But I also knew that we had to do this necessary work—make these decisions to protect the vulnerable communities around the city. At the end of the day, it’s those communities that were going to be on the front lines of the pandemic: bus riders, folks who are working in restaurants. I was really concerned about that. I’m going to always take advice and counsel from my advisers who work in the health world. And they told me: This is the best route for us to go.

It didn’t feel that way the first time. When you’re doing it—when you’re in it, Adam—it doesn’t feel like the right thing to do. Because folks are losing their jobs. But I always tell folks: “You can’t have a livelihood if you don’t have a life.” And looking back at it now, 80 percent of our COVID cases were from the Black and Latino community here in Richmond, which is about 54 percent of the actual population. So I made decisions—the budgetary decisions and public-health decisions—based on: What is this going to do to those communities that have been marginalized in the city?

Harris: How did the CARES Act funding help?

Stoney: Honestly, it was a godsend. We were able to stand up a couple of programs ahead of the CARES Act. We had a disaster-loan program for our small businesses. We had already launched an eviction-diversion program; we have the second-highest rate of evictions in the United States of America. I started that program, but I had to, unfortunately, cut back the expansion of it because of COVID. The CARES Act allowed us to supplement our allocation. We put roughly $14 million into rental relief and eviction diversion. And that successfully created a safety net for those who were in some of our most vulnerable communities, who were certainly at risk of falling through the cracks.

Harris: Right as people are starting to understand that COVID was going to be with us for a long time, there was the murder of George Floyd; then there was the reporting on Breonna Taylor’s killing. People took to the streets in protest. What was that moment like in Richmond?

Stoney: There really isn’t a blueprint or playbook for anything like it. To navigate an uprising, and also the pandemic at the same time, and an economic downturn as well. As mayor, I’m responsible for the health and well-being of all my residents. But Richmond, being the state capitol, presented the biggest stage for folks to express themselves in reference to the injustices that Black and brown communities have been facing for generations. And when you add on top of that, Adam, the fact that this is the former capital of the Confederacy—and we had these racist Confederate monuments that dotted the landscape—I knew that we were in for something a little different compared to what the city’s experienced in the past.

To me, there were a number of different factors that led to people taking to the streets. It was the pandemic—but also that, you know, Richmond played a singular role in the slave trade. And I don’t think we ever really healed or reconciled what occurred before 1865 or after 1865. We made some serious progress; that’s for sure. But the reckoning, I thought, presented some opportunities for meaningful reconciliation.

Harris: Activists had a lot of demands. How were you thinking about what the next steps were?

Stoney: I think sometimes what’s missing is that we had already begun working on a lot of what they had demanded. But obviously, this is no secret: The government can move a little slow at times. I thought, Well, we have to find ways to deliver that aren’t just performative. We have to be committed to the substantive change as well. But I will say, I believe the removal of those Confederate monuments—although some people will say, “Oh, it’s just symbolic”—remember where we are. This isn’t Memphis; this isn’t New Orleans. This is Richmond, Virginia: the former capital [of the] Confederacy, the second-busiest trading post for the domestic slave trade in the country. And we removed bronze and granite monuments to racism and to the Confederacy, which no one—Black or white resident—could ever foresee in their lives. And I credit the community that came out and made their voices heard.

It’s hard to have a conversation about healing and reconciliation when you drive down Monument Avenue and there’s five two-to-three-story-tall Confederate statues staring at you. That’s a hard thing to do. You want to talk about racial reconciliation? Well, what’s going on behind me here? There’s a school named for Jefferson Davis. There was a school named for J.E.B. Stuart.

I’d never visited one of those monuments before, because why would I? Why would you catch me over at Lee Circle? It is not something that I would do. But I pledged to march with some of the protesters on June 2. That evening, I walked down to the circle, and there were thousands there. That was the first time ever I’d been in the presence of that monument. And I knew after returning home that day—it had been a long, exhausting day—that we had to do something.

Harris: What were your thoughts when you stood there and were looking at the monument?

Stoney: I had always spoken about how the rationale behind those monuments—they were put up there to intimidate us. To let black folks know that “Yeah, the war is over, but we’re still in charge.”

I’d seen it from afar. I’d definitely jogged and run 5Ks and 10Ks along that stretch, but I’d never been up close and personal with it. I have to say that it is a feeling that I never felt before. Particularly being in that situation with the crowds; the mass of humanity was there. It was unlike anything I’ve ever felt in my life.

Harris: This was a signature moment heading toward your reelection. The removal of these monuments was something that people have been calling for for a long time. Now you have to think about what’s next. But you’re also in this moment, where there is likely not going to be any relief for states and cities in a COVID stimulus. What can you do now, facing a budget crisis without additional federal aid?

Stoney: The No. 1 priority has to be getting as many people as possible vaccinated. And then we can begin the real, true recovery. But I’ve got to find a way to survive as a city government between now and July 1. And that’s a serious feat.

We’re already looking at a roughly $14 million deficit at the moment. We’re gonna have to find—we are gonna have to cover that hole. I’ll admit when I hear Mitch McConnell talking about “Cities and states have to tighten their belts, and they need to get their houses in order”—it’s almost as if Mr. McConnell doesn’t recognize the people who depend on us each and every day. We are truly the front lines: local government. And the people who are depending on us are the ones who are battling the challenges of poverty in urban locales. Forty percent of my children are living under the poverty line. Twenty-one percent of my people are living under the poverty line. And the federal government is saying for us to do without—do the best we can with less. And that’s very difficult to tell a family of three, led by a single mother, that this is the extent that we can help with. Luckily, child care is included in this one. But that’s very tough—that’s a really tough responsibility to put on local governments. A punting of responsibility, frankly, from the federal government.

Harris: When you think about the equity agenda that you’ve wanted to execute, are there ways to get some of that done? While you’re also considering the fact that you may have a $14 million deficit? What are the things that can be done to make a city more equitable in the absence of additional resources?

Stoney: I think we began that work prior to the pandemic, prior to the unrest. Whether it’s our work on climate justice and building new green spaces in Black and brown communities that were long marginalized because of redlining. We created an office of equitable transit and mobility, because we know who’s depending upon our local transportation system the most—and we want to make sure as we grow the system that we are targeting those funds to the communities that need them the most. We built new schools in the city; we plan on continuing to build new schools in the city in Black and brown communities. Just this past week, a city-council panel approved my proposal to create a dedicated funding stream for affordable housing in the city, so we can create 1,000 units of affordable housing over the course of the next decade. So some of this, I would say, Adam, is focused on changing systems. And sometimes you don’t need money to do that. Sometimes you just need the will, the political courage, to actually change the way the system works for other people.

I always say this, and I think it’s important that people hear this: No, I cannot guarantee that the 230,000 Richmonders will be successful. But what I can do is remove the barriers to success. To me, that’s what justice and equity means over the course of this next decade. The way the system was created, it was created with these barriers for people who look like us.

All we are requesting the government to do right now is help. And I think that’s what our equity agenda has been focused on. How do you provide some help in these times? And also recognizing that we want to provide the best to everyone—but “the best” may mean us doing a whole lot more for a neighborhood in the East End compared with a neighborhood in the West End.

Harris: How do you convince the neighbors in the West End—who may now think that they’re being slighted because those resources are going to the neighborhood in the East End—that this equity agenda is the right thing to do?

Stoney: I think my residents in the West End understand that we are a more competitive and more attractive city when we have better schools and high-quality housing. When we can create generational wealth for many people, not just for a few. That’s the way. But also, honestly, it’s morally the right thing to do.

I think folks recognize now that this decade is so significant, and we have to get it right. It will mean people are going to be uncomfortable. But I do believe there’s gonna be some good that comes out of what occurred in 2020—and where we could be, come 2030.