Dot-Com Survivors Have Wisdom for the GameStop Crowd

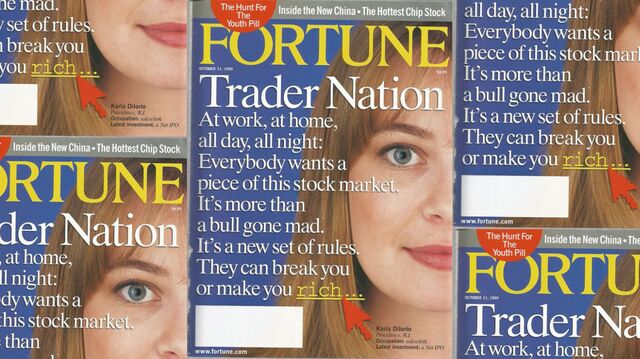

In October 1999, five months before the internet bubble burst, I wrote a cover story for Fortune magazine titled “Trader Nation.” It was about how middle-class Americans were embracing the stock market, with some even quitting their jobs to become day traders. I’ve mentioned this article before, but given the Reddit/meme stock craziness about companies such as GameStop Corp. and AMC Entertainment Holdings Inc., I thought it would be worth talking to some of the people I interviewed then to glean some lessons about how living through a stock bubble can affect investors for the rest of their lives.

I set the article in my hometown of Providence, Rhode Island, a city, as I wrote, that had always been “suspicious of the activities that generated wealth in America.” I could scarcely have imagined Providence residents getting caught up in the stock market.

But they had. One of my brothers, who worked for the city’s twice-convicted¹ but thoroughly charming mayor, Vincent “Buddy” Cianci, told me that Cianci was addicted to the market. My brother got me in to see him.

“I got a hot tip on a medical stock,” Cianci confessed. “How much did I lose on that?” he asked his assistant, Dottie. “About $3,000?”

“Something like that,” Dottie replied. He chuckled and then went on to explain, among other things, that he checked his portfolio daily, that he preferred mutual funds to individual stocks and that he had invested $50,000 in a hedge fund run by his nephew — an investment that, to his delight, had turned into $240,000.

Alas, Cianci died five years ago, so I wasn’t able to ask him whether he remained captivated by the market once he went to prison for racketeering in 2002. I’m guessing not. The dot-com bubble, after all, had burst by then. Cisco Systems Inc., the best-performing stock on the Nasdaq in the 1990s, went from $74 a share in April 2000 to $19 by May 2001. The disastrous AOL-Time Warner merger was proving, well, disastrous. Dozens of dot-com darlings — eToys.com, Webvan, Pets.com and Eve.com among them — went out of business.

One Rhode Islander I interviewed who was scarred by his dot-com experience was Michael Moffitt. Moffitt was 23 when I met him, working for Suretrade, an early do-it-yourself electronic trading platform owned by FleetBoston Financial.² Suretrade had around 350,000 customers, and many, if not most, were day traders — indeed, according to its founder, Don Montanaro, Suretrade was rated the No. 1 platform for “aggressive investors.”

Montanaro liked to call Moffitt “lobsterboy” because he had joined the company after working on a lobster boat — which is where he got his first taste of investing. The owner of the boat, Richard Cook, had told him that he should start putting money in the market while he was still young. But more than that advice, Moffitt could see that even the fishermen were trading tech stocks. (“You’d be surprised how many guys you see in lobster boats reading the stock pages in newspapers,” Cook told me in 1999. He abandoned the market long ago and now runs a fish store.)

At Suretrade, Moffitt got caught up in the excitement of watching the market surge upward. When he heard about an e-commerce penny stock, called Econnect Holdings, Moffitt plunged most of his savings into it, at 50 cents a share. Within a few months it was a $20 stock.

Yet instead of feeling joy, Moffitt felt anxiety. “I was so stressed out,” he told me. “I was losing sleep.” Other shareholders urged him to hang in because it was sure to go higher. But he was too panicked. So he sold the stock — and it turned out to be the luckiest trade of his life. Within days, trading was halted. When it reopened, it was a $2 stock.

“It turned out to be a typical pump-and-dump scheme,” Moffitt said. “I was young and stupid and lucky.” Although the money he made in the stock was enough to pay for his wedding and a down payment on a house, he never took that kind of risk again. He also quit Suretrade and started a painting business with his father, which he now runs with his wife. “We make real money,” he said, “that doesn’t go away.”

On the other hand, Moffitt’s former boss, Montanaro, never stopped being a believer. “Some of those stocks back then were stupid,” he acknowledged, “but if you bought 100 shares of Amazon³ back then, they’d be worth $400,000 today. Not every company was a stinker.”

In late 2004, after leaving Suretrade, Montanaro started a second electronic-trading company, TradeKing. Its innovation was to use social media to allow investors to talk to one another on a trading platform. “It was mainly used for education,” he said. “It was a way for savvier investors to help out their brethren.” It grew rapidly until the financial crisis hit and is now a part of Ally Financial. Montanaro is now a venture capitalist who invests in early-stage fintech companies. He has spent his career helping to make the market more accessible to individual investors.

When I asked Montanaro about his own investing behavior, he surprised me. “I learned during the dot-com era that I was not a great stock picker. So I have focused on broad-based ETFs and index funds,” he said. When I suggested that perhaps he was the equivalent of the guy who got rich during the gold rush by selling shovels to miners, he took umbrage. “Most of the miners never found any gold,” he replied. “With investing, there really is gold in those hills.”

•••

Ramesh Gulati was a 29-year-old financial adviser who had just gone out on his own when I met him in 1999. “When I go to a kid’s soccer game,” he told me when I asked him about the dot-com frenzy at the time, “people will start asking me about various stocks.” Now, at 51, he’s still a financial adviser — and from where he’s sitting, it’s deja vu all over again.⁴ “My nephew and my son keep talking to me about GameStop and AMC,” he told me when we spoke recently. “I tell them it’s just crazy. Complete and absolute gambling.”

During the dot-com bubble, Gulati did a fair amount of gambling himself — “I remember trading stocks like CMGI and Priceline,” he said. “I was day trading for my family and for certain clients who wanted that.” When the bubble burst, he recalled, “people were shell-shocked. A lot of people either sold their stocks or went into hibernation.” Eventually, many of them decided they were better served with a broker or an adviser than a do-it-yourself electronic platform.

Gulati didn’t get out of the market entirely, but he became skeptical, even gun-shy, for the better part of the next decade. “Don’t forget, a lot of bad things happened after the dot-com bubble,” he said. “There was Enron, and WorldCom, and Bernie Madoff, and the bank bailout during the financial crisis.” During the bubble, he was fully invested and had margin accounts. Afterward, he usually held an excess of cash in his portfolio, just in case.

“I’m still using hedging and options, and I get on momentum stocks once in a while,” he said. But the memory of the dot-com crash never completely goes away. When a shopkeeper friend recently stopped him on the street one day to ask him about SPACs, Gulati’s first thought was: “It’s happening again.”

•••

The person I assumed would be the most scarred by the dot-com bubble turned out to be the one who was the least affected, at least psychologically. I can still picture Ron DiIorio in a back room of a small jewelry store owned by his family where he and his wife, Karla, ran a small graphics company. He was hunched over a computer, poring over stock information. He told me he had accounts with three online brokers and links to a dozen different chat boards. His favorite was Silicon Investor.

He also told me that he had had been able to acquire some pre-IPO shares for a local internet company called Log On America. Dot-com stocks were making huge first-day jumps when they went public, so DiIorio sank everything he could into those shares. But he was restricted from selling them, so he could only watch helplessly as the stock fell from its IPO price of $37 to $19 by the time I visited him in October. I had a sinking feeling even then that this wasn’t going to end well.

It didn’t. By 2002, Log On America was bankrupt, and when I caught up with DiIorio recently, he told me that by the time he could finally sell the stock, it was basically worthless. He chuckled. “That was one of the first lessons I learned,” he said. “If they’re going to lock it up, you better own the company.” He continued: “That was a big loss for us. We were young and starting out. But when you are that young, you can take the risk.”

Unlike many of the others I spoke to, DiIorio never lost his taste for risk, even as he opened a chain of hearing-aid stores. “I like stocks that are trading 20 to 40 times earnings,” he said. Tesla was his kind of stock. He did well enough in the market that when he sold his company a half-dozen years ago, he and his wife were able to live comfortably on their investments. Most recently, he had moved most of his portfolio into cryptocurrency and blockchain companies. “This is the next revolution of the internet and finance,” he said.

DiIorio notwithstanding, what I mainly discovered in talking to the people I’d interviewed 22 years ago was that the most successful investors were the ones who learned that day trading is not the path to wealth. Investing for the long term is. Rebecca Whitaker is a compensation expert who was 23 when I met her on the Suretrade trading floor, where she was a junior employee. She had taken finance courses at Providence College, where she was taught that “If you invest, you’ll be able to have a long retirement.”

But, she added, “they never told you about the big swings I was seeing every day. You’d see people gain or lose huge sums of money between the time the market opened and the time it closed.” At first, she wanted to join in, but she didn’t have any money to invest. She now views this as a blessing.

Stacy Paterno, meanwhile, was a public relations consultant I met during a meeting of an investment club I attended. They called themselves the Enterprise Club, and this was their first meeting. Five of the 11 women in the room gave long — and impressive — presentations about stocks they had been assigned to research. None were dot-com stocks. It became clear quickly that these women were from the Warren Buffett school of investing: find value in well-known names, research the heck out of them and hold them for the long haul.

I remember thinking that this club was not likely to last long because the amount of work they were assigning themselves would put most mutual fund managers to shame. When I spoke to Paterno the other day, she confirmed that the club had soon faded away. But she added that its ethos — slow and steady wins the race — never left her. She told me that her long-term investments in mutual funds and a few blue chips had largely put her four children through college and that she and her husband had been contributing to an IRA since before they were married. Retirement, apparently, wasn’t going to be a problem.

When I asked her why she hadn’t gotten caught up in the dot-com craziness, she replied, “I just think we’re not risk-takers.”

Whitaker wound up not being a risk-taker either, scared off by her experience at Suretrade. When I asked her what she thought about the meme stocks, she replied, “I feel like I’m back in the internet bubble.”

“People I know who day traded always lost money in the end,” she said. “I would hear day traders on the phone every day frantically trying to make a trade before it was too late.” In her view, the GameStop phenomenon was about “the younger generation learning about day trading” — just like her generation had to learn.

I know there’s a theory that it’s somehow different this time, maybe because the motivation of the Reddit traders is different, or because they are shrewder about the stocks they are picking, looking for small floats combined with large short interest. And sure, that’ll work for a while.

But people who’ve been around the block a few times — people like those I met in Providence 22 years ago — know that this won’t end well for most of the Reddit traders. They’ll lose money, and the experience will affect them for the rest of their lives. With investing, there is no lesson so powerful as losing money. Sooner or later, the GameStop day traders are going to learn that lesson — just as their forebears did during the dot-com bubble.

(Corrects the surname of Don Montanaro, the founder of Suretrade, in the seventh paragraph and later references.)