How to Turn an Oil Boom Town Into an Oasis of Renewable Energy

After pumping oil for more than 70 years, the birthplace of China’s petroleum industry is going green.

In a town on the edge of the Gobi desert is a sign in English and Chinese that reads “Oil Holy Land.” Nearby, a preserved drilling rig marks the spot of China’s first commercial oil well.

All around, coated in snow on an April morning, are streets of abandoned buildings, their rooms littered with trash, torn wallpaper and broken furniture and smashed window panes.

This is Yumen, “the cradle of China’s oil industry,” that has become a totem for China’s changes over the past four decades—from a time of sacrifice and ideology to one of entrepreneurs and the pursuit of wealth, from the old economy to the new, from fossil fuels to renewable energy.

As the old town dies, a new city center is rising an hour and a half’s drive to the west, on a fertile oasis by the old Silk Road. Here are wide streets, new schools and apartment blocks and optimism. Instead of oil derricks and nodding donkeys, the flat plains around New Yumen are covered with rows of wind turbines and fields of solar panels.

The contrast has made Yumen a byword for energy transformation, a town that shrugged off the mantle of oil and embraced the future. But the reality is not so simple.

Old Yumen is dying because for the past 20 years it has been running out of oil, landing it on a growing government list of “resource depleted” cities that the state is spending billions to rehabilitate in an effort to prevent social unrest.

After President Xi Jinping set 2030 as the date for China’s emissions to peak and 2060 to become carbon neutral, the effects on cities across the country are likely to grow as they grapple with tighter rules to control pollution.

“Everyone in China’s oil industry has a special feeling for Yumen,” said Yang Fuqiang, a research fellow at Peking University’s Research Institute for Energy. “The resource cities sacrificed themselves for the whole country’s development and when they decline the country should help them.”

Few fell as hard as Yumen. This is the birthplace of Wang Jinxi, the “Iron Man” oil worker and Communist Party hero who worked so hard that he sometimes forgot to eat.

Countless images and statues of him adorn the town, part of the old Party playbook of fashioning worker superheros to inspire the masses. “It’s so honorable to be an oil worker; wherever there is oil, there is my home,” sing Yumen oil workers in a famous 1960s propaganda song.

Vestiges of those glory days remain in the town. “Everything is for the oil; everything is for the motherland,” says an old sign on a shuttered government building.

In its day, Yumen fueled the fledgling communist economy, drawing thousands of oil workers, retailers, restauranteurs and all the other migrants of a boom town. It became one of the richest cities in the country and when China began to open its economy in the 1980s, a new wave of entrepreneurs arrived to try to get a slice of the wealth. In the 1990s, this remote spot in the arid hills above a desolate plain had 130,000 people and 285 karaoke bars, according to state-owned China Petroleum Daily.

“We moved here because it was much easier to make money here from the workers who got paid every month,” said 42-year-old Zhang Qingxia, who arrived with her husband from a nearby city in 1997 to run a grocery shop. “In my hometown, people had no money.”

China's First Oil Town

On the edge of the Gobi Desert, Yumen is trying to upgrade

Liu, a 25-year-old engineer at state oil company China National Petroleum Corp., grew up in the city just as the heyday was ending and remembers long queues outside the 300-seat Oil Workers’ Cinema at weekends as people waited to watch the latest Hollywood films. His favorite food is the spicy cuisine of Sichuan, a testament to the cooks who migrated from the province 1,900 kilometers (1,200 miles) away.

But the restaurants and shops depended on petroleum, along with 90% of the town’s industry and 60% of its revenue. When the oil started to run out, the decline came rapidly.

Workers and their families began to leave, many to the far western province Xinjiang where CNPC was opening up new fields. With them went the good, company-owned schools and hospitals. In 2003, the municipal government relocated back to the desert oasis where the original town had been for hundreds of years before the oil was discovered. The few remaining oil workers mostly have homes and families in nearby cities and commute to work.

“There is no life here, and there is no future,” says Wei, while having lunch in a CNPC canteen with hundreds of coworkers, wearing red company uniforms. Wei, who like most Chinese only gave his family name, was born in Yumen, but his wife, child, and parents all live in Jiuquan, 150 kilometers away. Along with 7,000 employees from Yumen Oilfield Co., a unit of CNPC, he comes to the town each Monday morning on a company bus and lives in a dormitory during the week.

In less than a decade, at least 52 companies went bust and more than 8,600 workers were laid off. The population fell to 30,000. Some remain because of nostalgia, others are too poor to move. A few, like 54-year-old Zheng, are paid by the government as caretakers of the dying town. He earns about 1,500 yuan ($234) a month to stop scavengers stealing metal or anything useful from a cluster of abandoned residential blocks. On a snow-covered April morning, the heating didn’t work and Zheng spent most of his time napping beside an electric radiator.

“It’s just a way to making a living and get the government to pay my pension later,” he said.

As one of China’s 69 “resource-depleted cities,” the government is trying to help Yumen transform. But there’s little it can do for the old oil town. No one would build a city here if it wasn’t for the black gold.

Like other decaying rust-belt towns, job losses, a collapse of housing prices and the loss of civic amenities led to anger among those who felt they had been abandoned. In some cases the emotion boiled over into street protests and violence, one of the most sensitive threats to the ruling Communist Party.

The central government allocated hundreds of billions of yuan to revive and clean them up. And to prevent more populations from suffering the same fate, China listed 262 urban areas as “resource cities,” with a plan to enrich and upgrade their industries between 2013 and 2020.

“When a city has become ‘resource depleted,’ it’s too late, like a patient reaching the terminal stage of cancer,” said Li Ang, research director at Innovative Green Development Program. “Cites should find new opportunities when they still have the resources they can use. The problem was not formed in a day so the transition also takes time.”

The local government wants to turn the old city into a “red tourism site,” a well-trodden path for once-famous towns that now have little else left to offer. But in this remote, inhospitable spot, it’s a forlorn hope. On a weekday visit, the museum dedicated to “Iron Man” Wang is empty save for two guides chatting to each other.

The proposed fix for Yumen is still based on energy, but this time on harvesting the winds that blow across northern China, periodically carrying sandstorms hundreds of kilometers to Beijing.

The change is taking Yumen back to its roots. A new city is being built on the irrigated plain to the west next to the original Silk Road settlement, where farmers have grown crops for centuries before the oil boom shifted the town to the hills.

On a recent weekday afternoon, people are talking and strolling in the new Municipal Square and public park. In the nearby Youth Center, art clubs recruit students with an interest in ballet, guitar, singing and painting. Cranes and bulldozers are busy building more apartments and facilities.

The development and optimism are a product of the giant renewable power projects in the surrounding area. On the outskirts of the city a sign announces: “Yumen Wind Power Tourism Scenery Site.”

Companies including Datang Yumen Wind Power Co. and China Longyuan Power Group Co. had installed as much as 3.1 gigawatts of renewable capacity by the end of 2020, mostly wind power, and the city government plans to add another 16GW by 2025. It hopes a surfeit of cheap, clean energy will attract power-intensive industries such as data centers and hydrogen production.

But Yumen isn’t the only city in the nation with this idea. The project in Gansu is one of six mega wind projects in the country and there are countless smaller ones. China added more wind-power capacity last year than the rest of the world combined, according to clean-energy research group BloombergNEF. And Gansu’s remote location means higher transmission costs and losses to send its power to big urban markets.

“A straightforward link between solar and wind power and a city’s economy is to build supply-chain factories,” said Jonathan Luan, a BNEF analyst based in Beijing. “The tricky thing is, many cities have the same plan to attract other industries with their green power, and Yumen doesn’t have anything special to win this competition.”

Many of the new buildings in the city have yet to find occupants. In front of the Yumen Citizens Center, a woman called Chen said the problem is there isn’t enough work. “Even though this city has been prettied up, it’s still hard to find jobs as it’s historically an agricultural area,” said Chen, who has lived here for 50 years.

In the early days, oil wells and refineries required thousands of workers, but, once they’re constructed, wind and solar farms require only a few.

To try to entice people to the city, the government has begun offering 15 years free education to residents’ kids, six years more than is normal in China. A free medical service for children is also being rolled out.

Yet Yumen does have one potential ace still up its sleeve in an effort to regain the glory days and leapfrog back to the forefront of the nation’s energy technology.

Next to the Arts Center in the new city center is a building with the curious title: The Living Room of Yumen Thermosolar Town. Its doors are locked—a government official said they are only opened for visiting dignitaries—but inside is an exhibition detailing Yumen’s big new energy gamble.

A giant project is taking shape just outside the satellite town of Huahai, and Yumen officials hope it will put Yumen back in the vanguard of the nation’s energy sector.

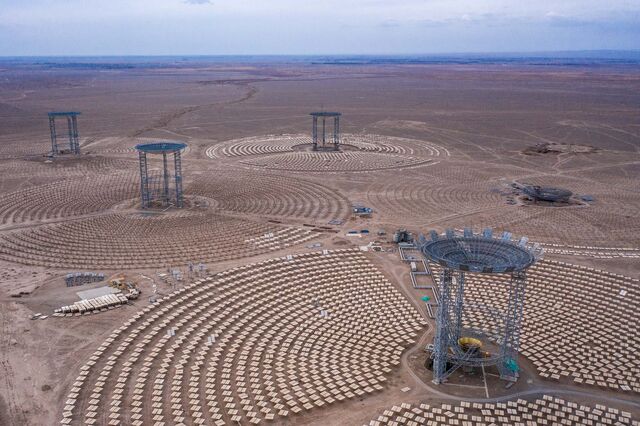

On a flat, featureless track of desert, giant rings of mirrors are being installed. In the center of each circle is a tower, designed to receive the reflected sunlight and concentrate it into a beam that will melt salt, generating enough heat to run a thermal power station.

It’s a bold bet. Concentrated solar power has been tried in one form or another in many countries, especially in Spain and the U.S. Its advantage over traditional solar panels is that it can store energy as heat, to be released at night or when demand rises. But the technology has struggled to bring down costs as fast as its ubiquitous rival, the photovoltaic panel.

Of China’s 20 demonstrator projects to test different approaches to the technology, four are in Yumen.

“Yumen has become famous for being China’s Three Gorges Dam of wind power,“ local Party Committee member Cao Jianhong told Chinese media. “In future, Yumen will aggressively promote the development of thermosolar power.”

If it succeeds, Yumen could once again be a pioneer of China’s energy industry. But the giant statue of Iron Man Wang in the new city center will always be there as a reminder of why the industry came to this remote spot in the first place. —With Allen Wan, Karoline Kan and Adam Majendie