How to Fix America

Take a road trip from New York to California to see infrastructure projects with the potential to make cities more livable and equitable.

In 2011, then-President Barack Obama stood in front of the deteriorating Brent Spence Bridge linking Ohio and Kentucky with a plea to Republican leadership: Pass the jobs bill to rebuild America. (It did not pass.) Six years later, when asked about the same bridge, then-President Donald Trump answered “we’re going to get it fixed.” (It did not get fixed.)

It took two trucks colliding on the Brent Spence’s lower deck — leading to a massive fire — just before 3 a.m. on Nov. 11, 2020, for work to begin. A post-crash inspection found the bridge structurally sound, and more than $3 million in repairs were made by year-end. But with traffic volume at around double its intended capacity, much more work is needed to alleviate persistent jams and accidents.

Such has been the state of infrastructure in the U.S. for decades — fixes get put off until they’re absolutely necessary, and U.S. airports, roads and public transportation draw frequent comparisons to those in nations with far fewer resources. Meanwhile, countries in Europe, Asia and the Middle East have leapt ahead with so-called smart cities, high-speed trains and eco-friendly buildings. In 2019, the U.S. ranked 13th in the world in a broad measure of infrastructure quality — down from fifth place in 2002, according to the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report.

But Covid-19 has pushed the much-touted idea of “infrastructure week” closer to reality. U.S. cities and states have rebounded from the pandemic faster than anticipated and are experiencing a double windfall of tax revenue and federal rescue aid. With this momentum building, Bloomberg CityLab looked across the country to identify projects that have the potential to transform the communities they serve, and beyond.

After a year of staying close to home, we picked a dozen locations to create a cross-country road trip that includes initiatives small and large, in progress and proposed, fully financed and as yet unfunded. The journey starts on the I-81 highway running through Syracuse, New York, and ends in the sinking soil of the San Joaquin Valley of California; on the route are visions for a state-of-the-art airport in Orlando, Florida, and a parking-lot-turned-playground in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

In picking locations, we considered how certain projects could help in the fight against climate change and make more equitable cities that improve livability for all residents. The list is by no means exhaustive. There are many topics — including broadband internet access, child care and subways — that aren’t tackled here but will be in future articles.

Bridges like the Brent Spence have continually been held up as the epitome of crumbling U.S. infrastructure, and the coming wave of projects will certainly be more about maintenance than fresh construction efforts on the scale of Boston’s Big Dig or the Hoover Dam. But quality of life improvements will play a bigger role, too. The ongoing semantic debate over what is and is not infrastructure doesn’t bode well for the completion of projects, many of which will require years of planning and financial follow-through. And whether the topic is the environment, education or jobs, one thing is clear: There are both immediate and long-term effects for the actions we take now — and especially for the ones we do not take.

- Syracuse, NY Reconnect a divided community

- New York, NY Make big buildings energy efficient

- Baltimore, MD Fix public school buildings

- Washington, DC Modernize America’s Union Station

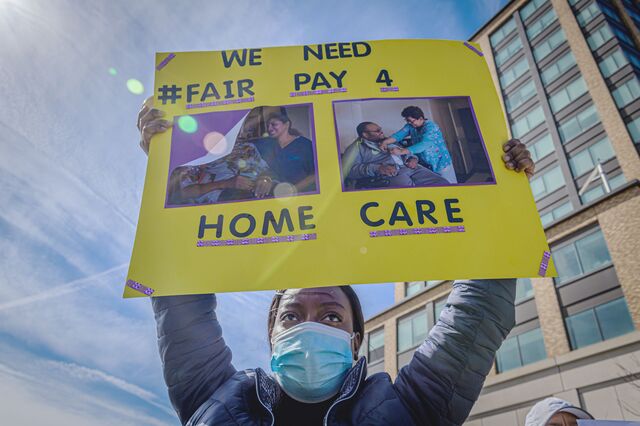

- Charlotte, NC Make home care a stable career

- Orlando, FL A more efficient Orlando International Airport

- Atlanta, GA Permanent housing for veterans in need

- Chattanooga, TN Green a redlined neighborhood

- Indianapolis, IN Expand transit access

- Austin, TX Create resilience hubs

- Denver, CO A citywide boost for electric cars

- San Joaquin Valley, CA Rebalance an overdrafted aquifer

Reconnect a divided community

Syracuse, New York

$1.9 billion

2027 at soonest

25% reduction in fine particulate air pollution, almost $140 million in new real estate value

No Highway, Less Pollution

Compared to the status quo, replacing the I-81 viaduct with a community grid would reduce CO₂ and fine particulate pollution.

Source: NY.gov

The elevated span that carries I-81 through Syracuse wasn’t unique when it was constructed in the late 1950s. Fueled by the federal funding that came with President Dwight Eisenhower’s Federal Aid Highway Act, scores of highways were built through the hearts of America’s cities — speeding commerce and suburban growth, yet devastating the communities they replaced and erecting physical barriers that would last generations. Syracuse was no exception: The I-81 viaduct displaced an estimated 1,300 residents from a predominantly African-American neighborhood, and left an eyesore and pollution for those who remained.

But a $1.9 billion proposal to tear down the viaduct would put Syracuse into a league of its own. With the structure reaching the end of its design life, New York state’s preferred plan for replacing it would restitch the surface street grid with a boulevard called Business Loop 81, and would also add bike lanes, improved pedestrian access and green spaces at revamped surrounding intersections. The state’s preliminary environmental impact statement, released in 2019, found that this approach would reduce vehicle-miles traveled and vehicle emissions. And a 2014 study by a group of planners and residents determined that the “community grid” approach could create nearly $140 million in real estate market value and $5.3 million in annual taxes by opening up developable land.

The state has budgeted $800 million for the project to break ground in 2022, with the expectation that this amount will include federal funding. There are signs of that happening, with President Joe Biden touting the project in the $2 trillion American Jobs Plan as an example of a program “that will reconnect neighborhoods cut off by historic investments.”

But not all Syracuse residents are so confident: The New York affiliate of the American Civil Liberties Union has warned that Black and brown residents living near the viaduct could still be harmed by construction and future gentrification if the state does not take steps like setting up a land trust for housing and working closely with neighbors to minimize noise and pollution. The organization’s 2020 report on the issue concludes: “Given the historical injuries sustained by those who lived in the 15th Ward, and the proximity of the current community to the anticipated construction, it is particularly vital to address their needs.” —Laura Bliss

Make big buildings energy efficient

New York, New York

$4 billion

2030/2050

5.3 million metric tons of GHG saved by 2030, the equivalent of San Francisco’s citywide emissions

Back in 2019, New York City passed what might be the most ambitious climate bill in the nation: the Climate Mobilization Act. The centerpiece is a mandate for owners of buildings that are 25,000 square feet or larger to cut their carbon emissions by 40% by 2030 (and ultimately by 80% by 2050). The law goes beyond energy benchmarking or disclosure policies — it’s designed to be a more aggressive kick in the pants to spur property owners to action and ignite the markets for products and engineering to help them meet those goals.

“This law could possibly be the largest disruption in our lifetime for the real-estate industry in New York City,” John Mandyck, chief executive officer for the Urban Green Council, said after its passage.

A year later, of course, an even bigger disruption arrived in the form of the pandemic, vacating office buildings and undermining rents across the city. Real-estate interests that already vocally opposed the law got to work to overturn it. New York Governor Andrew Cuomo’s nearly 4,000-page proposed budget for 2022 included two paragraphs under a subsection labeled Part R that would have drastically revised the mandate: Instead of making adaptations to reduce the carbon footprint of their buildings, property owners could satisfy their obligations through at least 2030 by purchasing renewable energy credits instead.

In the end, climate advocates and their allies in Albany prevailed: The state budget agreement announced in April preserves the Climate Mobilization Act as is. But to achieve the same goals will be an even bigger lift for landlords in the wake of the pandemic. Even with the reduced occupancy levels, the city is still roughly 10% short of its compliance target for greenhouse gas reductions. Meeting this mandate will come at a cost — an estimated $4 billion in all for the owners of the roughly 50,000 applicable buildings — albeit with offsetting energy savings and capital upgrades that will pay dividends down the road.

New York landlords may find relief from a number of federal proposals totaling $68 billion that will likely wind up in the American Jobs Plan. The proposal includes $18 billion in weatherization assistance for building owners as well as a new $10 billion consumer electrification rebate and job training program (modeled after the HOPE for HOMES Act). Boosters of New York’s landmark climate bill say that the city can pave the way for others to follow suit and build an industry for energy-efficient technologies and services. But they’ll have to defend the bill from political attacks along the way. —Kriston Capps

Fix public school buildings

Baltimore, Maryland

$5 billion

Ongoing

Fewer missed days of school due to building issues

On a sweltering day in September 2019, roughly 50 Baltimore City public schools sent students home early because they didn’t have air conditioning. Outdoor temperatures pushed into the 90s, and inside classrooms, temperatures approached or surpassed 85 degrees Fahrenheit.

It was only the second day of school.

But dismissing students early, opening late and canceling days entirely because of extreme temperatures is not uncommon. Between 2014 and 2019, Baltimore students missed 1.5 million hours of learning — equivalent to 221,000 full days — because of building-related problems, according to an analysis by researchers at Johns Hopkins University. More than 80% of those lost hours were due to the lack of heating or cooling. On other days, students missed out on learning because of issues like water leaks, burst pipes and electrical outages. And as the city began bringing students back for in-person learning earlier this year, officials have been scrambling to upgrade several of the facilities’ inadequate ventilation systems.

Earlier this year, Baltimore’s district updated a 2017 plan for new AC units and electrical upgrades in all facilities that lack them, at a cost of $40,000 to $50,000 per classroom. With more than 1,300 classrooms needing a cooling system, the district estimates the cost to be between $54 million and $68 million. That’s on top of an ambitious $1.1 billion initiative from 2013 to rebuild or renovate up to 28 school buildings, known as the 21st Century School Buildings Program. Seventeen schools have opened since with the help of those investments, with eight more under construction.

Still, the entire district faces a $5 billion maintenance backlog, due to decades of disinvestment, underfunding and project mismanagement. Out of 150 buildings, 95 are more than 50 years old, making them some of the oldest and most dilapidated learning facilities in Maryland.

For many of the same reasons, the infrastructure problems facing Baltimore’s aging schools are pervasive across the U.S. More than half of America’s public school districts have buildings that are in desperate need of repairs to and replacement of their HVAC and/or plumbing systems, according to a 2020 survey by the U.S. Government Accountability Office.

That leaves mostly children of color to bear the brunt of poor school conditions. Baltimore public schools serve nearly 78,000 students, 90% of whom are Black and brown, and more than half of whom are from low-income families. Not only do students and staff suffer from health problems because of poor air quality, the loss of instruction time can contribute to higher absentee and dropout rates, and overall lower student achievement. These consequences often follow students into adulthood. —Linda Poon

Modernize America’s Union Station

Washington, D.C.

$10.7 billion

2040

67,000 construction jobs, 35-minute faster train trip from D.C. to New York

Washington, D.C.’s Union Station is among the busiest rail hubs in the country, and it’s showing signs of its age. As the southern terminus for Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor and an anchor for numerous regional rail lines, its century-old track and platform configuration squeezes passenger capacity and slows average trip times. On top of that, the station serves as an intercity bus hub and D.C.’s busiest Metro station, yet its disjointed layout sends Greyhound customers to an upstairs parking garage and transit riders down a creaky escalator. There are also parts of the station that aren’t accessible to people with disabilities.

The $10.7 billion Washington Union Station Expansion Project proposes to transform all of the above. Modernized rail passenger platforms, tracks and concourses would triple capacity for trains, while facilities for intercity buses and transit, pedestrian and cycling access would be enhanced. Also slated are plans for a mixed-use development rising over the station and new public spaces aimed at weaving the 1907 Beaux Arts grand dame into the surrounding neighborhoods. On top of speeding travel times up the Northeast Corridor and improving connections for the ultra-diverse D.C. region, the plan is projected to create 67,000 construction jobs and generate new tax revenue and housing stock for the capital city.

After nearly a decade, planning for the project is nearly complete. Yet as it moves into the design phase, the project — led by the Federal Railroad Administration with Amtrak and the Union Station Redevelopment Corporation — remains unfunded. According to D.C. Congresswoman Eleanor Holmes Norton, the fact that the station is the only one in the U.S. owned by the federal government should make it a priority for federal funding — especially if it can be a model for the kind of multimodal transportation infrastructure that President Biden has touted. “Union Station is badly in need of modernization,” she said in an interview. “We want to make sure it meets the needs of the next century, not the last one.” —Laura Bliss

Make home care a more stable career

Charlotte, North Carolina

$12.7 billion to increase the Medicaid home care matching rate

Ongoing

A living wage for in-home care workers, individual attention paid to patients

When Diondre Clarke, 57, was exposed to coronavirus this year, she couldn’t take paid time off from any of her multiple jobs caring for elderly patients.

The agency and companies she contracts with as a home care worker provide no sick pay or vacation. And as her hearing aids start to expire, she can’t afford to replace them because she pays for her own health insurance, too. During the pandemic, her agency found itself so understaffed that she had to juggle 13 or 14 patients during an eight-hour shift.

“That's just not quality service to me,” she said. “I'm getting tired. But I've got to keep going because I have to pay my bills.”

Women of Color Make Less Money in Care Work

Data reflects median U.S. hourly wages in 2017

Source: PHI

Clarke lives with her sons in Charlotte, North Carolina, where the state’s minimum wage is $7.25 an hour. The national median wage for home care workers is $12.12 an hour, a figure that has remained persistently low over the past decade. According to PHI, a nonprofit that researches and advocates for the care work industry, 54% of home care workers are on public assistance and nearly half live in poverty. Across the U.S., women and people of color are paid less than white men in the field, despite the fact that they are disproportionately represented in it.

As part of the American Jobs Plan, President Biden proposed spending $400 billion to bolster home and community-based services. There is debate about how exactly those funds should be spent, since no one type of service or state necessarily needs attention more than others. The federal government currently splits the cost of home care with every state, matching state payments by 50% to 78%; adjusting Medicaid spending could be one way to inject new money into existing programs nationwide.

The American Rescue Plan increased the Medicaid matching rate for home care by 10 percentage points across all states for one year, while mandating that states keep their funding level; LeadingAge, an association of nonprofits that provide services to the aging, advocates for extending that funding bump long-term. More ambitious proposals would increase the federal match rate to 100%.

But it’s not certain that every state would opt into such a model or use those funds to compensate workers. Kezia Scales, director of policy research at PHI, suggests the federal government should set a baseline living wage for states to meet to be eligible for future increased funding. LeadingAge proposes strict requirements to ensure a certain proportion of that funding is spent on workforce development and addressing job quality concerns.

“There’s currently huge variation in how states provide, finance and deliver home and community-based services, and to whom,” Scales said. “There’s also almost completely universal underfunding.”

However such funds are distributed, supporting the people who provide home care services is key.

“We deserve to be able to leave work knowing that we're going to get a paycheck that's enough to pay our bills,” said Clarke. “I do enjoy what I do, and helping others feel better about themselves. But at the same time, who's going to help me?” —Sarah Holder

A more efficient Orlando International Airport

Orlando, Florida

$4.2 billion

2022/2023

Easier processing of 10 million to 12 million travelers

Pre-pandemic, Orlando was one of the most popular tourism destinations in the U.S., making Orlando International Airport (MCO) the country’s 10th busiest airport in 2019. Propelled by an ever increasing number of nearby theme parks — the most-visited being the Walt Disney World Resort — traffic through MCO jumped 64% between 2000 and 2019, compared with 43% for the average of the top 10 busiest U.S. airports. As passengers stacked up, so did congestion and waiting times.

That’s why MCO is forging ahead with a long-planned series of renovations and construction projects to modernize and hold millions more passengers for years to come. Construction on a brand new terminal on the southern side of the airport started in 2017, and the terminal is scheduled to open in spring 2022. It’ll host 15 additional gates, enabling a capacity of 10 million to 12 million extra travelers to be processed. The new South Terminal Complex is also planning an intermodal hub, offering ground transportation connections to services including Brightline, an intercity rail system operating between Orlando and Miami. While the South Terminal is close to 75% complete, the intermodal hub is further away from completion, and not set to open before 2023.

With the pandemic, the project took a hit: A hiring freeze slowed it down, and the overall $4.2 billion budget was trimmed as borrowing to finance construction became more costly. And, as with the rest of the aviation industry, the virus slashed the airport’s flow of passengers. Traffic in April 2020 was down to 4% of average pre-pandemic levels, according to a study by Slack, Johnston & Magenheimer, while total passenger numbers for 2020 were down to 22 million, from 51 million in 2019.

But construction is moving forward, because so is travel. Even with most international restrictions still in place, traffic has been steadily increasing at MCO as more Americans get vaccinated, are willing to fly again, and, in the case of Orlando, visit theme parks. —Marie Patino

Permanent housing for veterans in need

Atlanta, Georgia

$12 million

Ongoing

66 permanent housing units for veterans experiencing homelessness

“Housing is infrastructure” has emerged as a favorite refrain among Democrats. Housing Secretary Marcia Fudge says so often enough, as do members of the Squad and other Democrats in Congress. And California Representative Maxine Waters named the bill that will serve as the backbone for the housing elements in President Biden’s infrastructure package the “Housing is Infrastructure Act.”

It may be more than a mantra. Federal funding coming down the pike for alleviating homelessness — namely the $5 billion announced by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development in April — adds up to more money for cities and counties to address the crisis than many have seen in decades. Fudge and other leaders say that they want these funds to be used for permanent solutions, not for stopgap services.

Some municipalities simply don’t have the staffing or systems in place to absorb these funds, however. Community Solutions, a national nonprofit committed to ending homelessness, hopes to set the model for ways that cities can make the most of the money. Community Solutions recently paired up with a local nonprofit in Atlanta called Partners for HOME to purchase a 132-unit apartment building called Centra Villa, about 8 miles southwest of downtown.

The model is unique in a few ways. It’s a partnership between a national and local nonprofit to buy the building, an arrangement that Community Solutions hopes will showcase best practices over time. Current residents at Centra Villa will continue their leases; through attrition, the plan is to eventually set aside half the units for veterans experiencing homelessness.

The broader goal is to identify real estate opportunities that are close to services for residents, whether that’s apartment complexes like Centra Villa (which is near the Fort McPherson Veterans Administration Clinic) or motels and hotels — ideal candidates for this kind of conversion.

For its part, Community Solutions was recently awarded $100 million from the MacArthur Foundation, money that it hopes to put toward helping communities build permanent housing across the country. Federal authorities want to see the $5 billion put toward the housing solutions that they consider to be essential infrastructure, so they’re providing a long runway: The funds do not expire until 2030. —Kriston Capps

Green a redlined neighborhood

Chattanooga, Tennessee

Up to $200,000 for a community playground; $12,000 for tree planting

Late 2021

Added shade, cooler temperatures

Apart from having provided much needed time outdoors for the millions self-isolating throughout the pandemic, city parks and green spaces have another role that is increasingly important in light of climate change: They regulate temperature.

Parks and trees can protect city dwellers from the urban heat island effect, in which materials like concrete and asphalt trap and retain heat. The resulting hike in temperature can be heavily felt during the increasingly warm summer months of the last few years. A 2020 analysis by the Trust for Public Land found that communities with a park within a 10-minute walk are on average six degrees cooler than those without.

The disparity stems from a history of discrimination. In Chattanooga, Tennessee, just 38% of residents live within a 10-minute walk of a park, compared with an average 75% for the top 100 largest U.S. cities, according to TPL. There, as in many other places across the country, the map of formerly redlined neighborhoods — where would-be home buyers were systematically denied loans in the early 20th century, spurring decades of disinvestment — lines up almost perfectly with the map of urban heat islands, as a result of a lack of green space in those neglected areas.

“You really can’t pull that apart from systemic racism because of the nature of how the city developed,” said Michael Walton, president of the local sustainability nonprofit green|spaces.

Chattanooga has an average 5.3 degree Celsius difference in temperature between formerly redlined neighborhoods and those that were once rated as “best,” researcher Jeremy Hoffman and his team found in a 2020 analysis.

One neighborhood touched by this phenomenon is Orchard Knob, a historically redlined area. It’s adjacent to one of five hospitals in Chattanooga that are part of the Parkridge Health System. Orchard Knob “is just kind of a concrete area, and that drives heat indexes and temperature,” said Parkridge Chief Executive Officer Tom Ozburn. In 2019, Ozburn helped start a neighborhood collective to fundraise and organize improvements such as renovated homes, a mobile pantry, and green spaces on and around the hospital campus to be used by employees, patients and nearby residents.

Tree planting on Ivy Street, one of Orchard Knob’s main corridors, will be made possible later this year with $12,000 in funding from green|spaces and the city.

Another plan seeks to transform a parking lot adjacent to a local hospital into a community playground. While the site has been identified, funds are still being raised. Ozburn doesn’t expect tree and grass planting to be too expensive, but the price of the playground equipment could significantly drive up the costs of the endeavor: “It could range up to $200,000 depending on how big of a facility they build or produce,” Ozburn said. But it would be a small price to pay for cooler, healthier streets. —Marie Patino

Expand transit access

Indianapolis, Indiana

$169 million for one new BRT line

2024

70% more bus service when full network is in place

As one of America’s most sprawling cities, Indianapolis is also one of its least transit-friendly. Of the roughly 1 million jobs in the area in 2019, fewer than 10,000 were accessible within 30 minutes or less by bus, according to a University of Minnesota report that ranked it 36th in transit accessibility among the nation’s 50 largest cities.

Those barriers affect the city’s many impoverished households the most: Just 16% live within walking distance to a transit stop with frequent arrivals.

But a historic vote in 2016 has begun to fill in those gaps, after residents overwhelmingly passed a 0.25% income tax increase set to generate $56 million a year for modernizing the city’s transit system, IndyGo. The plan: to increase bus service by 70% with three new all-electric bus rapid transit lines, plus an overhaul of the existing bus network with an eye toward efficiency and frequency, as well as upgrades to surrounding sidewalks and pavement. The first BRT line opened in 2019 to fanfare, but then came the pandemic, which brought flattened ridership, reduced tax revenue, project delays, increased construction costs and multiple attempts by Republican state lawmakers to kill the expansion.

A Bus Boom for Indianapolis

Coming bus rapid transit lines promise expanded access

Source: IndyGo

So while the next segment, the Purple Line, is already budgeted for through tax revenues and federal grant dollars, Covid-19 is still bringing an element of unpredictability to executing the original vision, said IndyGo President and Chief Executive Officer Inez Evans.

For example, she said, the cost estimates for a new bus garage — which isn’t included in the voter-backed plan but is required to house an expanded bus fleet — has nearly doubled in the last six months due to the skyrocketing price of steel, raising uncertainty about the total cost of the BRT plan. Plus, the agency hopes to add on other features, like shovel-ready “Super Stops” that accommodate multiple buses at busy pickup spots downtown, plus park-and-ride hubs that increase access to BRT stops. And it wants to provide “right-sized” bus service in parts of the city that are especially spread-out by offering smaller vehicles on flexible routes.

The agency may seek additional federal support to bolster its transit plan as things shift. “If there are no sidewalks or density, we want to be cognizant of all of those needs,” said Evans. “If we wait for sidewalks to go into all of our service areas, it’s going to take a while.” —Laura Bliss

Create resilience hubs

Austin, Texas

$1 million for the first year

6 sites in one year

Lives saved, power gaps filled

Even before a winter storm plunged around 4.5 million Texas homes and businesses into darkness in February — leaving dozens frostbitten and more than 100 dead — officials in Austin had been discussing the creation of a web of community hubs, designed to better coordinate the city’s emergency response. But the tempest and the massive grid failure that followed highlighted the growing need to ramp up Austin’s resiliency in the face of disasters, both climate-related and human-made, and to bring both physical infrastructure and community support closer to the people who are most in need.

Now, the city council is advancing a resolution to create a pilot program of six “resilience hubs”: schools or churches equipped with essentials like power, WiFi, water, walkie-talkies, community services and support staff on call. Icy road conditions meant that in February, “people were without power — in some cases without power and without water — and with no ability to drive to another part of town where they could access those basic services,” said council member Kathie Tovo, who is sponsoring the resolution.

The goal is to eventually create a network of hubs scattered around the city, strategically placed within a 15-minute walking distance of each neighborhood or major road, so that no Austinite has to risk traveling washed-out highways to get to warmth or shelter.

The state has already prioritized weatherizing state energy infrastructure, and holding accountable the utility companies responsible for the poorly communicated forced shutoff. But targeted investment in the people and places nearest to at-risk communities will go a long way in helping the city weather the next storm, whatever it looks like.

“People have always come together in times of crisis, and crises are more frequent and more intense now. What does it look like, as we adapt? What resources do people need?” said Carmen Llanes Pulido, a city planning commissioner and executive director of Go! Austin / ¡Vamos! Austin, which advocates for Hispanic communities in southeast Austin. “And yes, it's going to be expensive. But you know what, it's a lot more expensive when we're not prepared.” —Sarah Holder

A citywide boost for electric cars

Denver, Colorado

In the tens of millions

2050

2.4 million metric tons of GHG saved if EV share hits 100% by 2050

Denver is but a short drive to some of the country’s epic mountain views, but the trek can be a smoggy one. Its inversion-prone location at the foot of the Rocky Mountains makes it among the worst U.S. cities for air pollution. So with increasing urgency to respond to climate change and a growing haze over the mile-high city, Denver’s latest action plan to tackle greenhouse gases leans on boosting adoption of zero-emission vehicles. Already, the city has one of the country’s highest shares of EVs on the road, but that isn’t saying much — it’s only 1%. By 2030, the goal is to reach a 30% EV share, and by 2050, it wants it to be 100%.

How to make that giant leap? The state provides subsidies for vehicle purchases, and there’s already a $110 million plan to boost EV chargers across Colorado over the next two years by Xcel Energy, a major utility holding company. For now, the city sees its role as encouraging more of that infrastructure. That includes moving from 700 charging ports that are currently publicly available to an estimated 4,000 citywide, something Denver plans to accomplish by requiring new homes to include wiring for EV chargers and new parking lots to dedicate EV-ready spots. This year, the city is investing $500,000 to build 27 stations for city-owned vehicles at multiple sites — on top of the 56 stations it’s already built for public use at libraries, parks and recreation centers.

“Consumers need to see that there are charging stations available with as much convenience as gas stations,” said Grace Rink, executive director of the city’s office of climate action, sustainability and resiliency. “Providing the infrastructure and encouraging it in private developers is absolutely within the scope of what cities provide.”

The plan to boost EV uptake includes residents who don’t own personal vehicles. Later this year, the city plans to connect the lower-income neighborhood of Montbello to a nearby rail transit stop with an electric commuter shuttle; last year, it used federal CARES Act money to put electric car-share vehicles in six under-resourced communities, and offer subsidies to users who need them. If federal funds were available, Rink says the city would expand such programs across Denver. —Laura Bliss

Replenish overdrafted aquifers

SAN JOAQUIN VALLEY, CALIFORNIA

$500 million +

Early 2040s

Tens of thousands of acres of new wildlife habitat, open and recreation space, and solar panel installations

To grow the almonds, citrus, cotton and myriad other crops that make the San Joaquin Valley one of the most productive regions in the world, farmers have long relied on groundwater. But decades of excessive pumping — including during droughts, when aquifers went without replenishment — have literally caused the valley to sink, threatening future supplies and infrastructure. Like a bank account in overdraft, groundwater supplies are overdue for a top-up. And with climate change further squeezing resources, some land will have to be taken out of production.

As part of his $100 billion “California Comeback” plan, Governor Gavin Newsom proposed a direct response to these complex issues: $500 million for “multi-benefit land repurposing” that provides “flexible, long-term support to water users.” Ann Hayden, senior director of the water program at the Environmental Defense Fund, said that would mean incentivizing farmers to transition their land to uses that allow for more groundwater recharge and provide other benefits like wildlife habitat, recreation space, or room for solar installations.

California’s Agricultural Heartland Is Sinking

Decades of excessive groundwater pumping has caused land to subside

Source: USGS

The investment could be a major opportunity to make room for the kit foxes, hawks, lizards and pollinators that call the area home. More than 95% of the valley’s riparian woodland areas have been lost over the last century, according to the Department of Fish and Wildlife.

“This is not just buying out land and letting it idle. That’s the last thing we’d want,” said Hayden, adding that a patchwork of dusty, vacant fields would worsen the region’s notoriously bad air. “We want to see strategic investments in a way that’s building opportunities for habitat, groundwater recharge, and disadvantaged communities.”

To balance groundwater supply and demand, as much as 750,000 acres of farmland will have to be converted, according to the Public Policy Institute of California. That area is roughly the size of Yosemite National Park. “We need more demonstrations on the ground to get farmers oriented to the opportunity and try out some of these new approaches,” Hayden said. “While $500 million is a start, it’s safe to say we’ll need a lot more to address this issue at scale.” —Laura Bliss

Graphics by Jeremy CF Lin

Updated to clarify that $4.2 billion is the cost for all renovations to Orlando International Airport