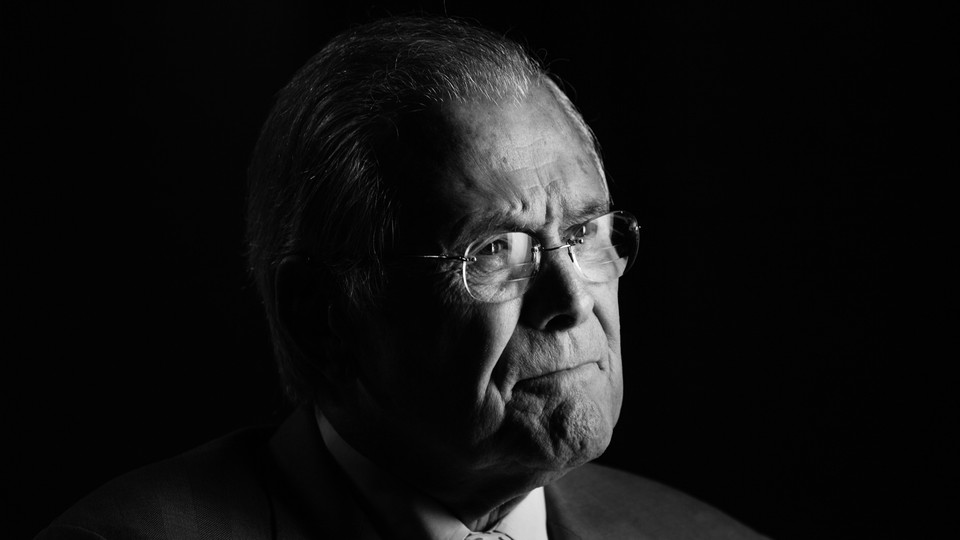

How Rumsfeld Deserves to Be Remembered

America’s worst secretary of defense never expressed a quiver of regret.

In 2006, soon after I returned from my fifth reporting trip to Iraq for The New Yorker, a pair of top aides in the George W. Bush White House invited me to lunch to discuss the war. This was a first; until then, no one close to the president would talk to me, probably because my writing had not been friendly and the administration listened only to what it wanted to hear. But by 2006, even the Bush White House was beginning to grasp that Iraq was closer to all-out civil war than to anything that could be called “freedom.”

The two aides wanted to know what had gone wrong. They were particularly interested in my view of the secretary of defense, Donald Rumsfeld, and his role in the debacle. As I gave an assessment, their faces actually seemed to sag toward their salads, and I wondered whether the White House was so isolated from Iraqi reality that top aides never heard such things directly. Lunch ended with no explanation for why they’d invited me. But a few months later, when the Bush administration announced Rumsfeld’s retirement, I suspected that the aides had been gathering a case against him. They had been trying to push him out before it was too late.

Rumsfeld was the worst secretary of defense in American history. Being newly dead shouldn’t spare him this distinction. He was worse than the closest contender, Robert McNamara, and that is not a competition to judge lightly. McNamara’s folly was that of a whole generation of Cold Warriors who believed that Indochina was a vital front in the struggle against communism. His growing realization that the Vietnam War was an unwinnable waste made him more insightful than some of his peers; his decision to keep this realization from the American public made him an unforgivable coward. But Rumsfeld was the chief advocate of every disaster in the years after September 11. Wherever the United States government contemplated a wrong turn, Rumsfeld was there first with his hard smile—squinting, mocking the cautious, shoving his country deeper into a hole. His fatal judgment was equaled only by his absolute self-assurance. He lacked the courage to doubt himself. He lacked the wisdom to change his mind.

Rumsfeld was working in his office on the morning that a hijacked jet flew into the Pentagon. During the first minutes of terror, he displayed bravery and leadership. But within a few hours, he was already entertaining catastrophic ideas, according to notes taken by an aide: “best info fast. Judge whether good enough [to] hit S.H. [Saddam Hussein] @ same time. Not only UBL [Osama bin Laden].” And later: “Go massive. Sweep it all up. Things related and not.” These fragments convey the whole of Rumsfeld: his decisiveness, his aggression, his faith in hard power, his contempt for procedure. In the end, it didn’t matter what the intelligence said. September 11 was a test of American will and a chance to show it.

Rumsfeld started being wrong within hours of the attacks and never stopped. He argued that the attacks proved the need for the missile-defense shield that he’d long advocated. He thought that the American war in Afghanistan meant the end of the Taliban. He thought that the new Afghan government didn’t need the U.S. to stick around for security and support. He thought that the United States should stiff the United Nations, brush off allies, and go it alone. He insisted that al-Qaeda couldn’t operate without a strongman like Saddam. He thought that all the intelligence on Iraqi weapons of mass destruction was wrong, except the dire reports that he’d ordered up himself. He reserved his greatest confidence for intelligence obtained through torture. He thought that the State Department and the CIA were full of timorous, ignorant bureaucrats. He thought that America could win wars with computerized weaponry and awesome displays of force.

He believed in regime change but not in nation building, and he thought that a few tens of thousands of troops would be enough to win in Iraq. He thought that the quick overthrow of Saddam’s regime meant mission accomplished. He responded to the looting of Baghdad by saying “Freedom’s untidy,” as if the chaos was just a giddy display of democracy—as if it would not devastate Iraq and become America’s problem, too. He believed that Iraq should be led by a corrupt London banker with a history of deceiving the U.S. government. He faxed pages from a biography of Che Guevara to a U.S. Army officer in the region to prove that the growing Iraqi resistance did not meet the definition of an insurgency. He dismissed the insurgents as “dead-enders” and humiliated a top general who dared to call them by their true name. He insisted on keeping the number of U.S. troops in Iraq so low that much of the country soon fell to the insurgency. He focused his best effort on winning bureaucratic wars in Washington.

By the time Rumsfeld was fired, in November 2006, the U.S., instead of securing peace in one country, was losing wars in two, largely because of actions and decisions taken by Rumsfeld himself. As soon as he was gone, the disaster in Iraq began to turn around, at least briefly, with a surge of 30,000 troops, a policy change that Rumsfeld had adamantly opposed. But it was too late. Perhaps it was too late by the early afternoon of September 11.

Rumsfeld had intelligence, wit, dash, and endless faith in himself. Unlike McNamara, he never expressed a quiver of regret. He must have died in the secure knowledge that he had been right all along.