Turkmenistan’s Dirty Secret

The former Soviet republic is one of the world’s worst emitters of planet-warming methane. Its exported natural gas is becoming crucial to China.

Carrie Herzog was sitting at her desk in Montreal one day in early 2019, studying satellite images for signs of mud volcanoes. These geological oddities, common around the Caspian Sea, can belch greenhouse gases. Herzog’s job as a technician at GHGSat Inc., a Canadian company that monitors emissions, is to identify individual pieces of the planet-warming puzzle. Her eye caught something strange on the edge of an arid, wind-scoured stretch of desert in Turkmenistan. Something that shouldn’t have been there.

Stretching north from a clutch of industrial structures in the former Soviet republic were two jagged slashes more than three kilometers long, captured by the satellite’s imaging spectrometer, an instrument that allows scientists to identify gases based on how they reflect light. Surprised, Herzog summoned a colleague. Then their superiors directed the satellite to take a closer look on its next pass. Emissions-spotters at SRON, a space-science institute in the Netherlands, agreed to examine data from one of their orbital monitoring systems. The additional measurements left the GHGSat team in no doubt. They had picked up one of the largest releases of methane ever observed in real time.

It appeared to be coming, in part, from Turkmenistan’s Korpezhe natural gas field, specifically from a compressor station, where gas is prepared for piping to customers. A researcher would later conclude that the leak had been active for more than five years. Since methane has more than 80 times the warming power of carbon dioxide when it first enters the atmosphere, this one leak had a climate impact roughly equivalent to the annual emissions of all the cars in Arizona. “We were really shocked,” says Stephane Germain, GHGSat’s founder and president. “We had something that was real and extremely significant.”

The plumes provided evidence of what climate scientists have long suspected: The world has a serious problem with methane emissions from Turkmenistan. Colorless and odorless, methane is the largest component of natural gas and can leak in huge volumes from energy facilities whose managers don’t bother to stop it. That’s something they don’t appear to be doing in the vast, sparsely populated country. Of the 50 most severe methane releases at onshore oil and gas operations analyzed since 2019 by monitoring firm Kayrros SAS, Turkmenistan accounted for 31 of them. In 2020, the International Energy Agency estimates, its overall methane emissions from oil and gas were behind only Russia and the U.S., both of which have significantly larger energy industries and populations that far exceed Turkmenistan’s 6 million citizens.

Yet unlike those nations, it’s not at all clear how Turkmenistan can be persuaded to reduce its climate impacts. Led by Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov, a dentist-turned-dictator who was reelected as president in 2017 with a purported 98% of the vote, Turkmenistan is one of the most repressive places on the planet. As late as May of this year, Berdymukhamedov insisted the country had “yet to discover a case” of Covid-19. It remains so isolated that some academics who study the country have never been granted visas to visit. The state-owned energy sector is opaque to outsiders, limiting participation by international companies to a bare minimum and providing almost no data on its operations.

What little information is available suggests that reducing methane and other emissions is hardly a priority. Two people familiar with the secretive industry, who asked not to be identified, described decrepit, poorly maintained infrastructure, some of it little updated since the Soviet era, with essential work put off for years because of shortages of funds and trained personnel. Environmental standards are routinely disregarded, according to one of the people, with no meaningful emissions monitoring and no incentive for officials to try to clean up their facilities. “Everyone just closes their eyes to the problems,” the person said. “Who will care about invisible emissions?”

For this story, Bloomberg Green sought comment from officials in Turkmenistan’s energy and foreign ministries, as well as the state gas company, Turkmengaz. None replied.

Turkmenistan’s totalitarian political system, and the intensity of the personality cult that Berdymukhamedov has constructed to consolidate his rule, invite comparisons to another hermit kingdom. “You should really look at it as North Korea without the bomb,” says Luca Anceschi, a professor at the University of Glasgow who researches Central Asian regimes. But the analogy goes only so far. Since the 1950s, a combination of military threats and economic pressure has kept three generations of the Kim family from acting on their country’s bellicose rhetoric. Turkmenistan’s threat to the outside world is more subtle. And it may be impossible to contain, at least not before much of the damage to the climate has been done.

Since the decline of the Silk Road, the fabled route linking China and Europe via the bazaars and caravansaries of Central Asia, what’s now Turkmenistan has been a long way from the main flows of global trade. When imperial Russian troops began a bloody, ultimately successful campaign of conquest in the 19th century, they encountered a landscape of fiercely independent nomadic tribes, for whom raids on passing travelers were an important economic activity. Their members weren’t citizens of any coherent polity; from the perspective of the modern international system, they inhabited a no-man’s land.

But what it lacked in geographic advantage, it made up for in geology. With an estimated 13.6 trillion cubic meters of natural gas lying below its surface—the fourth-largest reserves in the world—the region would become an important industrial asset for the Soviet Union, which took control after 1917. Russian engineers, along with Turkmens trained in the scientific academies of Moscow and Leningrad, built a substantial energy infrastructure.

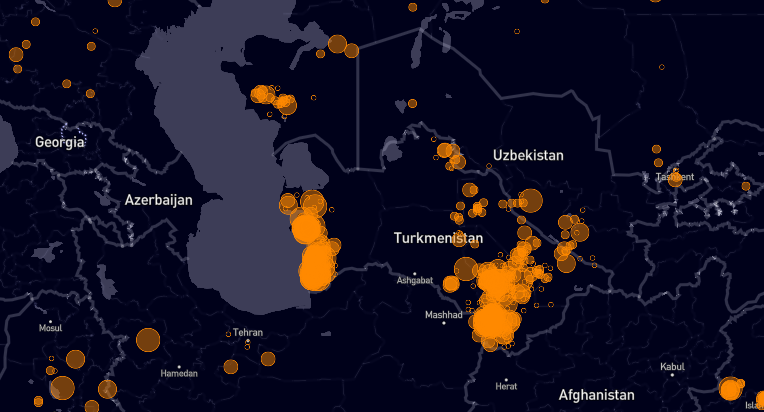

Turkmethistan

The Central Asian nation is rich in natural gas—and methane emissions

Like natural-resource projects elsewhere in the Soviet world, their work left a legacy of environmental damage. Kayrros estimates that Turkmenistan’s western region emitted roughly the same amount of methane last year as the gas-rich Permian and Anadarko basins in the U.S. combined, even though the area produces much less energy. The country’s most unique human-made landmark is the result of a 1970s-era drilling accident, when engineers shattered the roof of a huge underground gas deposit, opening a crater 70 meters wide. What happened next has never been precisely confirmed. But according to the generally accepted story, rather than let the fumes leak uncontrollably, someone decided to light the gas on fire, presumably on the theory that it would quickly burn off. It didn’t. Nicknamed the Gates of Hell, the crater has burned continuously ever since. Turkmenistan receives almost no tourists, but for the few who do visit, it’s a prime attraction.

After the collapse of the USSR, Turkmenistan was thrust into independence under the leadership of a senior Communist Party apparatchik, Saparmurat Niyazov. He bankrolled himself with gas sales, renamed the months of January and April for himself and his mother, respectively, and established a national holiday to celebrate the virtues of the Turkmen melon crop. Niyazov also relentlessly hounded journalists, activists, and anyone else deemed a threat to his one-man rule. The lucky ones were sent into exile; others went to prison or worse.

Berdymukhamedov, who took over after Niyazov’s death in 2006, put the names of months back to Gregorian norms while retaining the intense repression. Almost all domestic media is controlled by the state, and access to the internet is severely restricted. According to Human Rights Watch, the regime has employed “forced disappearances” to silence dissidents, providing no information to their families about their fates. Most of the few independent journalists and activists who remain in the country work underground, at constant risk of arrest, while the families of critics living abroad are routinely harassed. Before the emergence of Covid-19, “it was a not-so-open country. But now it’s very, very closed,” says Farid Tukhbatullin, an exiled activist who leads the Vienna-based Turkmen Initiative for Human Rights. “It’s a terrible situation.”

Berdymukhamedov’s nation-building priorities appear to draw equal influence from Stalin and Star Wars. Life for many Turkmens is extremely difficult. The rate of infant mortality is higher than in Bangladesh, and shortages of affordable food are common. The president has nonetheless overseen the renovation of the capital, Ashgabat, into a city of vast, empty boulevards punctuated by otherworldly monuments, including one topped with a golden statue of the president on a charging horse. How much of Turkmenistan’s gas revenue goes to these vanity projects—or to maintaining the lifestyles of Berdymukhamedov and his family, who play a dominant role in the economy—is difficult to pin down. According to Crude Accountability, a Virginia-based group that studies resource policies in the region, the government releases “no reliable information on economic growth, its national budget, oil and gas revenues, or currency reserves.”

Not surprisingly, the Turkmen government is wary of foreign involvement in its most important industry. Only one major Western energy company is active in Turkmenistan: Italy’s Eni SpA, which has a modest operation inland from the Caspian, where Dubai’s Emirates National Oil Co. and the Malaysian state firm Petroliam Nasional Bhd. also produce relatively small quantities of oil that are exported by boat to Russia or Azerbaijan. The largest foreign presence is that of China National Petroleum Corp., primarily in the gas fields in Turkmenistan’s southeast, piping the output for consumption in the world’s most populous country. Overall, energy production is dominated by two state-owned companies, Turkmengaz and Turkmenneft, both controlled by Berdymukhamedov and his entourage. “The hydrocarbon sector is completely under the responsibility of the president,” says Kate Watters, Crude Accountability’s executive director.

One result of this isolation is that changes to environmental standards in the broader energy industry pass Turkmenistan by. Most of the largest oil and gas companies, under pressure from governments to reduce emissions, say they’re at least trying to gain better control of their methane output. Members of the Oil & Gas Climate Initiative, a group of large producers that includes Exxon Mobil, Royal Dutch Shell, and Chevron, have pledged to reduce their “methane intensity,” or emissions per unit of production, by one-third in aggregated upstream operations by 2025. Methane reductions will also be on the table at the international climate talks known as COP26 that kick off in Scotland at the end of October, ahead of which more than two dozen countries have joined a global pact to curb the greenhouse gas. But those pledges mean little in Turkmenistan. Instead, whether the country gets its emissions under control will be largely up to Berdymukhamedov.

The Methane Menace

Read more about the supercharged gas that could turn the tide of global warming.

Kal Sandhu moved to Turkmenistan in 2007. An executive with German oil and gas producer Wintershall, he’d been appointed general manager of its operations in the country, which included some offshore drilling projects that ultimately failed to yield commercially viable finds. Living in Ashgabat was a surreal experience. Foreigners were subject to an 11 p.m. curfew, while businesses were expected to display a portrait of Berdymukhamedov and promptly replace it with the latest officially sanctioned image. At one point, all cars in the capital had to be painted white. “People were fined, or their cars were confiscated until they paid the fines and got their cars painted,” recalls Sandhu, who now works as a consultant in Canada.

The central reality of the Turkmen gas industry, Sandhu learned, was surplus. Landlocked apart from its access to the Caspian—which, with no direct outlet to the oceans, is effectively a lake—the country had little hope of exporting liquefied natural gas by tanker, as Qatar, the U.S., and other energy powers do. Its international pipeline connections were limited, leaving the government dependent on just a few potential customers, all of whom could tap alternative sources of the fuel.

The upshot was that with such vast reserves, Turkmenistan had more gas than it could profitably sell. Some of the resulting choices were unusual. In Ashgabat, gas was so abundant, and the state of central heating so poor, that some residents left their stoves burning all night in the colder months. There was no reason not to.

“It’s like if I was living on Lake Superior and you said, ‘Don’t water your lawn, we need to save some water,’” Sandhu says. A similar logic guided the people running the industry. Turkmen officials, he says, “know for the next 100, 150 years, they have gas. It’s so much.”

This excess supply appears to be one of the fundamental drivers of Turkmenistan’s huge methane footprint. In general, methane escapes into the atmosphere from energy facilities in one of three ways. The trickiest to control are fugitive emissions, a catch-all term for unintended leaks from faulty compressor stations or loose valves. While finding them might require expensive aerial or satellite surveys, the fixes are often relatively cheap and the financial gain from reducing losses might offset the cost, at least when there’s a buyer for the additional gas.

Malfunctioning gas flares are a further source of methane emissions. When gas can’t be pumped into a pipeline—because export facilities are at capacity or a field’s main product is oil, with no outlet for the gas that’s often extracted alongside it—the usual solution is to burn it off.

While not ideal from a climate standpoint, flaring, as the practice is known, has the benefit of turning methane into less potent carbon dioxide. But when a flare breaks down, or fails to combust all the gas feeding into it, the result can be a large release of methane. It’s not just a concern in the developing world: Some of the most consequential malfunctions have occurred in the Permian Basin in the U.S. Southwest.

Venting, or simply letting gas gush unimpeded into the atmosphere when putting it elsewhere is deemed too difficult or costly, is the biggest problem of all. It represents the worst of both worlds. The amount of gas released can be far greater than in fugitive emissions, and its warming potential isn’t mitigated by burning. For those reasons, the practice is drawing tighter scrutiny from regulators in many countries.

Routine flaring and venting have been prohibited in Turkmenistan since at least 1999. But recent research suggests that those restrictions are making little difference. A group of Dutch and Spanish scientists examined methane emissions observed in the country’s western basin from 2017 to 2020, identifying 29 distinct “super-emitters.” Most, they determined, were from unlit flares at facilities operated by either Turkmenneft or Turkmengaz. Some experts have even speculated that, perversely, Turkmenistan’s environmental rules could be contributing to the problem. For a plant manager trying to hide excess methane emissions from his superiors, venting an invisible gas is a more reliable strategy than lighting it on fire.

In October 2020, French utility Engie SA was on the verge of a $7 billion agreement to import liquefied natural gas from the Permian Basin to Europe when President Emmanuel Macron’s government stepped in. Concerned about emissions standards in the Permian, the French state, which owns more than 23% of Engie’s shares, feared that too much methane would be generated in the production of the gas. Soon, the deal was off. Engie would have to find cleaner sources of supply.

Such scrutiny is likely to be a regular feature of gas deals going forward—and potentially a significant catalyst to force the industry to reduce emissions. But for the moment, no one appears to be trying to use similar tactics to shift practices in Turkmenistan.

Unlike production in the Permian, Turkmen gas flows to only one major customer: China. That country is counting on the fuel to shift electricity production away from coal, a transition that began decades ago in Europe and the U.S. Its imports from Turkmenistan are likely to increase, and not just because of economic demands. President Xi Jinping’s government is locked in a bitter geopolitical dispute with Australia, China’s largest supplier of LNG; Turkmenistan is a much more quiescent counterparty, one that’s unlikely to, say, halt shipments during a crisis over Taiwan.

In a July visit to Ashgabat, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi praised Turkmenistan as a “truly reliable strategic partner” and pledged to expand “the volume and scale of natural gas cooperation” between the two countries. Yet despite Xi’s climate-friendly rhetoric, Beijing has so far shown little interest in the methane intensity of its imports from Turkmenistan or anywhere else.

CNPC, the primary Chinese operator in the country, and the National Development and Reform Commission, which oversees China’s economic planning, did not respond to requests to comment for this story.

Some activists are hopeful that China will eventually push Berdymukhamedov to act on emissions. CNPC’s operations in Turkmenistan are concentrated in the eastern part of the country, where it has built new infrastructure that analysts say should be less prone to leaks. But the area is still a global hotspot for methane emissions, according to Kayrros, and Beijing has an incentive to avoid gas being vented uselessly into the atmosphere. For one thing, it’s energy that isn’t going to Chinese consumers or factories, which are struggling with power cuts resulting from insufficient generation.

Emissions at the scale being detected by satellite surveillance in Turkmenistan “represent a very significant loss of value,” says Jonathan Elkind, a former assistant secretary for international affairs in the U.S. Department of Energy. Meanwhile, China itself faces severe risks from climate change, including water shortages in northern provinces and rising sea levels that threaten its coastal cities. If it chose to speak out, Elkind says, “China’s engagement on the methane leaks would be unlikely to be ignored.”

Measures to contain leaks wouldn’t necessarily be expensive and, in some circumstances, could even be profitable. Getting fugitive emissions under control is often a matter of simple fixes closer to the realm of auto mechanics than rocket science: replacing worn-out valves or rebuilding compressor engines. To reduce the need to flare or vent gas, operators need to build more processing, storage, and pipeline capacity—in other words, more of the kind of infrastructure they already have.

The gas captured by such projects can be sold. That’s a big part of why, in the United Nations Environment Programme’s assessment of global methane emissions released this year, researchers estimated that as many as 80% of such abatement projects in the oil and gas sector could be done at little to no cost. While Turkmenistan’s long-standing mismatch between essentially unlimited supplies and scarce buyers make that outcome more difficult, increased shipments to China could change the equation. So, hypothetically, could sales to Europe, provided European Union governments could be convinced the gas was being produced responsibly.

Yet even with those possibilities, a meaningful effort to reduce emissions in Turkmenistan would require Berdymukhamedov’s government to do two things it’s rarely countenanced: come clean with outsiders about the state of its energy sector and accept their help to fix its problems. Given the Turkmen president’s track record, either would be a big ask. “The government has made a deliberate decision not to expose the industry to global forces,” says the University of Glasgow’s Anceschi. “I would be surprised if Turkmenistan does anything that anyone else tells them to do.”

After discovering methane belching from the Korpezhe field, GHGSat executives knew they couldn’t just sit and watch the gas escape from half a world away. “We decided that we needed to see if we can do something about it,” Germain, the company president, recalls.

He soon learned that it wouldn’t be easy. No one responded when GHGSat contacted Turkmengaz. Not sure what else to do, Germain asked the Canadian foreign ministry to see if it could get someone’s attention in Ashgabat. When that failed, he tried some European governments, which didn’t have any luck either. It was only after those two sets of diplomats asked American counterparts for help that Germain received word that the Turkmen government was looking into the problem. Not long afterward, GHGSat’s orbital surveillance revealed some good news: The methane releases at Korpezhe had stopped.

Germain’s team kept checking periodically, looking for any resurgence. For almost a year they saw none. But in early April 2020, the images coming back from space began to look different. Where previously there’d been bare sand, they were suddenly streaked with irregular blotches. Deep in the Turkmen desert, the methane was leaking again. —with Naubet Bisenov and Kathy Chen