The Arctic Revolution That’s Changing Climate Science

Inuit groups spent decades hosting researchers from far away to study the ice and animals. Now they’re taking up the tools and reshaping the science.

In a normal year, November is the month when frozen water reconnects friends and families on Baffin Island in the Canadian Arctic. In the Inuktitut language, the word for November—Tusaqtuut—means “time to hear the news.”

In the hamlet of Pond Inlet, each day the sun appears a bit heavier until it barely heaves itself above the horizon, and then it doesn’t appear at all. Through long hours of twilight and then night, the ice stretches, thickens, and hardens, sealing the ocean beneath. A glacial highway emerges, linking a handful of Arctic communities otherwise kept apart by the harsh terrain of mountains and fjords with no roads in between. Virtually every aspect of life—food, clothing, art, and language—exists because of the ice.

But 2021 has been too wet and warm. All through October, Baffin Island languished beneath a heat dome. Children wore spring jackets with their Halloween costumes instead of parkas. The water stayed open around Pond Inlet. By mid-November people still can’t hunt or travel on the ice, and Andrew Arreak can’t go out to measure it.

“Sea ice is coming a little later, and melting a little earlier, each year,” says Arreak, a 37-year-old Inuit scientist with SmartICE, an organization that tracks changes in the ice in 32 communities across Canada’s north. “The conditions are getting unpredictable.”

Science in the Arctic has, until recently, tended to ignore those living on the front lines of change. There’s a predictable pattern. Researchers from the south arrive, wearing bright-colored Gore-Tex. They hire Inuit guides to patrol for polar bears or collect samples. And they leave laden with data that, to locals, is often neither accurate nor meaningful.

Arreak is taking part in a new wave of climate science informed by Inuit knowledge and perspective. Learning how Inuit and other Indigenous peoples relate and respond to environmental change is crucial, as science begins to focus more on adaptation and resilience, instead of merely tracking or predicting destruction.

Pond Inlet, Nunavut

Across the Arctic, warming is taking place at least twice as fast as in the rest of the world; new research suggests it may be four times faster. Glaciers are receding, permafrost is collapsing, and the animals the Inuit hunt are becoming harder to find. The ice that Arreak knew by intuition as a Pond Inlet teenager is growing unfamiliar to him now, its footprint and historical patterns of strength and weakness in flux.

“It’s not just the thickness of the ice, it’s also what type of ice it is, whether it’s imported ice or newly formed ice,” says Arreak, who’s also a hunter.

“Imported” ice can be years older and therefore several times thicker than the ice that develops with the winter freeze. Chunks will float free in summer and travel south across Lancaster Sound, freezing into bunches and attaching to the new ice formations around Pond Inlet, which sits near the eastern entrance to the Northwest Passage. Where the pieces join there are jagged seams of uneven heights that make snowmobile travel treacherous.

Economic development is amplifying the effects of warming. As the ice season shortens, ships are proliferating in the Northwest Passage, further threatening the marine mammals that have long sustained human life here. A proposal to double production at an iron ore mine 176 kilometers (109 miles) southwest of Pond Inlet would further increase the traffic. “Forming of the ice is critical. If the ships keep breaking the ice while it’s forming, that will screw up all of the ice season,” Arreak says. Channels through which the ships travel in late autumn are the first to melt in the spring.

What happens at the top of the world—where ice provides a reflective planetary shield and permafrost acts as a 1,400-gigaton carbon sink—matters to everyone on Earth. But for Arreak and his community, things are changing here and now.

“Inuit are the original Arctic scientists,” says Trevor Bell, a geography professor at Memorial University of Newfoundland, who co-founded SmartICE, which is now an independent Inuit-run operation. “They’ve been there making observations of the ice and the land for centuries to millennia. In their heads, they have the longest records of sea ice changes in the world.”

There’s stuff everywhere in Pond Inlet, nestled between the untouched expanses of tundra, mountains, and water: stacks of lumber and corrugated steel, disused boats and snowmobiles, rusty oil drums and shipping containers. The more “junk” outside a home, the more affluent the family inside is likely to be; the detritus shows that not all their income is being spent on consumables. Nothing is wasted.

Temperatures in the hamlet regularly drop to –30C (–22F) in winter. House doors here are left unlocked, and it’s considered weird to knock. At 11:45 a.m. there’s a rush of pickup trucks, ATVs, and snowmobiles as businesses close and everyone goes home for lunch.

When Shelly Elverum, an anthropologist who lives in Pond Inlet, enters the library at 3 p.m. on the second Thursday in November for a meeting, the fleeting sun has already set. Inside it’s toasty, like most Arctic buildings. Half a dozen residents, most in their 20s, are sitting cross-legged on the floor or sprawled on benches.

The average age in Pond Inlet—or Mittimatalik, as it’s known in Inuktitut—is just 21, and 60% of the roughly 1,600 people in the hamlet are under 30. This is the first generation with mobile phones, reliable access to the internet, and the skills to play an active role in “southern” science. Ikaarvik, which means “bridge,” is a group created to improve the accuracy and relevancy of Arctic research by incorporating Inuit perspectives and, in particular, knowledge from Inuit elders. Arreak was one of its founders. Today its members are discussing grant applications, the need to recruit new members, and a stack of proposals from scientists seeking their input—including a study on microplastics in Arctic waters and research on bowhead whales.

“Youth get together, and they say: ‘If the science were up to us, what are our top 10 priorities that we would want to address?’ ” says Elverum, who works as a facilitator for Ikaarvik, helping the group coordinate its efforts. Then they meet with elders, hunters, and local leaders to “add, subtract, modify, and ultimately come up with a list of what the community feels are priorities.”

As the concept of decolonizing science gains traction in the circumpolar world, members have found themselves in demand. Elverum delivered a remote presentation about the group’s work at COP26, the United Nations climate talks held in Scotland. In the library, the group is considering a half-dozen scientific requests on the table.

Or they would, if the conversation didn’t keep getting derailed by talk about the iron ore mine.

Two types of science projects preoccupy Pond Inlet these days: those looking at climate change and those focused on the enormous mining expansion proposed by Baffinland Iron Mines Corp. When it comes to forecasting the future, it’s not always easy to untangle the two.

Residents say Baffinland’s existing Mary River Mine coats the snow with a layer of red dust, hastening the thaw. Caribou, already discombobulated by climate change, have been pushed off their calving grounds by its open pit, while seal and narwhal, who’ve been fleeing the area’s warming waters, now have to avoid its ships as well.

The expansion, which would at least double annual production to 12 million metric tons of iron ore, would require construction of a 110-kilometer railway and, critically, increase marine traffic and extend the shipping season in the region.

“To date, no significant impacts on the climate, ice formation, flora or fauna as a result of the Mary River Project have been detected,” the company said in a statement. “To Baffinland’s knowledge, no independent studies in or around the mine have concluded that either.”

Concern that a longer, busier shipping season poses risks to Arctic communities is supported by research from the University of Ottawa, which drew upon Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit—traditional knowledge—and Ikaarvik, in its Arctic Corridors and Northern Voices Project.

The scientists trained Ikaarvik members to use satellite analysis to run mapping workshops with Inuit elders, to determine key areas of importance for Inuit hunting and travel to study. “You get better data, because you’ve got a trusted person talking to a community member,” says Jackie Dawson, a professor specializing in climate change at the University of Ottawa who led the project. “I think in 20 years, Canada will have a really strong Inuit research capacity, and Ikaarvik is just playing a huge part in that.”

The study outlines a range of potential consequences for a region that’s home to a 22,000-square-kilometer national park and a 108,000-square-kilometer marine conservation area, including ice and habitat damage that could jeopardize local communities’ ability to hunt and travel.

In its statement, Baffinland said the recommendations in the report “have been integrated into our operations, including speed limits, no-go zones, no-anchoring zones, and no-icebreaking zones.” The company also said it limits ship traffic when ice is decaying in the spring and forming in the fall.

Four public hearings into the Mary River proposal have been held by the Nunavut Impact Review Board over the past three years, including one the week before the library meeting. The board is expected to issue its recommendation this spring, after which the federal government has three to six months to reach a decision. If the project is approved, construction could start shortly after, unless opponents seek, and win, a judicial review.

The consensus in the library today seems to be that Inuit involvement has been a colossal waste of time. There were at least a dozen Pond Inlet residents who wanted to speak at the last hearing who weren’t allowed, says Jonathan Pitseolak, 22. Those who did weren’t given enough time. “I was ready to pack the boat,” he says. “As the most impacted communities, we have to be listened to. We feel very ignored.”

One of the Inuit who was given an audience at the latest hearing was Elijah Panipakoocho, 77. A respected elder in Pond Inlet, Panipakoocho has witnessed a dizzying amount of change. He grew up in iglu and qarmaq—snow and sod houses—and remembers when Bylot Island’s shrinking glaciers stretched right down to the sea across from Pond Inlet. Hunting was done from dogsleds, and caribou and narwhal were plentiful.

Holding up an aerial photo of a narwhal swimming more than 10 kilometers from a ship, taken from a scientific study, he drew upon Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit to interpret the image. “This is what it looks like when they’re being disturbed,” he said at the hearing, speaking through a translator. “That’s how sensitive the hearing is of the narwhal.”

IQ, as it’s sometimes called, can be difficult for non-Inuit to grasp, for it encompasses centuries of historical observations and experiences and their relevance to Inuit life, language, and culture. It’s like throwing a stone at the ice. While southern researchers focus on the hole it creates, Inuit see the cracks and weaknesses that radiate out from it.

Baffinland’s experts seemed to miss Panipakoocho’s point, says Josh Jones, an oceanographer with the University of California at San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography. He was at the meeting and watched as they thanked Panipakoocho but then reiterated company-commissioned research showing there’s no cause for concern.

Panipakoocho “has been a great source of knowledge to Baffinland over the years,” the company said in its statement. It added that its experts have worked with government scientists to study narwhal behavior. “Narwhal may temporarily respond to a vessel that’s in close proximity … but once the vessel passes, narwhal continue to stay in the area and resume regular behavior.”

Jones, however, was rocked by Panipakoocho’s testimony. His work into the impact of noise on marine mammals, funded in part by the World Wildlife Fund and Oceans North, is meant to provide a counterpoint to similar research by Baffinland Iron Mines. He visits the community a couple of times a year for two- to three-week stretches.

Oceanographers have long suspected narwhal have evolved superior mammalian hearing to navigate dark Arctic waters, but there has been insufficient research to back that up. Panipakoocho’s interpretation of the way narwhal position their bodies suggests they effectively have an extra ear. The whales’ unicornlike spiral tusk, which is loaded with nerves, may be able to gauge acoustic pressure. That would mean researchers ought to be studying the effect of ship noise on narwhal at much greater distances before drawing conclusions about how they’ll react to increased traffic, Jones says. Panipakoocho “taught us about narwhal hearing, and he taught us about how narwhal respond to ships.”

To a non-oceanographer, this might seem like incremental progress. But in the feedback loop of climate change and economic development, the disposition of a narwhal’s tusk may cause larger ripples, Jones says. Scientists know that change accelerates evolution, but it also may be that the ability of a species to cope with rapid change is derailed when there are multiple stressors: It gets squeezed with no room to adapt. If that theory holds, a few extra ships passing through narwhal habitat could have a cascading impact on an already beleaguered population. Panipakoocho’s testimony already has Jones rethinking the equipment he uses for underwater recording; he’s investigating whether even the most subtle mechanical sounds could disturb the whales.

There’s “a broader conversation going on in Arctic science about changing methodologies,” says Stephan Dudeck, an anthropologist and researcher at the University of Lapland’s Arctic Centre who’s worked extensively with Indigenous peoples across Siberia. Understanding the ways in which Indigenous communities build sustainable relationships with the environment offers lessons that can be applied on “a global scale,” he says.

Southerners often like to expound on the vast number of Inuktitut words for snow. A chart on the wall of Arreak’s office illustrates the scientific precision of the language. At least 60 Inuktitut words are required to describe the life cycle of ice. Ilujuq is one of the first stages—when ice crystals form condensation in the air. “If you have eyeglasses and you go inside and they fog up, that’s ilujuq,” he explains.

Arreak is waiting for tuvaruaq: newly formed sea ice that’s safe enough to travel over. As November unwinds, it can’t come fast enough. By the time the sun vanishes and it’s dark all day, Arreak hopes to don sealskin pants and a parka and head out on his snowmobile. Towing an electromagnetic sensor, he’ll measure the thickness of ice as he travels, or stop to install a stationary “smart buoy” to transmit constant real-time data.

Like most Inuit, the father of five has a lot of jobs: In addition to his role as operations lead with SmartICE, Arreak is a search and rescue volunteer and sits on the boards of both the local housing association and the hamlet’s co-op store. He became interested in climate science a decade ago while studying environmental technology through Nunavut Arctic College. Elverum was one of his teachers. Arreak and his graduating cohort came up with the idea for Ikaarvik.

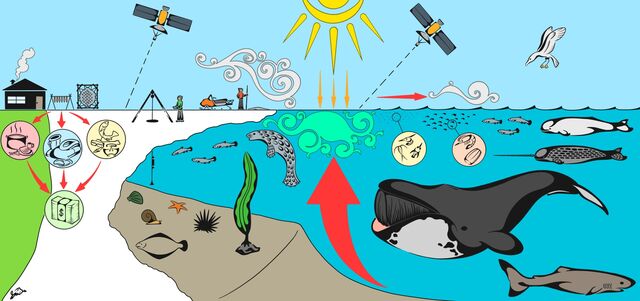

SmartICE is documenting the knowledge of the local community and merging it with scientific data, while it trains Inuit researchers to collect that data and conduct science that directly benefits their communities. Arreak’s research is guided by a committee of residents, including elders, who decide which locations he should prioritize.

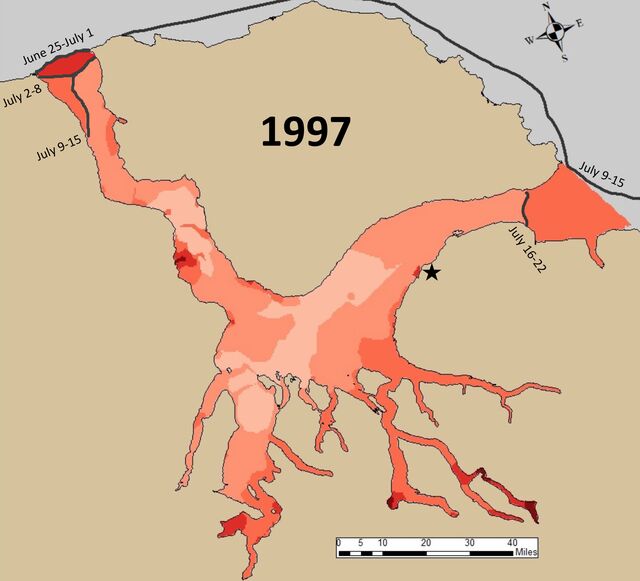

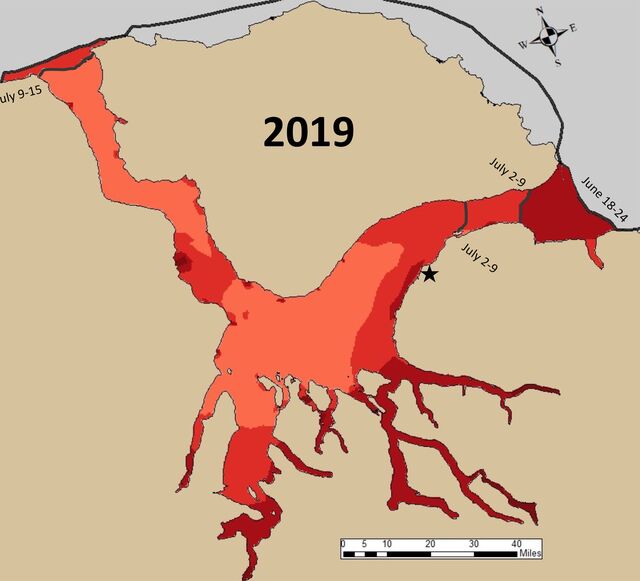

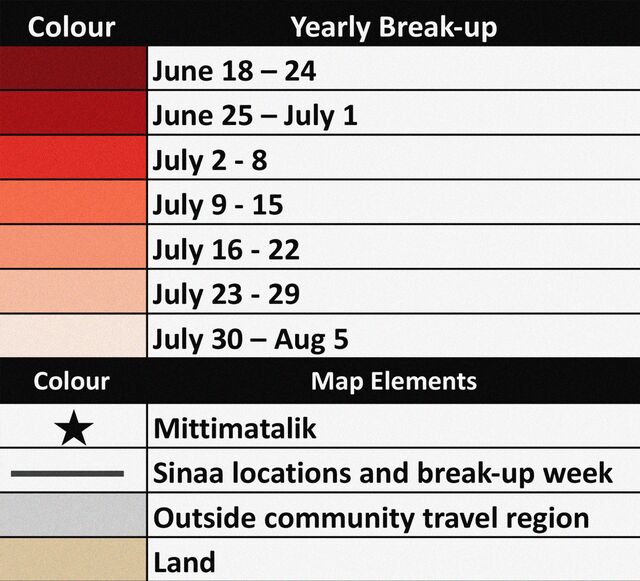

Although he relies primarily on Inuit knowledge to navigate the changing ice, he incorporates modern equipment like his snowmobile sensor to reduce the risks. Back in Pond Inlet he uploads satellite and ground measurements, creating maps with color-coded trails showing where the sea ice is likely to weaken first, and tracking the shifting floe edge (sinaa) where the ice ends and the ocean begins.

A few years ago a hunter fell off the floe edge—it wasn’t where it was supposed to be—and fractured his ribs. Arreak made the four-hour snowmobile trip with a local search and rescue team to treat the man and then used his equipment to find a thick-enough stretch of ice for a rescue plane to land.

The hazards extend beyond the winter. Melting glaciers scatter rock like broken teabags spewing grit, threatening snowmobiles and qamutik, the traditional wooden sleds used to carry supplies. Collapsing permafrost is treacherous year-round, open water is rougher, and skies are windier. “These are all connected,” Panipakoocho says. “These are, at the same time, contributing to the climate change.”

Where the edge of the sea ice meets open water, there’s an upwelling of nutrients that causes Arctic animals to congregate, making it a critical area for Inuit hunters. If the floe edge moves farther away, the cost to hunt, in gasoline and snowmobile repairs, goes up.

Alexandra Anaviapik, 34, sees the impact of multiple stressors on Pond Inlet’s human inhabitants every day. She knows most of the families in the hamlet through her work as the elementary school’s counselor. “In the last 50 to 70 years we went from living off the land to staying put in the community,” she says. “It’s like going from the medieval era to the industrial era in 70 years. Within northern communities, there wasn’t a lot of time to adapt and change.”

Like weak points in ice, stressors send cracks radiating into the community, affecting mental and physical health. Anaviapik cites climate change, economic development, and the global pandemic as the latest external shocks to the psyche of a population still struggling with a devastating colonial legacy. Pond Inlet is already dealing with generational trauma from Canada’s long-running residential school policies, which the nation is only just beginning to fully acknowledge. Over more than a century, the federal government relocated more than 150,000 Indigenous children to often remote boarding schools where abuse was rampant. Thousands died. Entire generations of Pond Inlet residents were torn from their families, including Anaviapik’s father.

Anaviapik and other Ikaarvik women recently participated in a joint Canada-U.K. proposal, with the University of Calgary and University College London, to study the effect of changing sea ice on Inuit livelihoods, focusing on the perspectives of Inuit women. As the floe edge moves, for example, making hunting more difficult, food and sealskin clothing may become scarce, adding to the economic pressure on families. Meanwhile the therapeutic benefit of coming together with other women to exchange patterns and sew will be lost. “It’s a pressure cooker, building up,” Anaviapik says.

There comes a day in the middle of November when, for the first time in a while, even the Inuit say it’s cold: –22C, and it feels like –30. The sun is below the horizon all day now, but without any haze you can still see the mountains and glaciers clearly during the hours of pastel twilight. By mid-December people will finally be able to travel on ice close to land; by January they’ll be venturing farther afield.

Once that happens, Elverum will stand in her living room, watching a line of snowmobile lights disappear over the darkness of Pond Inlet, willing the Inuit hunters to return, after a day or two, with frozen narwhal or seal.

“You’re looking out, watching people struggling against darkness and cold to be able to feed their families, knowing they will have to spend more money, spend more time, go further into the cold and into the darkness,” she says. “And to potentially return empty-handed. It’s painful.”

Arreak will be out on the ice as much as he can. But during this winter, his work will be a little different. For the first time, he’ll be traveling by plane and snowmobile to other Arctic hamlets, teaching Inuit researchers to use his equipment so everyone—Inuit and southern scientists—can pool their knowledge to better adapt. “I try and educate people,” he says. “Climate is changing, and we have to be aware of what we’re doing, so we can enjoy what our grandparents have enjoyed, or our ancestors. Because there’s nothing else like it—being out there.”

But not yet. As the November nights lengthen, Arreak is staying inside with the rest of his community—waiting for the ice.