On Japan’s Front Lines

For millions of Japanese, confrontation between the US and China is already a reality.

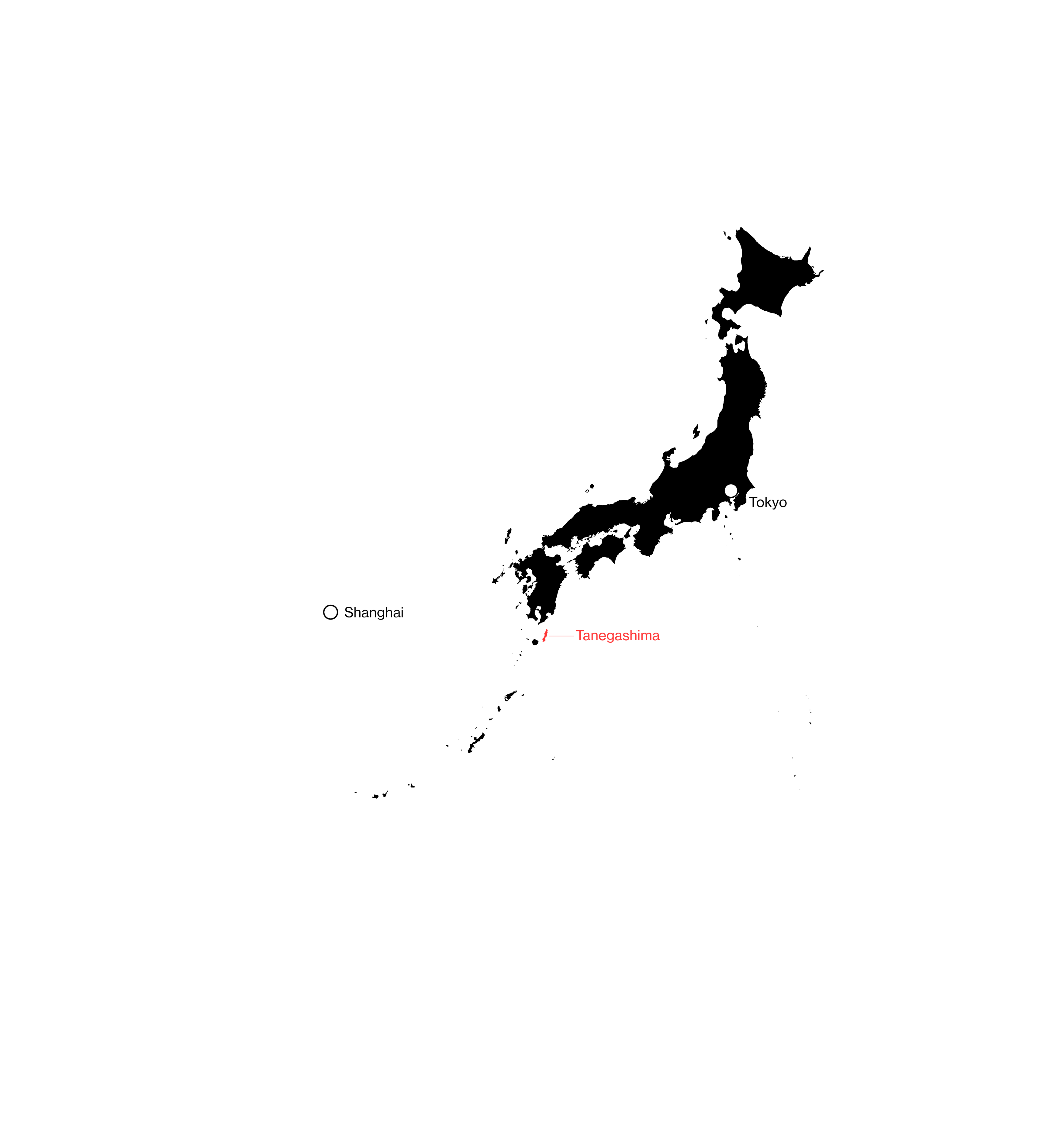

I. Tanegashima 種子島

As the sun rose over Tanegashima, a small island off the southern tip of mainland Japan, a group of amphibious vehicles emerged from the stern of the Kunisaki, a flat-topped assault ship operated by the country’s Self-Defense Forces. The vehicles—essentially floating armored personnel carriers painted in green and brown camouflage, designed to bring an infantry squad ashore under fire—roared through the surf, firing smoke rounds to obscure their positions. Once they hit the beach, which had been fortified with barbed wire and iron posts, teams of soldiers sprinted out the rear doors and fanned out into combat formations. Two hovercraft followed behind; in a real battle they would carry additional troops and armored assets, but for the day’s exercise they were mostly empty. From higher ground more soldiers watched the landings closely, assessing their comrades’ performance in seizing the coastline from an imaginary occupier.

After the drills concluded, Tatsuya Fukuda, a mine warfare commander, briefed a group of journalists who’d been invited to watch. “The importance of this kind of training is obvious if you look at the security environment around our nation,” he said. “It’s unpredictable what will happen when or how. We need to have the power of deterrence to prevent any contingency.” Fukuda didn’t name any specific threats to Japan, but everyone knew what he was talking about. Tanegashima is closer to Shanghai than to Tokyo, in waters that would likely be a key theater in a military engagement between the US and China. Should a war come—an unlikely but increasingly plausible scenario, especially if the battle for Ukraine ignites a new era of global conflict—it might be on the front line.

I visited Tanegashima late last year, part of an extended reporting trip through the chain of islands that stretches in a rough half-circle from southern Japan almost to the tip of Taiwan. My goal was to learn how people there are coping with a dilemma that’s also playing out for Japan as a whole: how to reconcile economic dependence on China, its largest trading partner, with its increasingly hawkish foreign policy, as well as a 70-year security alliance with the US that’s growing tighter than ever.

Like many parts of Japan, the islands have benefited immensely from their relationship with the world’s most populous country, gaining workers, investment, and, before the pandemic closed China’s borders, huge numbers of tourists. At the same time they’re being asked to play a greater security role, hosting a large constellation of Japanese and US forces—often over bitter local objections—that are training to fight their leading economic partner. Collectively the islands represent only a tiny portion of the national population; Okinawa, the prefecture to which many of them belong, has about 1.5 million residents, equivalent to just a couple of districts in Tokyo. But as geopolitical tensions rise their trajectory could have outsize implications for Japan’s future.

Japan’s Tourism

Residents are hotly debating what their stance should be. Arrayed on one side are supporters of the 1947 constitution, imposed by the US military during the postwar occupation, which theoretically forbids participation in armed conflict; they oppose anything that could involve Japan in a future war. On the other are citizens wary of an increasingly assertive China, who fret that Japan will be an inevitable loser if the superpowers clash and it’s unprepared to defend itself. Hanging over these arguments are more workaday concerns: managing the economic impact of a shrinking population; keeping workers and investment flowing, whether from China or elsewhere; and maintaining the quiet, subtropical lifestyle that distinguishes the region from the rest of Japan.

One afternoon, by the slopes of a mountain roughly 25 kilometers (16 miles) away from where the amphibious exercise was held, a group of 17 farmworkers—11 Japanese, 6 Chinese—harvested sweet potatoes together. Stooped over the neatly planted rows, each used scissors to snip the potatoes free one by one, placing them, purple and caked with dirt, into plastic crates for loading onto a truck. At 3 p.m. the crew stopped for a break, splitting by nationality. One of the Chinese workers, Sun Yuanhua, sat on an upturned crate, sipping tea. Sun told me she spends six days a week in the fields, from 7:30 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. She’s been in Japan for more than six years, sending her earnings to her family in Heilongjiang, a poor, bitterly cold province abutting the Russian border. “I make good money,” she said. “I’ve gotten used to life here.” Sun’s boss, farm owner Haruki Nishida, depends on people like her. As in many areas of rural Japan, Tanegashima’s population is decreasing, making it more difficult than ever to find workers. “Without them, I will have to go out of business,” Nishida said of his Chinese employees. “We are at the absolute edge here.”

For decades, claiming to have a plan to develop nearby Mageshima would almost guarantee a skeptical response in Tokyo’s government district. Since the 1970s investors have variously proposed to convert the flat, rocky island into a beach resort, an oil storage facility, and even a landing site for Japan’s never-built space shuttle. None of these ideas went anywhere. Yet eventually officials in Tokyo and Washington decided Mageshima could be useful after all. In the next few years construction crews are supposed to begin turning the island into a significant military base, operated by Japan but also hosting American units.

The plan is important enough to both countries that it was mentioned in the joint statement issued by President Joe Biden and Japan’s then prime minister, Yoshihide Suga, when they met last year. At the very least, Mageshima is intended to be a training hub for US Navy fighter squadrons; it may also serve a similar function for pilots of the more than 100 F-35 stealth fighters Japan is in the process of buying.

Such a purchase would seem to contravene Article 9 of the constitution, which states that “land, sea, and air forces … will never be maintained”—a widely popular provision, viewed by generations of voters as a bulwark against repeating the horrors of World War II. In its original conception, it left responsibility for protecting Japan largely to the US. But successive Japanese governments have argued that Article 9’s language doesn’t prohibit “defensive” systems, using that interpretation to build up a large and well-equipped military, albeit with strict limits on its deployment.

While Mageshima has been uninhabited since 1980, Tanegashima has about 28,000 residents and is just 12km to the east. The commercial district of Nishinoomote, its largest town, is pocked with abandoned storefronts. The people who live there are deeply divided over the military plans. When I visited, signs endorsing both sides of the issue were planted in the soil along country roads, by fences that farmers were using to dry radishes for pickling. “Let’s not be a nation that goes to war; protect constitution Article 9,” read one. “Against the Mageshima base: a quiet island is a treasure,” said another. Elsewhere, someone had advertised their affection for the military: “Welcome: 2021 Self-Defense Forces Drill.”

The most prominent opponent of the planned facility is Nishinoomote’s mayor, Shunsuke Yaita. A former newspaper reporter, Yaita was elected last year by just 144 votes, out of about 10,000 cast, defeating an opponent who advocated for the base. In the bitter campaign, which received national media attention, critics accused the base’s supporters of being willing to sacrifice the local environment—and perhaps to make their sleepy corner of the world a target. The supporters in turn pointed to the economic benefits of security investment. Other Japanese towns have received a range of rewards from the central government in exchange for hosting military installations, from subsidies for students to upgraded public parks, while an influx of soldiers and their families could boost local commerce.

In an interview in Nishinoomote’s modest concrete city hall, Yaita argued that economic gains could never offset the impact of turning Mageshima into a fortress. Free of human interference, the island is home to a population of mageshika, an endangered species of deer, and the surrounding waters are rich with bonito and grouper. They are also believed to contain the remains of Japanese servicemen from the war, giving them spiritual significance for some locals. Mageshima is “not just a deserted island for us,” Yaita said. “Its nature, culture, and historic ruins are so precious.” He acknowledged that China’s assertive foreign policy is raising tensions, but he’s not convinced that Mageshima is the best place to put new military assets. “They don’t need to build it here,” he said.

Part of the reason to do so, in the view of Japanese policymakers, is that the site is less remote from the realities of geopolitics than it used to be. In October a joint Chinese-Russian naval flotilla sailed without warning through the strait that separates Mageshima from Kyushu, the southernmost of Japan’s primary islands. It was the first time armed Chinese and Russian vessels had made the passage together, and given that there are several less provocative ways to cross between the Pacific Ocean and the East China Sea, it sent a transparent message to Tokyo. Local fishermen have also reported near-misses with Chinese-flagged boats, which sometimes veer dangerously close to their vessels despite warnings by the Japanese coast guard. “Everyone wants peace, but we’ve got to respond when others want war,” Sadao Kozuma, a 36-year veteran of the Self-Defense Forces who lives on Tanegashima, told me.

Kozuma, who’s still a reservist, had an active-duty career that straddled two eras of Japanese security policy. When he enlisted in 1978, joining a tank unit, the idea of maintaining any sort of armed force was deeply controversial. Behind his back, he recalled, people would grumble that he was being paid for work that should have been illegal. By the time he retired in 2014, wartime memories had faded, and public opinion shifted to the point that some politicians from the Liberal Democratic Party, which dominates Japanese politics, advocated amending Article 9 to make it less restrictive. Since then, Kozuma argued, the need for Japan to take more responsibility for its security has become acute. “The time will come when we will have to defend our nation by ourselves,” he said.

Under Shinzo Abe, who served as prime minister from 2012 to 2020, as well as his successor, Suga, and the current leader, Fumio Kishida—all of them LDP—the country has taken significant steps in that direction, even though the constitution remains unchanged. The defense budget has risen for 10 consecutive years and will stand at a record 5.4 trillion yen ($41.6 billion) in fiscal 2022; amid the Ukraine war, some politicians are calling for it to increase further.

Japan’s Defense Budget, in Yen

The Self-Defense Forces’ largest vessels, the 248-meter Izumo and Kaga, are being upgraded to accommodate the F-35, making them the first aircraft carriers operated by Japan since World War II. Research is advancing on unmanned fighter jets and long-range missiles, and Japan has joined the recent US-led effort to isolate Russia, breaking from decades of relatively stable relations. Meanwhile, Japanese politicians are inching toward a firmer posture in support of Taiwan. Abe, who remains an influential LDP power broker, told an audience in December that “any armed invasion of Taiwan would present a serious threat to Japan,” and therefore “a crisis for the US-Japan alliance.”

There’s still a deep well of support for pacifism, especially among older Japanese—a critical voting bloc. While I was on Tanegashima, a makeshift stage had been set up in a parking lot adjacent to the local fruit and vegetable market. About 200 people gathered around, beneath a banner that read “No US military facility on Mageshima.” After a series of local activists and politicians took turns at a microphone denouncing the base plan, it was time for Tamiko Shimomura to speak.

The 91-year-old rose slowly from her chair, stooped over a cane. The crowd went silent. “I experienced the war,” Shimomura said. “Air raids hit Tanegashima many times. All the schools were closed. Children were evacuated away. Students were sent to combat zones, over and over.” She continued, her voice strained. “I had three older brothers. One of them, his remains never came home. Even now, they have yet to come home. The other brothers came home only after being interned in the Soviet Union for years. I can never forget how devastated my mother was.” As Shimomura reached the climax of her remarks, she began to raise her voice. “Nothing is as sad and stupid as war,” she nearly shouted. The crowd burst into applause.

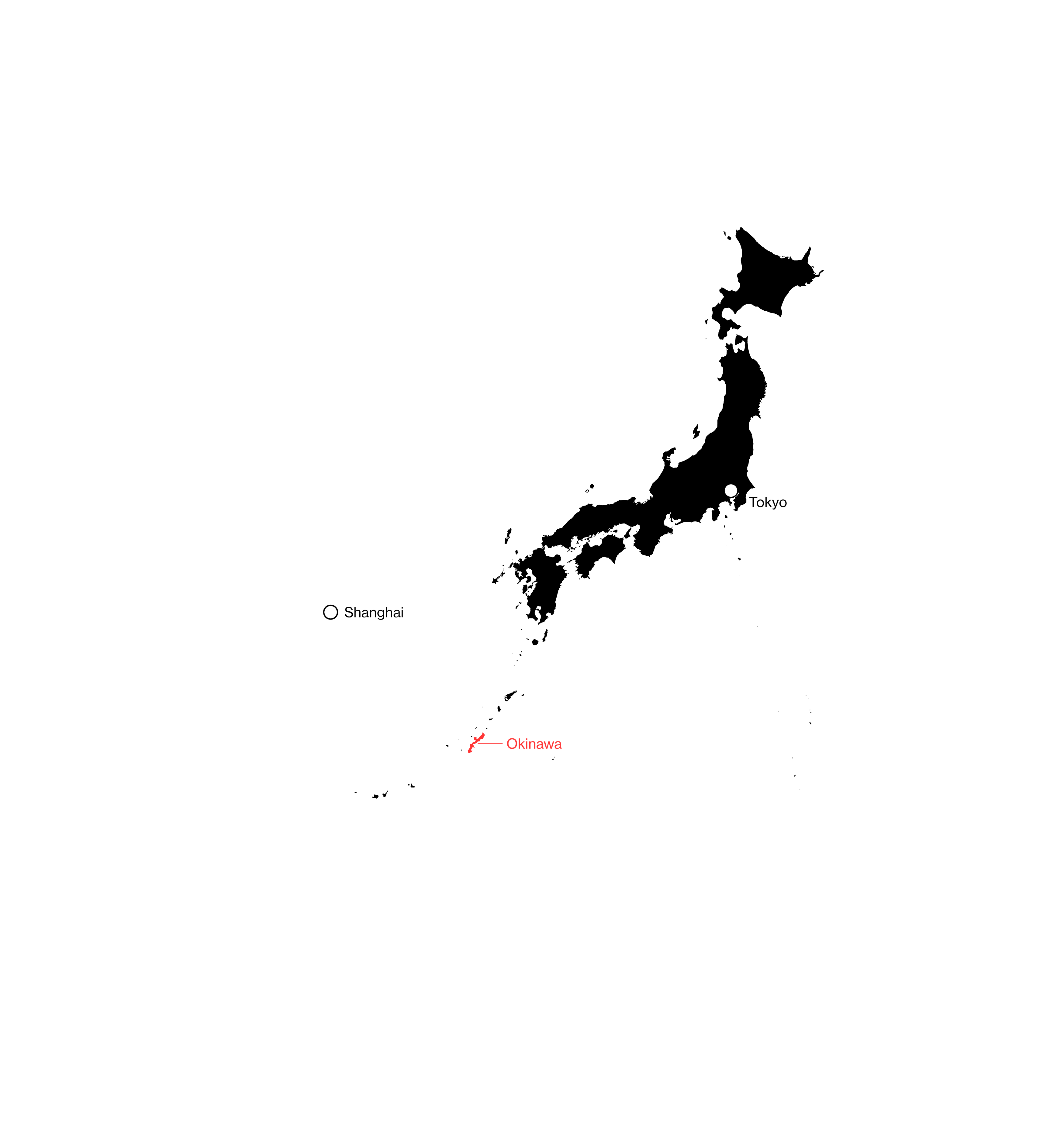

II. Okinawa 沖縄本島

More than 50,000 American military personnel are deployed in Japan, making it by far the most important overseas base for US forces. About 70% of the facilities that host them are concentrated on the narrow, mountainous island of Okinawa—a source of resentment for many Okinawans, who complain they’re shouldering a disproportionate burden. The issue is also linked to grievances over wartime history. During the 1945 Battle of Okinawa the central government forced civilians, including children, to fight battle-hardened US Marines in a doomed attempt to slow the American advance. More than 90,000 were killed, some of them committing suicide to avoid surrender. The island then came under the administrative control of the US military, reverting to Japan only in 1972.

Demonstrations against the American presence have long drawn thousands of residents, and activists hold regular vigils outside bases, singing We Shall Overcome and other protest songs. Their anger stems from such events as the rape in 1995 of a 12-year-old Okinawan girl by three US servicemen, which remains notorious across Japan, as well as the later rape and murder of a local woman by a former Marine. According to government statistics, US personnel have committed about 600 serious crimes in Okinawa since the 1970s, a number that critics maintain is a significant undercount. That record, as well as complaints about noise, pollution, and bar brawls, is a big part of why communities in other parts of Japan view plans for US bases with anxiety. “People say the bases have to be in Okinawa because of China’s threats,” Suzuyo Takazato, a former politician who founded a support center for rape victims, told me. “But we are already exposed to violence—the violence of the US military.”

The most controversial of the Okinawa installations is Futenma, a busy Marine Corps airfield. Carved into sweet potato and sugarcane fields after US troops seized the island during World War II, it was initially intended to serve as a staging ground for the invasion of the rest of Japan. That became unnecessary after the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but the base stayed. As Okinawans rebuilt, Futenma was surrounded by homes and businesses, some just a baseball’s throw from its perimeter fence. Objects occasionally fall from aircraft onto built-up areas, and in 2004 a Marine helicopter crash-landed on the campus of a local college. American and Japanese officials have recognized for decades that operating a major air combat facility in such a dense neighborhood is a problem: The year before the chopper crash, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld called Futenma “the most dangerous base in the world.” Current plans call for its units to be relocated to a new site on the island, far from Okinawa’s main population centers. But the ambitious project has been frustrated by construction delays, as well as years of sit-ins by activists like Takazato. Some analysts are skeptical that it will ever be completed.

It was raining hard as I approached Futenma’s main gate on a November morning, joining a line of cars with plate numbers beginning “Y” or “A,” marking them as belonging to US personnel. At 8 a.m., speakers played an instrumental version of The Star-Spangled Banner, followed by Japan’s national anthem, Kimigayo—a reminder that, although it hosts 3,000 Marines and just 160 or so local staff, Futenma is officially under the jurisdiction of the Japanese government. One of my hosts was Colonel Henry Dolberry Jr., a former attack helicopter pilot who serves as Futenma’s commanding officer. In that role he oversees the operations of an airfield thick with Osprey tilt-rotor transports and hulking Stallion helicopters. He also helps smooth relations with the surrounding community, which can be just as complicated. Later that day one of his colleagues had a visit scheduled with the local mayor, during which he would apologize on behalf of an Osprey crew that had dropped a water bottle over a residential neighborhood.

Taking a seat in a white van, Dolberry escorted me clockwise around the base, passing maintenance hangars and helicopters parked in neat rows along the 9,000-foot runway. I could see tightly packed houses just outside the perimeter fence, so close that their windows vibrate during takeoffs. Dolberry and his colleagues said they try their best to be good neighbors, with personnel volunteering to clean up beaches and help out in English classes.

They also allow Okinawans some access. On the edge of the Futenma property there’s a small farm, where local residents are allowed to grow onions and bitter melons. From the van, Dolberry also pointed out a series of wide stone tombs, dating to before the war. As long as they ask for permission first, families can come to pay their respects to their ancestors. But Dolberry was clear that in his view, the best thing US forces could do for Okinawa, and Japan, was to carry out their primary mission: training for, and hopefully deterring, a future war in Asia. “Whether it be a conflict or competitor anywhere in the region, or far away from the region, we’ve got to be ready to go,” he said.

After we’d been driving for the better part of an hour, Dolberry stopped on a small hill. The rain had softened to a light drizzle, and teams of Marines in camouflage uniforms were working on radar systems nearby. Walking up to higher ground, Dolberry motioned toward the coast, visible in the middle distance. “This is [the] East China Sea,” he said. “The Senkakus”—islets claimed by both Japan and China, a constant source of tension between the countries—are “a couple of hundred miles that way.” Then Dolberry pointed southwest, toward Taiwan, about 600km away. “The great-power competition is occurring right here, today,” he said.

Survey Respondents in Japan With a Favorable Opinion of …

The American presence on Okinawa has also profoundly shaped its economy. About 9,000 civilians work for the US military, making it the second-largest source of jobs after the local government. Thousands more benefit from the money that service personnel and their families spend day to day. Those funds go a long way in one of Japan’s poorest regions, as do the rents, totaling 89 billion yen in fiscal 2020, that municipal governments and landlords receive in exchange for hosting American installations. Some politicians nonetheless argue that Okinawa would be better off without them, allowing it to focus on an alternative business model: attracting tech entrepreneurs and tourists, all of whom would be likely to enjoy the region’s warm weather, white-sand beaches, and excellent food. In this alternative scenario, Okinawa would be a high-tech hub for Asian business rather than an armed camp—a place where US-China tensions and their effects on Japan could be put to one side, if not quite ignored.

In his own way, Zhang Tianyi is trying to live out a version of that future. An engineer from Jilin in northeastern China, he relocated to Okinawa in 2015, taking a job at the local subsidiary of a Chinese software company called Dalian Hi-Think Computer Technology. He was happy to make the move. Zhang had been fascinated by Japanese culture since childhood, delighting in anime and J-Pop songs. “It’s closer to China from Okinawa than from Japan’s main islands, and I feel the same way about the culture,” he told me in polite Japanese. “People are friendly and kind.”

Japan’s International Trade With...

With offices here and in Tokyo, as well as a research lab in Kyoto, Hi-Think has built a substantial Japanese business, even though, according to executive officer Madoka Iha, customers sometimes want to be reassured that their data is safe with a company headquartered in China. In Okinawa, Zhang commutes to a business park built on land reclaimed from the sea and clearly inspired by a Silicon Valley template: wide, straight roads, palm trees, ample parking. Hi-Think’s offices have some 70 employees, about 40 of whom are Chinese. Zhang has come to love Okinawa, spending his weekends visiting verdant mountain parks, where he photographs flowers and butterflies. He owns a Toyota hatchback, which he said he couldn’t have afforded at home, and learning Japanese has allowed him to befriend some of his local colleagues. They never talk about politics. “I’m having a blast,” Zhang said, smiling.

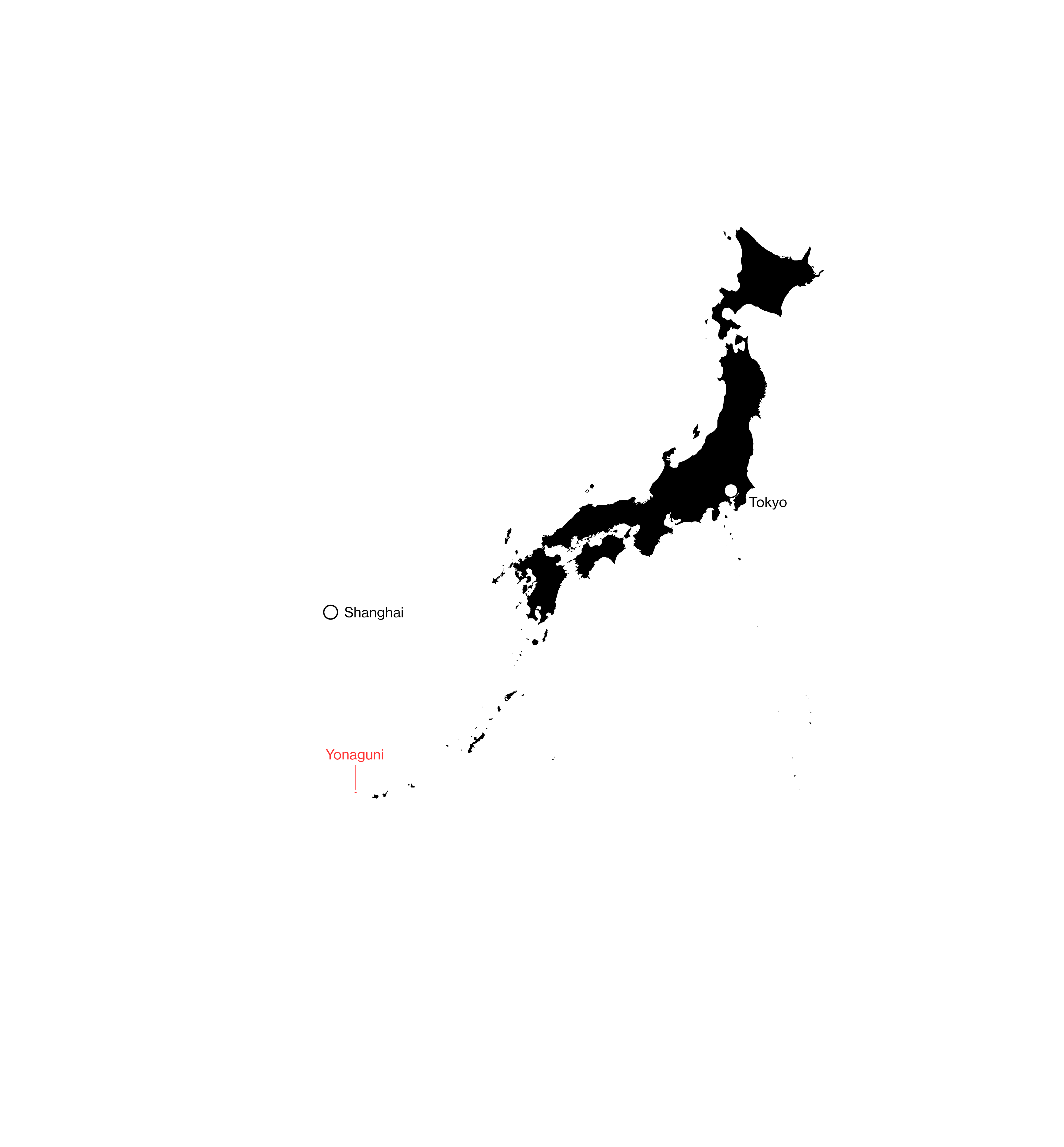

III. Yonaguni 与那国島

My flight to Yonaguni almost didn’t make it. There were gusty winds en route, and the pilot of the 50-seat turboprop told passengers we might need to turn around partway. But he was able to avoid the worst of the weather, and I was soon collecting my luggage at the tiny airport that serves the westernmost landmass in Japan.

It’s an idyllic place. Diminutive “Yonaguni horses,” a cherished local symbol, amble across the roads. The main industries are sugarcane farming and fishing, both by local full-timers and tourists, who come in search of giant marlin. At 8 a.m. each morning the local government plays It’s a Small World After All from speakers dotted around the island, which has about 1,700 permanent inhabitants.

Over the past several years, however, Yonaguni has hosted hundreds of new arrivals, some of whom can be seen taking punishing jogs along the coast in the evenings. The mission of Ground Self-Defense Force Camp Yonaguni, a clutch of low beige structures on the southwestern shore, is officially secret. But it’s not hard to guess what the intelligence and surveillance unit that operates from the facility is up to. Yonaguni is just over 100km from the northern edge of Taiwan, so close that it’s visible on clear days. The island is thus the best place in Japan for observing China’s attempts to pressure the government in Taipei, which include sending large groups of aircraft to probe its defenses.

When discussions about building a base on Yonaguni began around 2008, local opinion was mixed, with opponents raising many of the same concerns I heard about in Tanegashima: noise and disruption, certainly, but also fears about being drawn into a conflict. At the time, the island was so peaceful that its only firearms were two pistols kept by the police. One town meeting devolved into a shouting match. The debate “completely shattered camaraderie and relationships,” said Fumie Kano, who runs a local inn and joined a group of women fighting the plan.

Eventually the local government held a referendum, with 632 people voting to support the base and 445 voting against. Passions have cooled since then, in part because it touched off a minor construction boom and came with funds that paid for school lunches and a new municipal incinerator. Soldiers and their families are helping keep businesses going. “Only good things,” Kenichi Itokazu, Yonaguni’s mayor, told me. “Before they came we were in a dire situation.”

At the same time, some residents’ perceptions have changed in fundamental ways. Kotaro Kobari, a 59-year-old fisherman, moved to Yonaguni about 15 years ago, drawn by its rich stocks of marine life. In an interview by the docks in Kubura, the island’s main port, he said his normal routes once included trips to the Senkakus, about 150km to the northeast. But as with its claims in the South China Sea, Beijing has become increasingly assertive in the disputed area in recent years, sending armed vessels to patrol what Japan considers its territorial waters.

Around 2017, Kobari stopped trying to fish there; Chinese ships, some civilian-owned and others operated by the national coast guard, had begun interfering with Japanese fishing crews. He decided the risk of an accident wasn’t worth it. A Chinese patrol cutter and his 45-foot trawler are “like an elephant and an ant,” he explained. “If my boat is rammed, it will shatter into pieces.” He’s concluded that the threat from China is real and growing. “People on shore may not feel it,” Kobari said, “but out on the sea we feel a great sense of urgency.”

One afternoon, I went to meet Isao Maehokama, the head of Yonaguni’s sugarcane-growing cooperative, at the mill where it processes the crop. Maehokama picked me up in the parking lot in a red minivan, and we talked as he drove me around his farm. The paved road soon gave way to loose dirt, framed on either side by rows of tall, leafy cane. December is harvest time, and Maehokama was confident of a good crop. From his perspective that was a mixed blessing, since it meant he would have to find more workers to get it to the mill. Labor shortages are a constant concern in Yonaguni. There’s no high school, and students leave at 15 to continue their education on larger islands. Many never come back. Three of Maehokama’s four siblings live elsewhere, as do all four of his children. “We need more hands,” he said. “For farming and everything else, we don’t have people who will succeed us.”

As we drove, some metal towers built by the Self-Defense Forces came into view. Maehokama opposed the Yonaguni camp but has come to accept its presence, even as he worries about the longer-term effects. After an initial wave of construction brought more people to the island, the population is declining again; too many old people are dying, and too many young people want to leave. Self-Defense Forces personnel and their families account for an ever-greater share of residents, and Maehokama worries that the community of farmers and fishermen where he grew up is transforming into a military settlement. “That makes me sad more than anything,” he said.

We kept going, Maehokama slowing his minivan to avoid some horses on the road. There was a rice field nearby, idled by a lack of workers. Maehokama wondered aloud if Yonaguni’s residents would have fought harder against the base if there weren’t so few of them left. “It all comes down to depopulation,” he said. Instead, “you rely on others. It’s the easiest thing to do.”

After about an hour and half, Maehokama dropped me off at the sugar mill. It’s been struggling to find enough staff to process the winter harvest, he explained. A few years ago it started bringing in seasonal workers from other parts of Asia. Some are Vietnamese, others are from Cambodia. So far, only one is Chinese.