Jungle Train

Mexico’s AMLO is staking his presidential legacy on a highly contested 965-mile rail route in the Yucatán.

The clear-cut through the forest in Mexico’s southeast is long (the section shown above will be 121 kilometers, about 75 miles), 40 meters (131 feet) wide, and as straight as modern engineering can make it. It’s the right of way for a train—the Maya Train, or Tren Maya, which will run for 1,554 kilometers and connect five states in the Yucatán Peninsula. This is arguably President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s most ambitious infrastructure project, and he’s vowed, repeatedly, to have it ready by the end of next year.

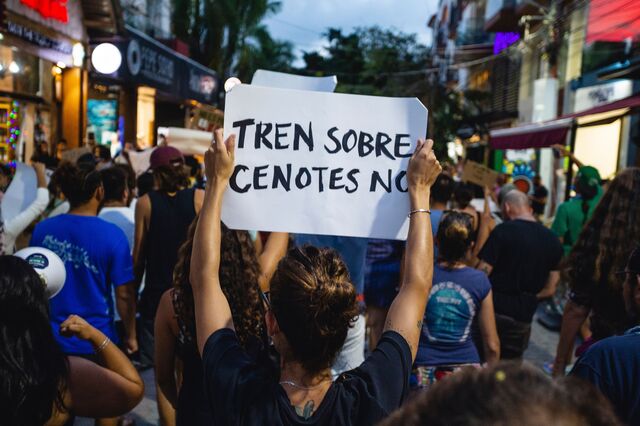

The project is running up against construction challenges, cost overruns, environmental lawsuits, street protests, and supply-chain shortages. With less than two years to go before this self-imposed deadline, the train has become AMLO’s white whale. In the best-case scenario, it will end up costing taxpayers billions more than was planned. In the worst, it could collapse into the Earth.

The train route has seven distinct sections, being built simultaneously. The idea is to develop the small towns where the train will stop and give tourists a simpler way to travel between magnet destinations such as Cancún and Tulum and lesser known gems like Campeche and Izamal. AMLO describes it as transformative—as he’s pointed out, big industrial investments rarely make their way to this part of the country. (He himself is from nearby Tabasco state.) Polls show that a majority of Mexicans approve of the train, and many critics of AMLO’s plan acknowledge the benefits of a rail line in the Yucatán. Just not this rail line, built this way.

Old railways dating to the 1950s cover about half the route, and they’re being overhauled to handle modern rolling stock. To lay track along the rest of the route, construction crews are tearing through rainforest that’s home to hundreds of endangered jaguars, as well as pumas, ocelots, and armadillos.

The route between Cancún and Tulum, Section 5, is proving the trickiest. The train will run atop a system of underground caves, rivers, and cenotes—beautiful water-filled caverns partially open to the sky. The tracks are being laid on the roof of this underground world. Experts say that in places it might not be strong enough to survive the weight and vibration.

The president will have none of it, and his bulldozers are powering through.

AT ALL COSTS

Austerity has been AMLO’s guiding principle as president, except when it comes to two projects he sees as his legacy: Tren Maya and a refinery in the state of Tabasco. The train is now expected to cost about $11.8 billion, an almost 65% increase from the original estimated budget of $7.2 billion. The refinery project is up to $12.5 billion from an original estimate of $8 billion.

A poorly managed pandemic left Mexico with the fifth-highest Covid-19 death toll in the world, and rampant and violent crime is hitting some of the same spots AMLO is looking to connect with the train. Yet every week, the president dedicates a portion of his daily press conferences to Tren Maya, delivering progress reports and insisting the rail line will be inaugurated in December 2023. When asked about any of the issues, challenges, and time concerns facing the project, his response is a variation of the same: The opposition is against his attempts to transform the country.

The opposition, as AMLO sees it, is legislators, biologists, economists—anyone, really—who’ve spoken out against the train, or for that matter any aspect of his administration.

“We’re not dealing with concerns about the route or about the environment,” he said in early April. “It’s not that people love cenotes and fauna. It has to do with money, with political opposition. They’re against us.”

THE ROOF OF THE YUCATÁN

The Yucatán Peninsula has for decades attracted tourists who flock to its white-sand Caribbean beaches, or to visit the archaeological treasures the Mayan culture left behind. The area is also a magnet for scientists looking to study the impact of a meteor that smashed into Earth 65 million years ago, causing the extinction of the dinosaurs.

Even before the asteroid hit, most of the peninsula’s ground was already peculiar and relatively fragile. Geologists estimate as much as 85% of Tren Maya will run through karstic areas. Karst is what becomes of limestone and other kinds of rocks when constant contact with water creates erosion that eventually leads to sinkholes and underground cave systems. That’s why the peninsula is famous for its cenotes. It’s not impossible to build in these conditions, but it takes time, and it takes detailed geological and geophysical studies to know exactly where construction can proceed safely, says Zenón Medina-Cetina, associate professor at the Zachry Department of Civil & Environmental Engineering at Texas A&M University College of Engineering. “One of the greater risks when talking about karst is collapse,” he says. His father, Zenón Medina-Domínguez, the former head of the College of Civil Engineers of Yucatán, agrees: “One can never trust the ground. You have to talk to it, have a dialogue, and let it tell you how it wants to behave. You always have to think about possible failures.”

Collapse is common around the peninsula. The highways that connect Mérida, Cancún, Tulum, and beyond have seen their fair share of large and small sinkholes over the years. The train’s weight and dynamic load will put much more pressure on the ground than cars have ever done, says Medina-Cetina.

AMLO’s administration was widely criticized for beginning construction without detailed studies to determine the train’s economic and technical viability. One government document that analyzed the construction’s environmental impact called for “exhaustive geophysical studies” to determine, with precision, where it’s safe to build. Whether they were done is a mystery.

Bloomberg Businessweek filed requests for information from four different government entities, asking for the contracts awarded to carry out the environmental, geological, and geotechnical studies for the entire route, as well as the studies themselves. Fonatur, the agency in charge of the train project, referred Bloomberg to the already known environmental impact studies for Sections 1, 2, 3, and 4, saying it had no knowledge of other studies. The other ministries responded similarly. Since then, the government has published the environmental impact study for the fifth section.

Ana Esther Ceceña, coordinator of the Latin American Observatory of Geopolitics at National Autonomous University of Mexico’s Institute of Economic Investigations, says there are no more studies. “The clearest confirmation that they didn’t carry out a careful study of the ground is that they keep changing the route every few weeks,” she says. “It’s all so rushed.”

The route for the train has indeed undergone multiple changes. Grassroots campaigns carried out by local indigenous groups and other activists have tangled the project in dozens of lawsuits that have halted construction in various places for stretches of time. Pressed for time, the government gave up on one of them and decided to skip the city of Campeche. The train will now run adjacent to it.

In colonial Mérida, local engineers spent nine months in talks with the government explaining why regular flooding meant it wasn’t a good idea to build the train’s entrance to the town underground. “It wasn’t until Mother Nature came in and showed them,” says Miguel García, who at the time was the head of the College of Civil Engineers of Yucatán. Three tropical storms and two hurricanes battered the city in 2020, proving how hard it would be to build the train underground and keep it from flooding.

Fonatur then explored building an elevated entrance to the train, but that proved too expensive. García says the best option was to build it at ground level. That would have required that some existing overpasses be elevated. The government now says it will complete the entrance sometime in the future. Until then, tourists who want to take the train to Merida will have to drive the final 60 kilometers.

“It’s about just getting it done, foolishly,” Ceceña says, “even if it doesn’t serve its original purpose.”

THROUGH THE RAINFOREST

Mexico’s southeast lays claim to the largest tropical rainforest in Latin America after the Amazon, according to the nonprofit Global Forest Watch. In addition to capturing carbon, the forest is home to hundreds of endangered jaguars and a host of other animals large and small, including the Yucatán parrot.

AMLO pledged emphatically when promoting Tren Maya that the route would go through land that had already been cleared. That has turned out to be false. Anyone driving the train’s route in Section 4—257 kilometers parallel to the highway between Kantunil in Yucatán and Cancún in Quintana Roo—will see the hundreds of miles of thick trees that have been torn up and cut down. Drone footage near the town of Valladolid shows a massive clearing in the rainforest that will presumably be used for one of the train’s stations. AMLO said in March that the government is planting nearly 500 acres of trees along the train’s route to make up for the approximately 247 acres being torn down in the fifth section. In statements to the news website Animal Politico, his office and Fonatur later said they didn't know where or if the trees were being replanted.

“When he says they won’t cut any trees to build this, I get confused, is he speaking metaphorically or is he just living in another world?” says Pedro Uc, a poet and activist who lives in the town of Buctzotz and is part of a group carrying out several lawsuits against the train’s construction.

At a time when threats to tropical rainforests across the world are imminent and scientists point to deforestation as a major cause of climate change, AMLO sees the threat to his project in environmentalists themselves. “We know there’s a political campaign against the train that’s being financed by international organizations and Mexican businessmen and they’re using pseudo environmentalists to carry it out,” he said one recent morning.

NOT IN MY FRONT YARD

Among the many changes the train’s route has undergone, one of the most controversial is in the fifth section, the stretch between Cancún and Tulum. The initial idea was to expand a busy highway that connects Cancún to nearby resort towns in the south and have the train run next to it, much like what is happening in the fourth section. This right of way for the train would have been 17 meters wide.

Local hoteliers wouldn’t have it, saying those 17 meters came too close to their properties. In January, the train was rerouted farther inland. Construction began almost immediately, even though the change meant cutting through almost untouched rainforest and building on top of the cenotes. On May 30, a federal judge halted all work being done from Playa del Carmen to Tulum, citing a lack of adequate environmental studies and the “imminent and irreversible” damage to the area if work continues. Fonatur said construction will continue while it fights the order in court.

“These are superfragile ecosystems,” says biologist and activist Roberto Rojo, who’s also a speleologist, an expert in caves. “These caves will collapse when a train goes above them, and we’ll see the entire area’s water supply affected. The entire region depends on this supply. It really is a source of life.”

“You know that movie Don’t Look Up? Rojo says. “That’s how we feel around here. There are going to be so many problems. They’re risking the viability of their own project, but they just won’t listen.”

THE GHOST OF LÍNEA 12

Infrastructure projects the size and scope of Tren Maya take years to plan and many more to execute. AMLO’s timeline means the train will go from a simple idea to an operational project in a little less than five years.

In September, Rogelio Jiménez Pons, at that time the head of Fonatur, told the newspaper El Financiero about the new cost estimates. He partly blamed the increase on the pandemic, saying Italy and Germany, which were to provide railway sleepers, had closed their borders for lengthy periods. Prices for shipping and raw materials such as steel had also increased steeply, he said. By January, Jiménez Pons was out of the job amid rumors that the president had lost his patience with him. Jiménez Pons declined to comment for this story.

Some critics of Tren Maya say the sense of hurry is worryingly familiar. They’re haunted by the tragedy of Línea 12, a 25-kilometer metro track in Mexico City. Almost from the moment service began in 2012, there were concerns about the quality of the construction; at one point, most stations on the line were closed for almost two years. In May 2021 the track collapsed, killing 26 people and injuring 98. The primary cause was construction errors and poor maintenance, including missing and poorly installed bolts, according to both an official report and the Mexico City prosecutor’s office.

Emiliano Monroy-Ríos, an expert on karst geochemistry and hydrogeology, is a consultant to several companies involved in the construction of Tren Maya. He says people at some of these companies have told him of the pressures they face to deliver updates and to stick to a timeline many consider too strict. (He asked the companies not be named for fear the government will punish them.) “I want to think they’re being careful,” he says, “but that takes more time than they’re being allowed.”

None of the companies with contracts to build Tren Maya agreed to comment for this story or to make executives available for interviews to talk about their progress, studies being carried out, and overall safety of the construction, referring all requests to Fonatur. Fonatur declined several requests for comments and interviews. In April, AMLO said he’d start visiting the Tren Maya route every month to make sure everything is on track. “I only have two and a half years left in my mandate, and I’m just thinking of leaving nothing unfinished, nothing pending,” he said. “I want to retire with a clear conscience that I helped the country transform.”