The Sinking Gold Town

Illegal mining has exploded around the world. One Ecuador town is being consumed by miners' sinkholes.

Deep in the lush forests of southern Ecuador, in a cloud-covered village perched on the western edge of the Andes, a hole opened in the Earth one night late last year.

Small at first, it began to slowly expand and, over the course of an hour that evening, proceeded to swallow huge chunks of cobblestone road in the historic center of Zaruma. Panic spread among residents. They fled their homes—grand, early 19th century structures bathed in tropical pastels—and scurried to safety.

Word of the commotion quickly reached Gladis Gomez.

She was across town with her daughter when the phone rang. The voice on the line was frantic. Gomez’s home was in danger. So too was her elderly father’s, right next door. She hit the gas on her Chevy SUV and muscled it up and down Zaruma’s windy mountain roads as fast as she could.

She arrived to find a neighbor carrying her father out of his home just as the sinkhole was closing in. The three of them ducked into a little market down the street, where they watched on in stunned disbelief as his home wobbled and then, in a flash, plunged deep into the Earth.

“At that point,” Gomez says, “I passed out.”

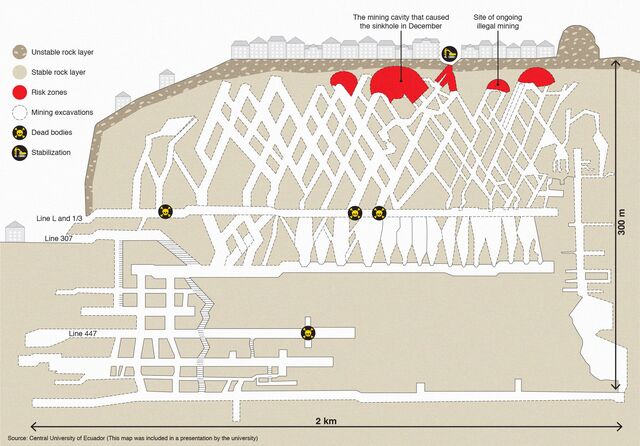

The sinkhole, measuring some 90 feet across and 100 feet down, would consume two other homes that night and leave scores more, including Gomez’s, uninhabitable. It is the product of one thing and one thing only: gold mining. Zaruma is loaded with bullion-rich rock—some of the best in the world—and for over 1,000 years, long before even the Incas arrived, humans have been digging up the Earth to pull it out. There are so many tunnels and branches and offshoots that no one—not even the country’s top engineer on the job, Ivan Nunez—knows where they all go.

But what Nunez, and everyone else in town, does know is this: Ever since the price of gold started to skyrocket early this century, illegal mining has exploded, and as it did, the underground tunnels took on a markedly more precarious feel.

The sableros, or swashbucklers, as they are known to all in Zaruma, pay little attention to structural integrity and lots of attention to tapping into the richest veins around. Even if it means digging right under a school or a hospital or a home. When the sun came up that next day in December, the scope of the problem came into fuller view. The sableros had dug a branch that shot upwards from a horizontal tunnel. The branch came to within 20 feet of Gomez’s house.

Nunez, who’s been tasked with concocting a plan that will end the illegal mining and stabilize the ground under Zaruma, sounds daunted at times by the magnitude of the assignment. “It’s out of control,” he says. Across much of the developing world, authorities offer a similar lament. The value of gold and all sorts of other metals—copper, cobalt, silver, tungsten—is just too high for outlaw miners to pass up, especially after the rally that marked their ascent at the start of the century was supercharged by the easy-money policies that global central bankers have pursued throughout the pandemic.

Miners are wreaking havoc in Mali, Kenya and the Congo, stunting the size of harvests and funding rebel armies. And in South American countries all around Ecuador, they’re razing forests, spilling tons of mercury into Amazon rivers and destroying habitats. The continent’s vast mineral wealth coupled with its extensive organized crime network make it a growing hotbed of such activity. In Zaruma, gangs loosely affiliated with Mexican cartels control some of the mines.

All of this has caught the attention of international authorities.

In April, Interpol released a statement warning about the surge in illegal mining. Six years earlier, it had estimated the industry had reached about $48 billion globally. It hasn’t officially updated those figures yet but noted in its April release that the spike in gold prices and the growing presence of gangs, especially in Latin America, were accelerating the trend.

Gaston Schulmeister, who heads up the Organization of American States’s anti-crime department, calls this combination of forces a “perfect storm.”

“The growth of the illegal mining phenomenon in the region in recent years is clear,” Schulmeister says, “and that growth has occurred in parallel with other organized crime activities such as drug trafficking, smuggling and corruption.”

In Demand

Gold has been on a tear for two decades

Much of this metal slips into global supply chains and ends up in smartphones, televisions and laptops. In places like Zaruma, it happens easily and with little government resistance, the OAS says. Gold-processing outfits buy up illegally mined ore and legally mined ore and dump it onto the same conveyor belt, blending it all up in one big haul that obscures the origin when the bullion is then shipped abroad.

The ore dug up at most mines across the globe only contains tiny amounts of gold—about three to five grams per ton of dirt and rock. This would be typical for a run-of-the-mill commercial mine. Eight grams per ton tips the mine into the high-grade category. Over 30 and it’s a bonanza.

Under Zaruma, there are veins that yield as much as 180 grams a ton and little offshoots of those veins where that number can climb to 500 grams.

These deposits, geologists say, were created by the same tectonic forces that sent the peaks of the Andes shooting miles up into the sky. This was the Early Miocene Epoch, some 20 million years ago, and as the Earth began to shift, it unleashed a torrent of magma that formed massive gold quartz lodes in the rock below.

Mining in Zaruma

A trio of regional tribes—the Paltas, Canaris and Garrochambas—were the first to realize this, historians believe. They settled the area some 1,500 years ago, consensus has it, and began scooping gold nuggets out of river beds.

Around 1480, the Incas rolled in, overpowered the smaller tribes and forced them to mine the metal for them. A few decades later, the Spanish conquistadors did the same to the Incas. After the Spaniards were ousted in the early 19th century, a steady stream of foreign and national ventures began to mine the area, starting with the British-backed Great Zaruma Gold Mining Company. Alexander Hirtz, a geologist and historian who’s been studying the area for decades, estimates more than half of all the gold ever mined in the country—some 300 tons—was pulled out of a twelve-mile-by-fifteen-mile cut of land in Zaruma.

Today, there are scores of small outfits operating on the outskirts of the town. The problem for them is that the ore in those spots is just OK—in the lower end of that three-to-five-gram-per-ton range. Hundreds of years of mining have left few rich lodes.

Except, that is, right smack under the cobblestone roads of Zaruma.

There was long an unwritten understanding, which was codified into law in the early 1990s, that the ground underneath the town itself was off limits to miners. As a result, large pockets of that spectacularly rich ore were left untouched.

Which is where the sableros come in.

They’ve been digging precarious shafts, pathways and coyote holes for decades now. The best of the best rock, they all knew, was up near the surface, and so they slowly inched their way closer to it. But they were always hesitant to get too close. Even for a group comfortable with the ever-present risk of death—several corpses are recovered each year—it was just too dangerous.

Then, a decade ago, one man went for it, and in a big way. Tapping into an old, defunct line that was dug on the outskirts of Zaruma, he and his team blazed a massive tunnel—known to all as L and 1/3—that runs horizontally across the length of the town at a depth of just 400 feet. No other main artery under the town is within hundreds of feet. The sablero, Rommel Coronel, is dead, an early Covid victim in a country that was ravaged by the disease, but local miners estimate he and his crew made a score registering in the hundreds of millions of dollars.

What’s more, Coronel left a major highway that all other sableros, emboldened by his derring-do, could use to stage raids on the upper crust of Zaruma’s subsoil. The map that Nunez and his team are stitching together is a chaotic and seemingly endless maze of tunnels and offshoots. Swiss cheese is the term the locals use to describe the ground.

“This is a huge study,” Nunez says.

Nunez has been in Zaruma full-time for five months now. Other sinkholes had formed in recent years but this one was far bigger, had done far more damage and attracted far more media attention. The town center is a national heritage site, a spot so picturesque the Ecuadorean government has urged the United Nations to add it to the list of world heritage sites.

So President Guillermo Lasso sent in the military to slow down the sableros and sent in Nunez to hatch an engineering fix to the problem. The army failed its job. There are so many secret entryways—chimneys in local parlance—that the sableros kept pouring in non-stop even during the three-month militarization of the area.

Nunez, meanwhile, is still ironing out details of his plan. Seventy-seven and affable with a bushy gray mustache and a broad smile, he bears a certain resemblance to an elderly Gabriel Garcia Marquez. He’s grown accustomed to the scrutiny that comes with high-profile projects. When he got the call to head to Zaruma, he had just finished up a decade-long job in northern Ecuador, where he was fixing flaws in a massive, Chinese-led dam project that has turned into a national scandal.

The scheme he’s landed on is simultaneously simple and extraordinarily complex. His team will drill large wells that will then be packed with cement, rock and sand. This, he figures, will both stabilize the ground and block off the key arteries the sableros depend on. Initial test runs have been encouraging, he says, and he’s begun to expedite them. “We’ve pinpointed where to drill.”

The sablero is waiting on the side of a secluded dirt road in the coffee-growing hills that ring the town.

It’s early one weekday morning in April and the sun is peeking through the dense tropical vegetation that surrounds him. The forest is alive with activity. The birds, frogs and insects are so loud they nearly drown out the sablero as he begins to speak.

He started working in the mines at age 14, he says. Thirty now, he digs for a crew run by a local gang. It’s in cahoots with a legal outfit that lends it rail carts to carry the ore out.

The second of his two daily shifts will begin shortly, and when it does, the sablero will crawl into a small mineshaft just down the road and follow it until it takes him right under the heart of the town. Not far from here, perhaps a mile or so away, is a key entrance that Nunez’s team uses to get into the tunnels.

“It’s a game of cat and mouse,” he says.

Police estimate there are hundreds of sableros working the mines but finding one was an ordeal. There’s an elusive, mysterious element to them. Most locals know one or two but are hesitant to point them out.

When this sablero finally agreed to meet, he did so on the condition his name be kept anonymous. He’s too afraid—of both the gang leaders and of the police—to speak openly. But he is 100% certain that Nunez, and whoever might come after him, are wasting their time. The only thing that could stop the sableros, he says, is if Zaruma were to run out of gold.

“It won’t end,” he says. “That’s the way it is.”

Back in the center of town, Gomez dejectedly agrees with him.

It’s not that Gomez, 55, is against the mining industry. The town, and her family’s homes, were built on gold; her husband Roque works as an engineer at a legal mining company; the owner of the house next to theirs, one of the three that sank into the ground, sells dynamite to miners. Gold is everything here.

It’s the complicity of authorities, local and national, with the sableros that galls her. For years, they could be heard working right under their feet. Explosions would ring out.

"Who could you complain to? Who could you tell? Nobody listened. Nobody paid attention."

(Xavier Vera, the country’s energy and mines minister, says the government is committed to stamping out illegal mining and that the best evidence of this is the way the gangs have targeted him and his team; one aide’s car, he says, was even blown up.)

Night is falling in Zaruma, and Gomez is standing on the edge of the sinkhole, staring blankly down at the dirt and rock that’s been poured on top of the destroyed homes. Her husband’s Toyota SUV was pulled out of the pit a few months ago. It was a mangled mess. “Thank god my father didn’t go into that hole,” Gomez says. “We never would have found him.”

Later, she will walk up the stairs and slip underneath the yellow police tape and give a tour of her condemned home. There are massive cracks in the walls and bags stuffed with debris everywhere. She has no idea when, or even if, she’ll be allowed to move back in.

In the meantime, she and her husband are renting a home across town with her father.

It’s a small, nondescript place that has none of the colonial flair of her house. Just down the street is a defunct elementary school. It lies in ruins, a casualty of the very first sinkhole to open up a few years ago. And it serves as a constant reminder to Gomez of how strange, and perilous, her life in Zaruma has become.