A Century of Lost Wealth

A new Bloomberg podcast investigates a transfer of Native American wealth — and how US policies helped create a modern Oklahoma empire.

Listen to the series here.

Welcome to Osage County, Oklahoma, where every acre and all the oil rights once belonged to the Osage Nation.

More than a century ago, the Osage Nation, whose government had just been dismantled by the US, negotiated a unique arrangement: All the mineral rights to its nearly 1.5 million-acre reservation would be put in a federally managed trust. Those rights soared in value when oil drilling took off in the state in the 1910s, and tales of Osage wealth swept the country — many exaggerated and racist, painting rich Osages as unworthy and financially reckless.

The Osage people were supposed to be safeguarded by the US government because of the agreement their leaders negotiated. Instead, federal policies allowed a massive transfer of Osage land and wealth to outsiders that the Osage Nation is now working to get back.

Some of that wealth was lost during the Reign of Terror, a criminal conspiracy during the 1920s, when White men murdered Osages for their mineral rights. That era is the subject of an upcoming movie directed by Martin Scorsese, based on David Grann’s bestselling book “Killers of the Flower Moon.”

“It was the dominant society's view that these ‘savages’ weren’t entitled to anything, and if they got something, then it was within your right as a White person to take it,” said Jim Gray, a former chief of the Osage Nation and the great-grandson of Henry Roan, who was murdered during the Reign of Terror. “And that mentality spilled out into the entire society.”

But the Osage also lost land and wealth by subtler means, dollar by dollar and acre by acre, for decades. “In Trust,” a new investigative podcast series by Bloomberg News and iHeartMedia, tells the story of how US policies helped facilitate that transfer of riches. It also tells the tale of three brothers who laid the foundation for an Oklahoma ranching dynasty on land once owned by the Osage Nation.

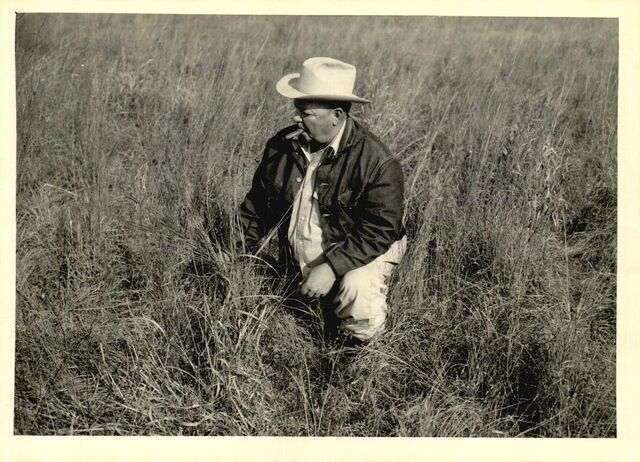

That family, the Drummonds, has deep roots in the state, dating to a Scottish immigrant who moved to the reservation in the 1800s. Today, one member of the extended family is a national TV personality. Another is a rising political power in the state.

If you add up land held by dozens of Drummond entities and individuals, the extended family together makes up nearly 9% of the county. Their sprawling ranches include land purchased decades ago by the three brothers who started Drummond cattle businesses. Tracts owned by all the Drummond family members in Osage County now carry an estimated value of at least $275 million, according to a Bloomberg calculation based on agricultural land transactions and conversations with appraisers familiar with the county.

Descendants say their ancestors purchased their land from both Osage and non-Osage neighbors. At least one member didn’t claim his inheritance, choosing to buy his land from siblings and neighbors instead. Present-day members of the extended family say the Drummonds have had a good relationship with Osage citizens for decades, including during a time when Osage rights were limited by the US government.

Present-day Osage County, Oklahoma

There are still several large Osage landowning families, though none with holdings as large as the Drummonds’. The Osage Nation itself owns 3.5% of the historic reservation.

The lore surrounding the Drummond family’s rise differs dramatically depending on who you ask, but one fact is consistent: The Drummonds bought land, and lots of it. Many of those deals took place at a time when one of the most lucrative businesses in Osage County was making money off wealthy Osages.

All the while, policies by the US government, which owed a fiduciary duty to the Osage people, frequently undercut that promise. Congress capped how much of their own money Osages could access, courts appointed White men to oversee Osage financial affairs, and US politicians undermined Osage leadership. Over generations, this shifted power — and money — from the Osage Nation to White settlers.

Now, as the Osage Nation is seeking to buy back land and the minerals that lie beneath it, the Nation is fighting to reverse the effects of policies that disadvantaged its people for decades — and repair a tattered relationship with the US.

Osage leaders say the trust relationship with the US is one of the better tools available to protect Osage land and sovereignty moving forward, especially given Oklahoma’s efforts to exercise authority on tribal land.

“If you were to take away that trust relationship and not replace it with anything, we would be in a much worse position,” said Jean Dennison, a citizen of the Osage Nation and an Indigenous studies scholar. “It’s been super inconsistent. It’s probably worked against us more than it’s worked for us. But I don’t know that our alternatives were better.”

Listen to episode one “The List” and episode two “The Headright.”