Businessweek

This Is Where Most of the World’s Soccer Balls Come From

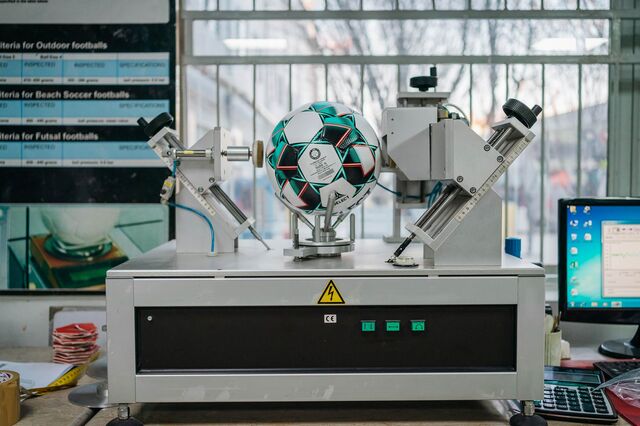

Sialkot, a city in northeast Pakistan, produces about 70% of the world’s supply—including Adidas’s Al Rihla, the official ball of the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar.

Workers collect and examine completed balls at a factory in the small Pakistani town of Sialkot, the soccer ball manufacturing capital of the world.

If you have a soccer ball in your house, there’s a pretty good chance it came from Sialkot, a city in northeast Pakistan near the Kashmiri border. More than two-thirds of the world’s soccer balls are made in one of the town’s 1,000 factories. That includes the Adidas Al Rihla, the official ball of the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar, which kicks off this month.

In Sialkot, about 60,000 people work in the soccer ball manufacturing business—or about 8% of the city’s population. Often they work long hours and sew the balls’ panels together by hand.