|

|

|

Markets choke on QT PieMarkets awoke Wednesday expecting a “dovish hike” from the Federal Reserve. Chairman Jerome Powell thought that’s what he delivered, with policy makers now forecasting only two interest-rate hikes next year, not the three they expected in September. Powell added that the federal funds rate is within the range of estimates of what is considered neutral, which neither stimulates nor constrains the economy. Recall how in early October he caused a stir by saying the rate was still “well below” neutral. Who could be upset by this turn of events? It turns out almost anyone owning U.S. stocks. Meanwhile, anyone who had a long position in bonds did nicely. Bonds were supposed to be in a bear market, and for good reason. The economy is growing, there are reasonable worries about faster inflationthere are reasonable worries about faster inflation and there are enormous concerns about whether the bond market can digest the enormous borrowing by Uncle Sam to finance a bulging budget deficit created by an unfunded tax cut. Ponder also that dovishness means, among other things, that rates will be lower than expected, which also means that bond yields should be lower, all else equal (or ceteris paribus, to put it in the Latin beloved of economists). But all other things were not equal. In response to a question about the Fed’s balance sheet, and the policy of QT, or quantitative tightening, that the Fed has been using to reverse years of QE, or quantitative easing to buy bonds, Powell said this:

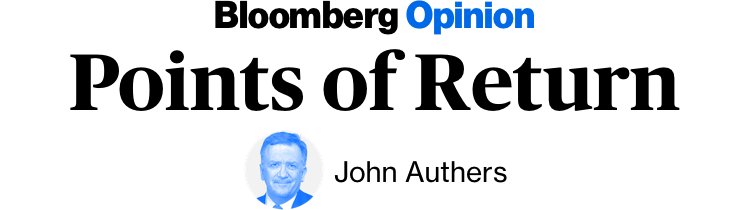

Implicit in this response was Powell’s belief that the steady move to reduce the Fed’s balance sheet assets and, hence, mop up liquidity, was not going to roil the markets. For some reason, he had not said this quite so bluntly before, and judging by the market’s reaction, investors did not think that this was the plan. As a reminder, this is what “automatic pilot” looks like: Automatic Pilot: From QE to QT

Year-on-year change in Fed balance sheet ($000)

Bloomberg Data

We have known for years that QE had helped to keep the stock market aloft, and it was logical to believe that 1) QT would follow QE, and that 2) QT would have the effect of reversing the impact of QE. Wednesday may go down in history as the day when the market finally grasped this. None of this is to say that there was only one cause driving markets today. There were many moving parts, as always. But the Powell comments on QT appeared to be a turning point. Here is a Bloomberg chart of 10-year Treasury yields and the S&P 500, minute by minute, throughout the trading day:

The inverse correlation between the two asset classes was perfect. The first big shock came at 2 p.m. New York time, as the Fed statement was released. That eliminated the slight hope that the Fed might decide not to hike at all. Also, the statement was just barely more dovish than the previous one from the Fed, containing the critical sentence:

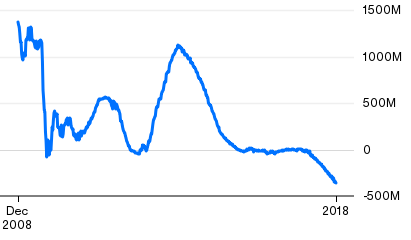

The word “some” was added to the boilerplate language from the previous statement in early November, which could be taken as a sign that the campaign to tighten is nearing an end. However, the generally upbeat message on the economy from the rest of the statement remained unchanged. Many had evidently hoped that the Fed would be getting more nervous and more likely to stop raising rates. As for the accompanying “dot plot” of economic projections, it was more dovish than its predecessor, but still suggested that policy makers fully expected to boost rates two more times next year. This is a screen grab of the projected path of rates, and those of you with access to a Bloomberg terminal can have fun looking at how the Fed’s projections have changed using one of most intuitively named functions: DOTS.

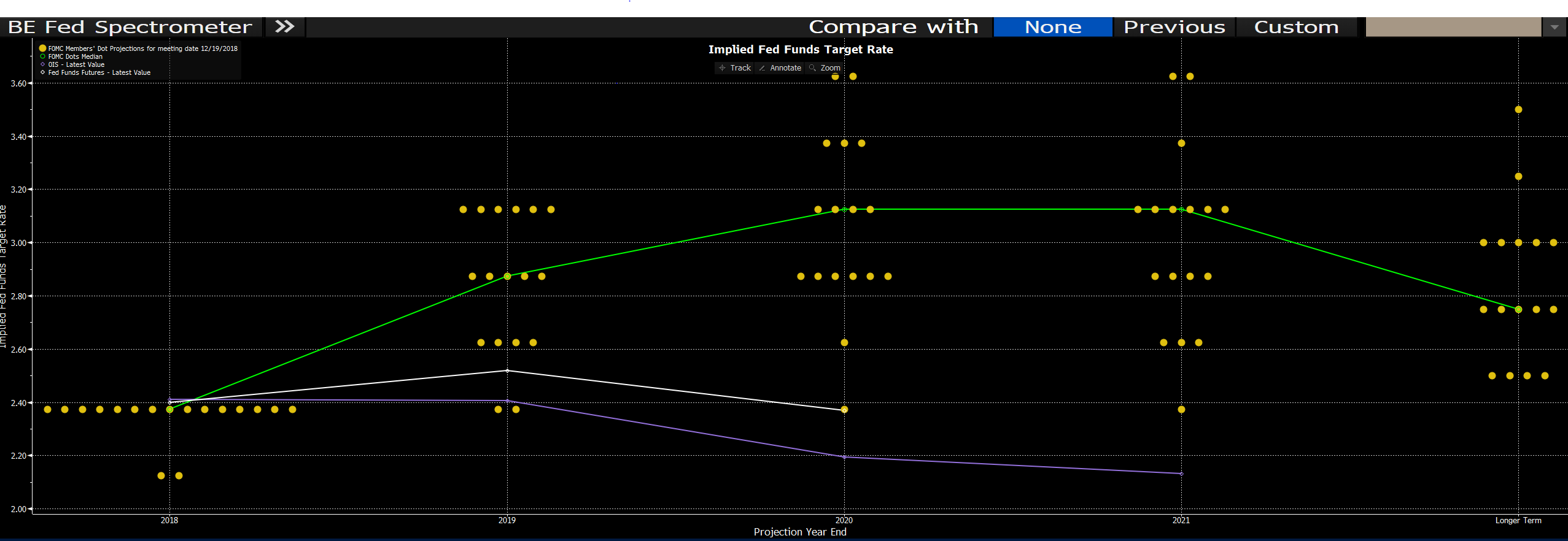

In all, this was a disappointment for a stock market braced for a just-conceivable pause in the hiking cycle, and at least a strong hint that the end of the rate boosts was imminent. I will make some quick observations about what happened. First, bond yields fell sharply even though Powell said he intended to continue with QT on autopilot, which should mean a higher supply of bonds, and therefore lower prices and higher yields. The urge to get out of stocks, still overvalued and still offering profits that some institutions want to bank before they disappear, swamped any urge to get out of bonds as they face a daunting supply surge from both the Fed and the Treasury. The structural factors keeping bond yields low are strong, and yields now appear to be forcing their way downwards. They are now back below the 2.8 percent level that so scared the stock market back in February.

Meanwhile, the yield curve offers no great hope for banks, which traditionally derive much of their profit from the gap between low short-term rates and higher long-term rates. The difference between two- and 10-year Treasury yields is now almost as flat as a pancake. As a flat curve tends to imply a fear that rates will rise in the short run, it could also be taken as a measure of the market’s fear of a hawkish mistake by the Fed:

As for stock markets, I find the drop in the share prices of asset managers breathtaking. Their profits are very much affected by overall returns on the market as a whole, so the collapse in their shares says something about what’s happened to optimism. The sector as a whole has now given up all of its gains since Donald Trump was elected U.S. president in November 2016.

For active managers, there might be a little good news in the fact that as many as 200 of the 500 stocks in the S&P 500 have avoided losses for the year. There’s dispersion and volatility, so managers with skill may have been able to prove their mettle. But the underlying message of the stock market is still emphatically that the Fed is wrong, and that the chances of an imminent downturn are increasing. One good measure of the stock market’s economic outlook is to compare the performance of cyclical and defensive sectors. This is how the industrial sector (cyclical) has fared compared to the utility sector (defensive) since election day:

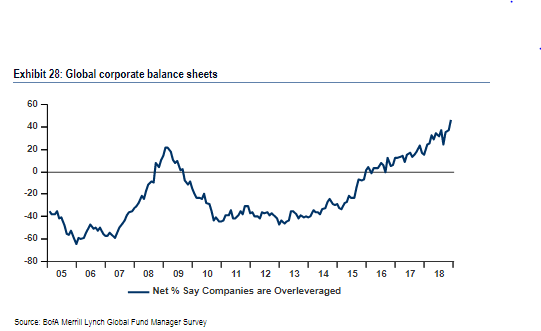

The market and the Fed are at odds. At this point, it’s not clear who deserves to win. Powell seems to have badly misjudged the level of anxiety in markets about QT and the effect it’s having on liquidity. The markets seem to be moving to discount an imminent recession in a far more extreme way than anything in the data currently supports. Sadly, for investors, Powell is not quite the QT they had hoped. Authers notes:Time to capitulate? Bank of America Merrill Lynch published its last global fund manager survey for the year this week. In the light of what has happened in markets this quarter, the level of bearishness revealed by the survey is not surprising. But the pessimism is impressive. The question is whether it has already reached the level of capitulation. On some measures, this does look close to cathartic and irrational fear. The proportion of investors worried by global corporate balance sheets is, astonishingly, even higher than it was during the worst of the credit crisis in 2008:

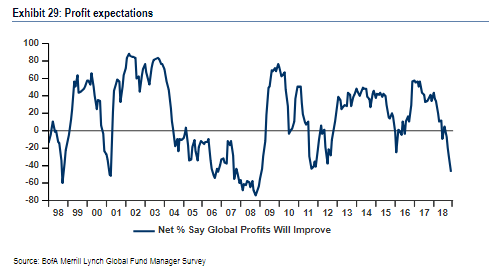

Meanwhile, the outlook for profits has rapidly deteriorated. This number does not look outlandish to me, but the speed with which expectations have fallen strikes me as very strange:

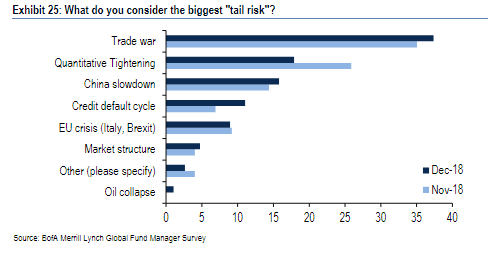

Naturally, given these assumptions, fund managers are shifting away from stocks to bonds and cash, but the allocations are nowhere near cathartic levels. At present, equity allocations are 0.4 standard deviation below the norm, and bond allocations 0.6 standard deviation above. There’s room for these numbers to move much further. To determine how this plays out, look at the survey’s measure of the greatest perceived “tail risks.” Despite the truce announced in Buenos Aires, the trade war between the U.S. and China continues to be the greatest concern. Worries about a China slowdown need to increase, I suspect, before we reach catharsis.

Meanwhile, in Mexico: Nobody was thinking much about what was going on south of the border, but let me just say that Mexico has had a thoroughly predictable “AMLO bounce.” The country’s stock market has outperformed the world as a whole by almost 13 percent since its nadir just before the new president took office. This does not mean that Andrés Manuel López Obrador, a left-wing populist, will continue to produce great returns. He has a lot of work on his hands. But it does show that sentiment had managed to get far too extreme. This is common when western investors witness a success for Latin American populists.

Mr. Market, as much as the new president, created a nice relative buying opportunity. |

|

FOLLOW US |

SEND TO A FRIEND |

| You received this message because you are subscribed to Bloomberg's Points of Return newsletter. |

| Unsubscribe | Bloomberg.com | Contact Us |

| Bloomberg L.P. 731 Lexington, New York, NY, 10022 |